References for Static Slide

Masnick, M. (2011) Age-adjusted obesity rates by U.S. county (2008) [image]. https://www.maxmasnick.com/2011/11/15/obesity_by_county/.

Masnick, M. (2011) Median income by U.S. county (2008) [image]. https://www.maxmasnick.com/2011/11/15/obesity_by_county/.

Hales, C., Carroll, M., Fryar, C., Ogden., C. (2017) Trends in obesity prevalence among adults aged 20 and over (age adjusted) and youth aged 2-19 years: United States, 1999-2000 through 2015-2016. [image]. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db288.pdf.

Presentation Script

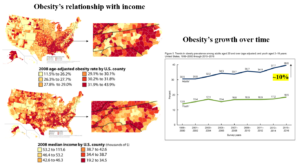

Hello everyone. Today I will be speaking about obesity in North Carolina, specifically with how it relates to low income populations. Obesity is a serious and growing problem in the state. As you can see in the graph on the right, obesity rates have increased greatly from about 30 to 40 percent in the last 20 years. (National, 2016, p. 2; Crawford, 2002, p. 728). Impoverished communities experience disproportionately higher obesity rates, evident in the obesity rate vs median income diagrams shown on the left. (Levine, 2011, p. 2667; Dawson-McClure et al., 2014, p. 152). I am going to discuss why this discrepancy occurs, and what can be done to ameliorate it.

The two main causes of obesity are lack of exercise and excessive/poor food consumption habits. Low income communities experience higher obesity rates compared to other income groups because its members tend to burn fewer calories through lack of physical activity and consume more calories through a poor diet.

The amount of physical activity in low income populations can be diminished due to fewer facilities, like parks and sports fields, and more violence, which discourages exercise outdoors, among other reasons (Ghosh-Dastidar et al., 2014, p. 589; Levine, 2011, p. 2668).

Excessive calorie consumption occurs in low income communities because healthy foods are more expensive and less readily available, so people are more likely to buy processed, unhealthy foods. (Sturm et al., 2011, p. 3; Food, 2018, p. 3; Levine, 2011, p. 2668). Unhealthy foods are very calorie dense yet aren’t filling, thus causing a person to eat a lot of them and consume excessive amounts of calories.

Two general solution strategies to combat obesity include increasing knowledge of the community and improving infrastructure. Educational programs can teach community members how to improve their dietary and exercise behaviors. (Crawford, 2002, p. 728; United, 2021, p. 5). Policy changes can improve diets by subsidizing healthy foods, taxing junk foods, and increasing availability of healthy foods through transportation improvements (Crawford, 2002, p. 728; Dawson-McClure et al., 2014, p. 158). A greater offering of recreational programs and more walkable, safer neighborhoods can increase physical activity levels. (Eat, 2020, p. 2).

Obesity leads to many health costs, which include increased risk of type two diabetes, high blood pressure, stroke, among many other things (United, 2021, p. 5). However, education-oriented and structure-oriented programs, when used in conjunction, have the potential to decrease obesity rates and protect North Carolinians from the negative effects it brings.

Explication of Research

Obesity is a serious and growing problem in North Carolina, not to mention in the United States as a whole. The 2016 CDC state obesity profile found that almost a third of ten million citizens were obese, a dramatic increase of over ten percent in the past two decades (National, 2016, p. 2; Crawford, 2002, p. 728). Impoverished communities, which compose roughly fifteen percent of the North Carolinian population, are especially prone to this disease and experience disproportionately higher obesity rates (Levine, 2011, p. 2667; Dawson-McClure et al., 2014, p. 152). Significant causes of this trend include discrepancies in exercise opportunities and food consumption habits, and the most promising solutions to counteract it will involve simultaneous education programs and infrastructure improvements. Rising obesity rates, especially those in low income communities, must be understood and combatted effectively to lessen obesity’s detrimental effects on personal wellbeing, healthcare costs, and national productivity.

Ultimately, there are countless variables that influence obesity rates in a community, including but not limited to income, education level, race, and sex (Ogden et al., 2017, p. 1370). As a result, the association is very complex. When considering just income level, however, there is a significant relationship between lower income and higher rates of obesity. According to the National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey, the lowest income group experienced almost 10% greater obesity rates compared to the highest income group (Ogden et al., 2017, p. 1370).

