References

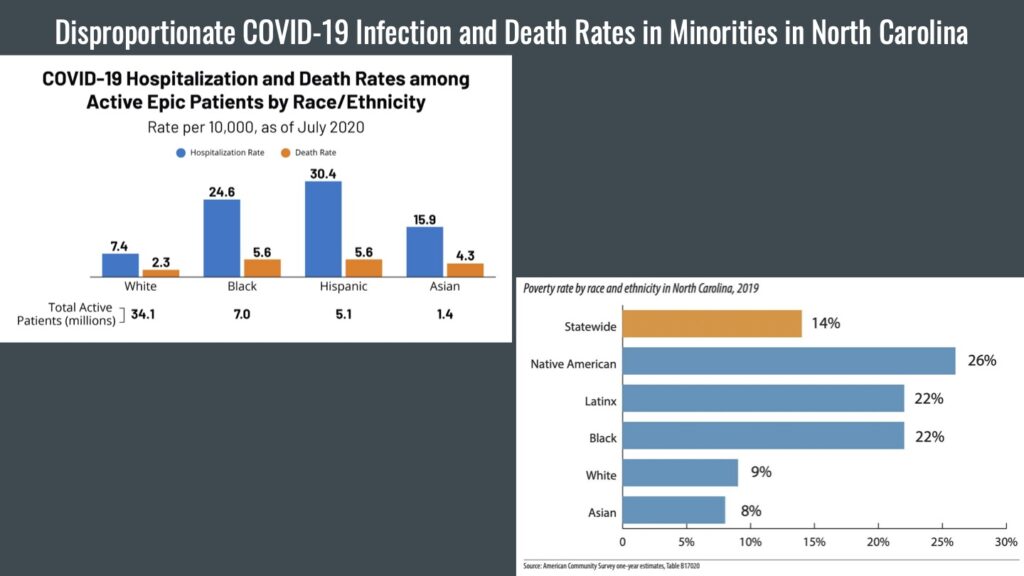

COVID-19 hospitalization and death rates among active epic patients by race/ethnicity. (2020). [Digital image of a bar graph of COVID-19 rates.] Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved October 24, 2021 from https://www.kff.org/report-section/covid-19-racial-disparities-in-testing-infection-hospitalization-and-death-analysis-of-epic-patient-data-issue-brief/.

Poverty rate by race and ethnicity in North Carolina, 2019. (2020). [Digital image of a bar graph of poverty rates in North Carolina.] North Carolina Justice Center. Retrieved October 24, 2021 from https://www.ncjustice.org/publications/2020-poverty-report-persistent-poverty-demands-a-just-recovery-for-north-carolinians/.

Presentation Script:

Hi. My name is Ella King, and today, I’ll be speaking about the disproportionate COVID-19 infection and death rates in North Carolina.

The Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities reports that per one million African American people, there are 1,981 cases of COVID-19, and per one million Hispanic people, there are 947 cases. However, only 658 cases per one million white people were reported (Abedi et al., 2021, p. 740). While some argue that the disproportionate rates reported and demonstrated in the graphic are due to genetics, the root of this disparity is poverty and lack of access to education.

In a recent study conducted by Vida Abedi (2021), higher COVID-19 morality was found in counties with a higher percentage of people under the poverty level (p. 737-738). These counties were found to have more minorities, especially in North Carolina, where one out of five African Americans and Hispanics live in poverty (Harris, 2020, p. 3). This elevated rate contributes to COVID-19 infection in minorities. For instance, “Hispanics were reported to make up 10% of the state’s population but 39% of the state’s COVID-19 cases” due to their inability to afford to stay home from work, which increases their exposure to the disease (Quandt et al., 2020, p. 11).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that counties with more poverty also had a significantly lower percentage of the population with higher education (Abedi et al., 2021, p. 737). In North Carolina, Sara Quandt found that the median years of education for a group of Hispanic families was sixth grade (Quandt et al., 2020, p. 5). This demonstrates that these families have less access to education than the average white family in North Carolina. This lack of access to education makes it harder for minorities to obtain jobs that do not increase their risk of contracting COVID-19.

A potential solution is raising the minimum wage in North Carolina to meet the Living Income Standard. And while further research needs to be conducted on other ways to solve this problem, if some sort of action is not taken, minorities will continue to be more vulnerable to illnesses, like COVID-19.

Explication of Research:

The Johns Hopkins University reported that “as of April 14, 2020, there were over 1.9 million confirmed cases [of COVID-19] around the world with 601,000 cases and 24,129 deaths in the US alone” (Abedi et al., 2021, p. 732). While these cases and deaths consist of people in many different socioeconomic, race, and age groups as shown on the graph, a disproportionate amount of those people have been minorities, especially in North Carolina. Some more heavily associated factors to this issue include genetics, lack of knowledge about the disease, and occupation. However, the root of this disparity in North Carolina is poverty and lack of access to education.

In respect to COVID-19 infection and death rates, the percentage of minorities, specifically the number of African American and Hispanic people, that have been affected is significantly higher than the percentage of white people affected. The Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities reports that per one million African American people, there are 1,981 cases of COVID-19 along with 211 deaths and per one million Hispanic people, there are 947 cases along with eighty-two deaths. Both rates are considerably higher than the 658 cases and seventy-six deaths per one million white people (Abedi et al., 2021, p. 740). African American people also “had 2.6 times the risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection and 4.7 times the risk of being hospitalized,” while Hispanic people, “had 2.8 times higher risk for infection and 4.6 times higher risk for hospitalization from COVID-19” (Seña & Weber, 2021, p. 37). And while it has been argued that these rates arise from differences in genes, they stem from poverty and lack of access to education.

