Hello. My name is Varun Indugula, and the name of my presentation is Understanding Racial Disparities in Government Healthcare Spending. Racism, unfortunately, permeates many aspects of our lives, including the healthcare industry. A problem that affects many but is only talked about by a few is racial bias in government healthcare spending, or how governments racially profile areas and dedicate less money to areas with a higher black population. This problem is not well documented in research or literature, which is why this presentation elucidates some patterns seen in government spending for healthcare.

My research connects what kind of healthcare resources a government gives a certain area to the racial makeup of that area. This presentation cites four research articles and some documents published on the topic of healthcare spending and racial biases that influence government decisions. The referenced sources talk about how some healthcare programs, such as Medicaid, disproportionately affect races while also looking into how government actions in an area affect how people are compensated. Essentially, I looked to answer: “How does the racial makeup of a certain area affect that government’s spending for that area’s access to/quality of healthcare, and can a bias be proven?”

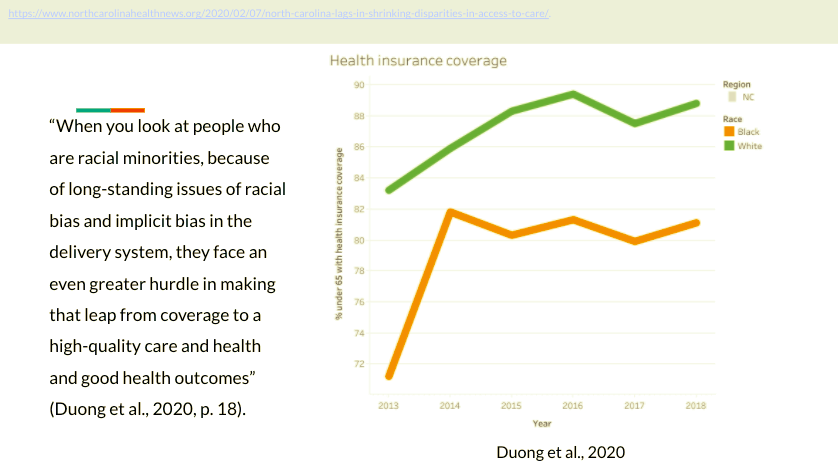

To comprehend the scope of healthcare spending disparities, we can look at the Commonwealth Fund’s report on this issue. We can also use the NC Institute of Medicine’s report: Healthy North Carolina 2030, as explained by Yen Duong to better understand the numerical differences in healthcare quality and access between races (Duong, et al., 2020).

The reports by the Commonwealth Fund, a healthcare policy nonprofit (Jesse et al., 2020), and the report by the NCIOM show that there was general growth in insured percentage rates in NC (Duong, et al., 2020). Although, looking at racial breakdowns of those rates shows that white populations received both easier access to healthcare insurance and higher quality insurance than black people (Healthy North Carolina 2030, 2020). The graph here shows a stark difference between the overall insurance coverage of whites vs blacks, about a 10% difference (Jesse et al., 2020). This shows a quantifiable disparity in the NC healthcare system and it’s up to the people to address it.

The same issue is also a country-wide phenomenon. Two sources looked into problems faced around the nation that reflect this same issue. They focus on Medicaid spending and expansions that states are meant to manage.

Lonnie Snowden and Genevieve Graaf’s journal article “The ‘Undeserving Poor,’ Racial Bias, and Medicaid Coverage of African Americans” from the Journal of Black Psychology talks about how even though Medicaid and the ACA benefitted nondisabled and nonelderly adults, this only occurred in states that accepted Medicaid’s expansions. Black populations have significantly fewer benefits because they reside disproportionately in states that don’t accept Medicaid’s expansive policies (Snowden and Graaf, 2019). Snowden and Graaf describe a psychological phenomenon called “racial resentment” that looks to degrade and belittle other races takes effect in policy and healthcare distribution, most commonly in states that rejected Medicaid’s policies. (Snowden and Graaf, 2019).

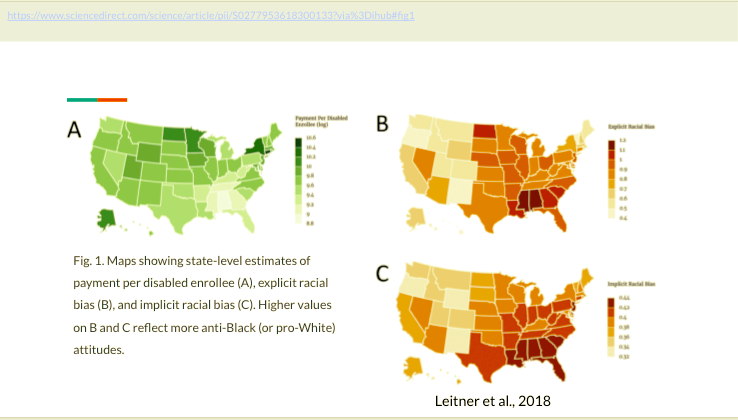

The next source is a specific case study on Medicaid spending for disabled enrollees. Also from Lonnie Snowden, with Jordan Leitner and Eric Hehman, the study compares Medicaid expenditures for disabled people with income levels of whites and blacks, and implicit/explicit racial bias within that state. States with lower white income status had less expenditure for disabled black enrollees (Leitner et al., 2018). These states saw a heightened amount of conservatism, linked to lower spending for black enrollees. They also compiled explicit and implicit instances of racial bias from 1.7 million responses around the country to create levels of racial bias for each state. These levels showed a direct “location-to-spending correlation” where racially-biased states spent less on Medicaid (Leitner et al., 2018). This trend of biased locations spending less is the same that Duong showed in her analysis of the Commonwealth Fund’s report.