Causes of obesity fall into two general categories: lack of exercise and poor/excessive food consumption habits. Food consumption inputs calories, and physical activity (along with maintaining normal body functions) expends them. A combination of too much consumption and too little physical activity leads to weight gain and eventually obesity. Differences in obesity rates between high- and low-income communities can therefore be explained by differences in these two categories. It should be noted that while genes can influence weight gain, obesity cannot be attributed to genetic factors because obesity rates have increased faster than genetic makeup can over time (Crawford, 2002, p. 729).

The amount of physical activity in low income populations can be diminished for multiple reasons. Firstly, more impoverished regions tend to have more violence, which would discourage people from being active outdoors (Ghosh-Dastidar et al., 2014, p. 589). Furthermore, low income neighborhoods typically have fewer parks, public sports facilities, and after school recreational programs—all of which foster exercise—and their residents are less likely to be able to afford gym memberships and sports equipment (Levine, 2011, p. 2668). Lower income jobs can also require long hours, leaving less time to pursue individual exercise. All of these factors contribute to a more sedentary lifestyle, which burns fewer calories and leads to obesity.

The second main cause of obesity, food consumption habits, is even more influential than lack of physical activity. A study found that BMI, a measurement used to determine obesity, is more strongly related to discretionary calories (junk food) consumed than fruit/veggie intake or physical activity levels. In other words, even if a person has a rigorous job and exercises in their free time, they can still become obese because of a poor diet. While lean, healthy foods like grilled chicken, brown rice, and broccoli are low in fat and sugar, high in vitamins, and are filling, highly processed foods like candy, chips, and soda, are low in nutritional value, high in caloric content, and leave you feeling hungry soon after eating them. A diet consisting largely of “junk food” or “empty calories” leads to excessive calorie consumption, which greatly contributes to obesity (Sturm et al., 2011, p. 2).

Food consumption behaviors differ between low- and high-income neighborhoods for multiple reasons. Firstly, price of healthy vs junk foods must be considered. Fresh, healthy foods like milk, meat, fruits, and vegetables tend to cost more, so fewer quantities are consumed in poorer communities (Sturm et al., 2011, p. 3). The availability of healthy foods can also explain obesity rate differences: impoverished regions tend to have fewer supermarkets and thus lack access to fresh food. Over two million North Carolinians, most of which are impoverished, live in “food deserts” such as these, and as such cannot purchase better quality foods even when funds avail (Food, 2018, p. 3; Levine, 2011, p. 2668). Thirdly, marketing within grocery stores contributes to obesity rate differences between income groups. Studies have shown that, compared to high price stores, low price stores had fewer displays to promote healthy foods and allocated more shelf space to junk food (Sturm et al., 2011, p. 5; Ghosh-Dastidar et al., 2014, p. 589). In addition, lower price stores had more displays of junk food, which encourages buying in bulk and, by extension, excessive consumption (Ghosh-Dastidar et al., 2014, p. 589). Since low income families are more likely to shop at low price stores, this factor plays a role in varying obesity rates between income groups.

Because such a wide variety of obesity causes exist, it is hard to pinpoint the perfect solution. With that said, overarching strategies to fight obesity can include increasing awareness and knowledge of the community as well as improving community policies and infrastructure. Educational programs can teach adults how to read food labels, calculate calories and fat, incorporate nutritious foods in their typical meals, and how to incorporate exercise in a busy schedule (Crawford, 2002, p. 728). Additionally, schools can offer healthy living curricula that discourages unhealthy products like soft drinks and promotes healthy eating and staying active (United, 2021, p. 5). These efforts towards greater obesity awareness and education can help a community improve its dietary and exercise behaviors.

Structural, societal changes are also needed to combat obesity in low income communities. Potential policy changes that can improve diets include improving school cafeteria meals, banning competitive foods (attractive, unhealthy options) from schools, subsidizing healthy foods, and taxing junk food (Crawford, 2002, p. 728; Dawson-McClure et al., 2014, p. 158). Raising prices of unhealthy foods to discourage consumption is actually more effective than lowering prices of healthy foods to encourage consumption due to the connection of discretionary calories and excessive calorie intake (Sturm et al., 2011, p. 4). Other potential solutions include improved public transportation and restricted zoning for fast food restaurants, which encourage shopping at healthier food suppliers instead of eating at tempting junk food sources. Exercise among the population can be improved with mandated physical activity increases at school, a greater offering of after school and extracurricular sports programs, and the creation of more walkable, safer neighborhoods and trails (Eat, 2020, p. 2).

