References

Hommes, R. E., Borash, A. I., Hartwig, K., & DeGracia, D. (2018). American Sign Language interpreters perceptions of barriers to healthcare communication in deaf and hard of hearing patients. Journal of Community Health, 43(5), 956–961. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-018-0511-3.

Schoenborn, C. A., & Heyman, K. (2015, November 6). Health disparities among adults with hearing loss – 2000-2006. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/hearing00-06/hearing00-06.htm.

[NC DSDHH logo]. (n.d.). https://yt3.ggpht.com/ytc/AKedOLR3zlPZPFvVtIDMP1Xtk7VziriGsXir_EU_KK3k9Q=s900-c-k-c0x00ffffff-no-rj.

Presentation Script:

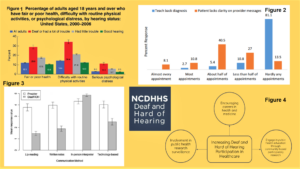

Hello, my name is Baylee Materia, and today I will be discussing “Healthcare Disparities Among the Deaf and Hard of Hearing.” North Carolina’s hearing loss population is rapidly growing (Withers & Speight, 2017, p. 107). With this in mind, the state’s medical community must reexamine its negligent practices that contribute to the significant health disparities this group faces (Figure 1), including higher risks for adverse health outcomes (Peter, May, Paintsil, & Dansan, 2018). Ultimately, my study aims to examine the reasons behind these health disparities and to explore possible solutions that North Carolina can enact.

The main cause of these health disparities is communication barriers that the medical community does not work hard enough to overcome. Studies show that doctors have a limited understanding of this community’s desired communication methods and fail to utilize the “teach-back” method when giving instructions, as seen in figures 2 and 3 (Hommes, Borash, Hartwig, & DeGracia, 2018, p. 958). Doctors also fail to consider the diversity of this community; each individual may have differing needs, and practitioners must be flexible (Withers & Speight, 2017, p. 107). When doctors fail to communicate properly, the results can be confusing and traumatic for patients (Sheppard, 2013, p. 504). Additionally, many doctors view deafness as a disability and focus on treating this rather than the issue at hand, disrespecting the Deaf culture in the process (Sheppard, 2013, p. 504). These negative experiences discourage them from seeking medical care. Communication barriers also lead to low health literacy among this population, resulting in poorer health outcomes. These factors combined give rise to the health disparities observed.

In response, I propose an expansion of training programs by the state’s Division of Services for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing. Currently, this governmental organization holds infrequent educational and empathy-building workshops for medical professionals (Withers & Speight, 2017, p. 109). Holding these more frequently or even making them mandatory could make doctors’ more equipped to communicate with these patients. Furthermore, encouraging Deaf and Hard of Hearing individuals to take more active roles in healthcare through medical careers, public health education, and research surveillance will foster a more accepting and accessible environment (Figure 4) (Barnett, McKee, Smith, & Pearson, 2011, p. 2-3).

To summarize, it is evident that action must be taken as soon as possible to reduce the health disparities plaguing this rapidly growing minority. The solutions I described represent just a few suggestions, and more research is necessary to determine a full course of action. We must call upon our state and the medical community to do their part in serving justice to this underserved group. Thank you for your time, and I will now open the floor to questions.

Explication of Research:

Hearing loss is one of the most prevalent health issues in the state of North Carolina. Studies project a staggering 69% increase in the hearing loss population between 2002 and 2030, making this group represent nearly 1 in 5 members of the state’s entire population (Withers & Speight, 2017, p. 107). With this rapid growth in mind, the state’s medical community must reexamine its negligent practices that contribute to the significant health disparities this group faces, such as a higher risk for adverse outcomes from cardiovascular issues, testicular cancer, and pregnancy (Peter, May, Paintsil, & Dansan, 2018). Ultimately, the goal of this study is to closely examine the reasons behind the health disparities faced by the hearing loss community and to explore possible solutions that the state of North Carolina can enact to minimize them.

Significant communication barriers exist between the Deaf and Hard of Hearing (HOH) and their practitioners. What most would consider a simple check-up becomes a frustrating and laborious process for these patients, and relaying crucial health information to them becomes a challenge. This issue is compounded by many doctors’ failure to overcome such barriers. A 2018 study published in the Journal of Community Health surveyed ASL interpreters to learn about practitioners’ actions when dealing with Deaf and HOH patients. An astonishing 81% of these interpreters reported that doctors rarely utilize the “teach-back” method during their appointments, which involves asking a patient to repeat the doctor’s directions to ensure their full comprehension (Hommes, Borash, Hartwig, & DeGracia, 2018, p. 958). Because this method is so infrequently used, hearing impaired patients — who are typically not empowered to ask for clarification — often leave misinformed and confused about their next steps. Additionally, interpreters also noted the drastic differences between what hearing impaired patients and doctors view as adequate communication accommodations, respectively. They reported practitioners as being much more likely to consider lip reading, written notes, and technology-based methods adequate than patients would (Hommes, Borash, Hartwig, & DeGracia, 2018, p. 958). This reflects the minimal degree of understanding healthcare professionals have about how to best help their Deaf and HOH patients, which is a significant factor in the disparities they face.