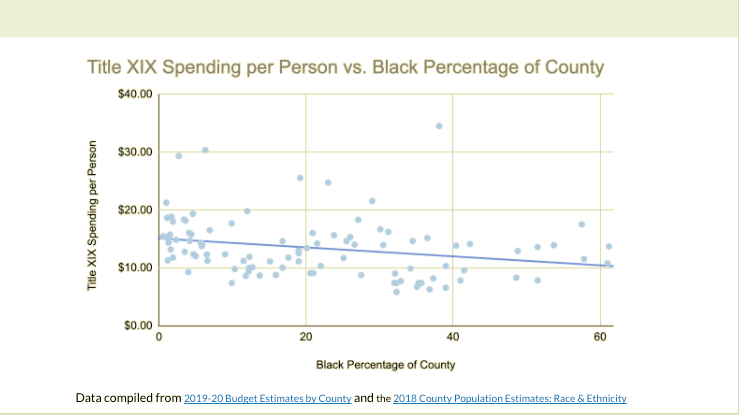

To look deeper into the issue in NC, I compared county-based spending breakdowns for the past year with the racial breakdown of each county to look for correlations in Medicaid spending and black percentage. I looked at two resources to find this correlation. First is the 2019-20 Budget Estimates by County, which provides estimates for NC counties’ spending for that year including estimates for Title XIX Medicaid spending. I also use the 2018 County Population Estimates: Race & Ethnicity. This website, created by the UNC Carolina Population Center, gave me data on counties with the highest black percentage. On my graph, we see the black percentage of a county versus the Title XIX spending per person in that county. There is an obvious downward trend in spending as the black percentage rises. My research, although using statistics from one Medicaid program, emulates the arguments made by Duong’s analysis and Snowden’s findings. The issue of racial healthcare disparities is as immediate as it is dangerous.

Beyond the disparity itself is the acknowledgment of said disparity. While mostly ignored, there was some progress in exploring the issue. An executive order created by Governor Cooper was put in place on June 4th, 2020 to establish a task force to look into racial disparities in the government’s spending habits. Certain sections talk about the need for the task force to eliminate the presence of racial disparities and to look at the unfair response of the government in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic (Exec. Order No. 143, 2020). This task force has yet to report their results but their creation via executive order already signifies a looming issue.

Racial disparities have been an issue that can be seen in all aspects of life. The next step after research is action. As much research as one can do, actions are what truly create change. Once again, I looked to answer whether or not the NC government’s spending habits show a racial bias. My research and the work of many, show that this is true and that the issue spans across the US as well. We must at least acknowledge this issue first, as we work to solve it in the future. Thank you.

References

2018 county population estimates: Race & ethnicity. (2019, December 5). Carolina Demography. https://www.ncdemography.org/2019/12/05/2018-county-population-estimates-race-ethnicity/

Duong, Y., February 7, N. C. H. N., & 2020. (2020, February 7). Access to care inequality in NC persists, study shows—NC Health News. North Carolina Health News. https://www.northcarolinahealthnews.org/2020/02/07/north-carolina-lags-in-shrinking-disparities-in-access-to-care/.

Exec. Order No. 143, 34 NC. Reg. 17 (June 4, 2020).

Jesse, B., Sara, C., David, R., & Susan, H. (2020, January 16). How aca narrowed racial ethnic disparities access to health care | commonwealth fund. Commonwealthfund.Org. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/jan/how-ACA-narrowed-racial-ethnic-disparities-access

Healthy North Carolina 2030 (2020). North Carolina Institute of Medicine. https://nciom.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/HNC-REPORT-FINAL-Spread2.pdf

Leitner, J. B., Hehman, E., & Snowden, L. R. (2018). States higher in racial bias spend less on disabled Medicaid enrollees. Social Science & Medicine, 208, 150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.01.013

NCDHHS: 2019-20 budget estimates by county. (n.d.). Retrieved March 4, 2021, from https://www.ncdhhs.gov/documents/2019-20-budget-estimates-county

Snowden, L., & Graaf, G. (2019). The “Undeserving Poor,” Racial Bias, and Medicaid Coverage of African Americans. Journal of Black Psychology, 45(3), 130–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/095798419844129

Featured Image Source:

Google Images, Creative Commons License