Interestingly, both types of obesity prevention strategies have been relatively ineffective in the past when implemented on their own (Crawford, 2002, p. 729; Dawson-McClure et al., 2014, p. 156). Improving the education of a community is only helpful if infrastructure exists for people to utilize—there is no use teaching someone how to eat healthy if they can’t access healthy food to begin with. Similarly, improving infrastructure doesn’t do much good if a community doesn’t know the importance of using it. For example, a study found that substantial changes to school food showed minimal impact in influencing obesity rates, since people opted for other options like vending machines and nearby fast food restaurants (Dawson-McClure et al., 2014, p. 158). When used in conjunction, however, education-oriented and structure-oriented programs have the potential to decrease obesity rates in low income communities and high-income communities alike.

Obesity is a truly concerning problem in our society, both financially and medically. Medical expenses for obese individuals are almost 1500 dollars greater annually compared to those of normal weight (Eat, 2020, p. 3). This phenomenon creates a harmful cycle for impoverished populations: low income situations lead to obesity, which in turn accentuates the low-income problem due to expensive healthcare costs. The health costs of obesity are also daunting: obesity increases the risk of type two diabetes, high blood pressure, stroke, arthritis, sleep apnea, breathing problems, multiple types of cancer, and mental illness; and diminishes overall quality of life (United, 2021, p. 5). Hopefully, widespread, multifaceted solutions to the obesity epidemic will be enacted in the near future to reverse the tide of growing obesity rates in North Carolinians, especially those low-income groups, enabling them to live better lives.

Works Cited

Crawford D. (2002). Population strategies to prevent obesity. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 325(7367), 728–729. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7367.728.

Dawson-McClure, S., Brotman, L. M., Theise, R., Palamar, J. J., Kamboukos, D., Barajas, R. G., & Calzada, E. J. (2014). Early childhood obesity prevention in low-income, urban communities. Journal of prevention & intervention in the community, 42(2), 152–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/10852352.2014.881194.

Eat Smart, Move More North Carolina. (2020). North Carolina’s plan to address overweight and obesity. https://www.eatsmartmovemorenc.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/ESMM-NCPlanToAddressObesity2019.pdf.

Ghosh-Dastidar, B., Cohen, D., Hunter, G., Zenk, S. N., Huang, C., Beckman, R., & Dubowitz, T. (2014). Distance to store, food prices, and obesity in urban food deserts. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 47(5), 587–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.005.

Levine J. A. (2011). Poverty and obesity in the U.S. Diabetes, 60(11), 2667–2668. https://doi.org/10.2337/db11-1118.

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2016). North Carolina state nutrition, physical activity, and obesity profile. https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/state-local-programs/profiles/pdfs/north-carolina-state-profile.pdf

Ogden, C. L., Fakhouri T. H., Carroll M. D., Hales C. M., Fryar C. D., Li X., Freedman D. S. (2017). Prevalence of obesity among adults, by household income and education—United States, 2011-2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(50), 1369-1373. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6650a1.htm.

Sturm, R., Cohen, D. A., Andreyeva, T., Ringel, J. S., Bluthenthal, R. N., Lara, M. … Powell, L. M. (2011). Preventing obesity and its consequences: highlights of RAND health research. RAND Corporation. https://doi.org/10.7249/RB9508.

The Food Trust, The North Carolina Alliance for Health. (2018). Food for every child. The need for healthy food access in North Carolina. http://thefoodtrust.org/uploads/media_items/food-for-every-child-north-carolina.original.pdf

United Health Foundation. (2021). Obesity. In Annual Report. America’s Health Rankings, https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/annual/measure/Obesity/state/NC.

Featured Image Source

Hayes, M. (2013). Before and after pictures of man with 16 months nutrition and exercise changes and losing 180 lbs. [image]. https://depositphotos.com/21010815/stock-photo-weight-loss-success.html