In a recent study conducted by Vida Abedi and her team (2021), higher COVID-19 morality was found in counties with a higher percentage of people under the poverty level (p. 738). And when evaluating their demographics, the “counties with a higher percentage of residents below the poverty level had a higher percentage of [African Americans}” (Abedi et al., 2021, p. 737). One of the main reasons that infection rates are higher in more impoverished areas is that many people held essential worker positions and could not afford to stay home to reduce the risk of contracting the disease. Considering that impoverished areas consist of higher rates of minorities, more African American and Hispanic people are likely to hold these positions. So, while many states put stay-at-home orders in place, data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics revealed “that [only] 19.7% of [African American] and 16.2% of Hispanic workers report being able to work from home,” proving that the majority of these two communities had increased exposure to the disease (Rogers et al., 2020, p. 312).

While the data found in terms of the world depicts disproportionate infection and death rates from COVID-19, the data found for only the state of North Carolina is even more alarming. As the world entered the pandemic, 13.6 percent of people in North Carolina, more than 1.4 million residents, were living in poverty. This is three percentage points higher than the United States poverty rate of 10.5 percent, making the state have the thirteenth-highest poverty rate. With this high poverty rate, it is not shocking that many people in the state hold essential worker positions, increasing their exposure to COVID-19. In North Carolina, one out of five African Americans and Hispanics live in poverty, which correlates to the disproportionate infection rates seen (Harris, 2020, p. 3). For instance, “Hispanics were reported to make up 10% of the state’s population but 39% of the state’s COVID-19 cases” (Quandt et al., 2020, p. 11).

However, poverty does not work alone in contributing to elevated rates of COVID-19 in minorities. In a recent study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, it was reported that “counties with a higher percentage of people below the poverty level had a significantly lower percentage of the population with higher education” (Abedi et al., 2021, p. 737). This pattern can be found in North Carolina communities, especially ones consisting of high percentages of minorities. A study conducted in 2020 evaluated COVID-19 infection in Hispanic families that live in North Carolina. The families were separated into two categories: families with a member holding a farmworker position and families with no farmworkers, called nonfarmworker families. In the study, several farmworker camps were listed as locations of COVID-19 outbreaks by the state Department of Health and Human Services, showing again that essential worker positions, like farming, increase the risk of infection (Quandt et al., 2020, p. 11). But this study was also able to demonstrate that education plays a role in this as well. For instance, the median years of formal education for the respondents in the farmworker families was sixth grade (Quandt et al., 2020, p. 5) and in the nonfarmworker families was eighth grade. This demonstrates that these Hispanic families have significantly less access to education, whereas only thirty-seven percent of white families in North Carolina have households where no adult has a college degree (Tippett, 2018, para. 6). So, it is no coincidence that minorities have elevated rates of COVID-19 death and infection when they have less access to the education that allows them to hold jobs other than essential worker positions.

While the COVID-19 pandemic revealed this issue, it has been present in North Carolina since much before 2019. The observation of disproportionate infection and death rates among minorities can be seen “with the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic where other studies showed evidence of racial and ethnic disparities in the population affected both in exposure, severity, and mortality of the disease” (Abedi et al., 2021, p. 733). This pattern points to larger structural problems within North Carolina as a state that needs to be fixed. One area that is a good starting place for addressing this issue is to decrease the poverty in the state. While one way to do this is to create more jobs, it may be more beneficial to raise the minimum wage. In North Carolina, the “minimum wage is equal to the federal minimum wage at $7.25 per hour, and a full-time minimum-wage job pays just $15,080 annually, far lower than the Living Income Standard” (Harris, 2020, p. 18). Raising the minimum wage would allow for the “1 in 4 families living in poverty in North Carolina, [where] the head of the household or their spouse was working full time” to lift their family out of poverty without working an insane, almost impossible, number of hours (Harris, 2020, p. 18). To raise the minimum wage, the state would have to raise taxes on corporations and upper-class residents. However, this is a small price to pay when it could help prevent children, many of which are minorities, from having to drop out of school and take essential worker positions to help support their families. And while further research needs to be conducted on what the most beneficial approach to solving this problem is and how realistic raising taxes is, if some sort of action is not taken, minorities will continue to be at higher risk of infection and death from illnesses, like COVID-19.

References

Abedi, V., Olulana, O., Avula, V., Chaudhary, D., Khan, A., Shahjouei, S., Li, J., & Zand, R. (2021). Racial, economic, and health inequality and COVID-19 infection in the United States. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 8, 732-742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00833-4

Harris, L. R. (2020, October 29). 2020 poverty report: Persistent poverty demands a just recovery for North Carolinians. North Carolina Justice Center. https://www.ncjustice.org/publications/2020-poverty-report-persistent-poverty-demands-a-just-recovery-for-north-carolinians/

Rogers, T. N., Rogers, C. R., VanSant-Webb, E., Gu, L. Y., Yan, B., & Qeadan, F. (2020). Racial disparities in COVID-19 morality among essential workers in the United States. World Medical & Health Policy, 12(3), 311-327. https://doi-org.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/10.1002/wmh3.358

Seña, A. C., & Weber, D. J. (2021). From health disparities to hotspots to public health strategies: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in North Carolina. North Carolina Medical Journal, 82(1), 37-42. https://doi.org/10.18043/ncm.82.1.37

Tippett, R. (2018, April 12). Obstacles & opportunities for educational attainment in NC. Carolina Demography. https://www.ncdemography.org/2018/04/12/obstacles-opportunities-for-educational-attainment-in-nc/

Quandt, S. A., LaMonto, N. J., Mora, D. C., Talton, J. W., Lauriente, P. J., & Arcury, T. A. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic among Latinx farmworker and nonfarmworker families in North Carolina: Knowledge, risk perceptions, and preventative behaviors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5786. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165786

Featured Image Source:

Google Images, Creative Commons license