Additionally, healthcare professionals often dismiss the diversity present within the Deaf and HOH community. As argued by Jan Withers and Cynthia Speight in their 2017 study, “Hearing loss encompasses a wide range of disability, from those born profoundly deaf, to those with adult-onset mild/moderate hearing loss, to those with various manifestations of both hearing and vision loss” (Withers & Speight, 2017, p. 107). This means that there is no singular solution to the troubles this community faces. While one method of communication, such as a technology-based interpreting system, may be suitable for one patient, it may not be preferred by or accessible for another. Therefore, the full cooperation, compassion, and flexibility of healthcare professionals are necessary when dealing with each individual patient.

Furthermore, the negative experiences that members of this community have in the healthcare world make them less likely to seek treatment when necessary. When the procedures that are being performed are not fully described to the patient, the confusion can quickly lead to lasting trauma. For instance, a 2013 study recounts a Deaf woman’s first pelvic exam and how it felt comparable to an act of sexual assault (Sheppard, 2013, p. 504). This is just one example of the discomfort that Deaf patients report after medical appointments. Additionally, hearing loss patients also cited never being asked about their feelings as another reason why they are hesitant to see a doctor (Sheppard, 2013, p. 508). This lack of sympathy makes them feel uncared for and lessens their likelihood of seeking a second appointment.

Moreover, another factor discouraging Deaf patients from seeking medical help is the overwhelming perception of deafness among medical professionals as a disability rather than a piece of cultural identity. This group “share[s] experiences, insight, humor, theatrical performances, and Deaf historical icons in a way that is unique to their culture” (Sheppard, 2013, p. 504). Members of this community often report their doctors fixating on their deafness and potential treatments for it rather than the true issues at hand, which leaves them feeling disrespected. This is yet another reason why Deaf individuals choose to seek medical care less frequently than they should, which puts them at a greater risk for adverse outcomes.

Deaf and HOH patients consistently show signs of low health literacy. These individuals have a limited access to general health information throughout their lifetimes. This is caused by a combination of barriers, such as the inability to overhear doctors’ discussions and the poor accessibility of health information (Barnett, Mckee, Smith, & Pearson, 2011, p. 1). Health illiteracy is associated with less frequent medical appointments, poor adherence to medical advice, and less ideal outcomes for chronic diseases. For example, many Deaf and HOH individuals are unaware of their family medical histories. This is important knowledge, because risk for certain diseases is linked to genetics. If one is unaware that they are at a high risk, they will not seek preemptive treatment and may suffer greater consequences in the long run. This is just one example of the ways in which health illiteracy contributes to the health disparities observed.

Considering these established factors, there are multiple ways in which the state of North Carolina can attempt to address the health disparities affecting this community. Currently, the state’s Division of Services for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing (DSDHH) works to deliver useful information and accommodations to the hearing loss community. They also run multiple training programs for healthcare professionals, including one that puts them in the shoes of a deaf patient to build empathy and understanding (Withers & Speight, 2017, p. 109). Those who have participated in such programs overwhelmingly describe them as “enlightening” experiences (Parsons, 2019). To further improve healthcare conditions for this population, such interactive programs should be expanded and held more frequently throughout North Carolina. These educational and enlightening courses can make a large difference in the way doctors treat their Deaf and HOH patients. While they are currently conducted on a small, occasional scale, making these workshops more readily available or even required can facilitate great strides in the fight towards a more Deaf-inclusive healthcare system.

Moreover, another method of combating health disparities for this community is to strengthen Deaf and HOH participation within the health field. This will be a three-pronged process that includes encouraging young Deaf and HOH students to pursue careers in medicine, encouraging ASL users’ participation in public health, and including the Deaf and HOH in public health research (Barnett, McKee, Smith, & Pearson, 2011, p. 2-3). The first prong involves expanding pipeline programs for health careers to include Deaf and HOH youth and extending pre-health mentoring to them. This can be accomplished through social programs sponsored by the state’s DSDHH. The second prong may involve community-based participatory research (CBPR), which would allow ASL users to enrich the public health curricula with information about the Deaf community. Finally, the third prong would involve the inclusion of Deaf and HOH individuals in the revision of recruitment and consent processes for health research studies in order to make them more accessible. Overall, boosting the hearing loss presence within the health sphere will foster a more accessible and comforting environment with which members of this community will feel more confident interacting.

In a final analysis, the state of North Carolina must act to mitigate the health disparities harming the Deaf and HOH community. While this study outlines numerous factors contributing to these negative trends, none are insurmountable. A joint effort between the state government, medical leaders, and individual practitioners will be vital in serving justice to this overlooked minority. The possible solutions discussed here represent only a fraction of the interventions necessary to accomplish this goal; more research is needed to create a stronger path towards recovery. With the rapid expansion of the Deaf and HOH population, action on this issue cannot be put off for any longer.

References

Barnett, S., McKee, M., Smith, S. R., & Pearson, T. A. (2011). Deaf sign language users, health inequities, and public health: opportunity for social justice. Preventing Chronic Disease, 8(2), A45, 1-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3073438/.

Hommes, R. E., Borash, A. I., Hartwig, K., & DeGracia, D. (2018). American Sign Language interpreters perceptions of barriers to healthcare communication in deaf and hard of hearing patients. Journal of Community Health, 43(5), 956–961. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-018-0511-3.

Parsons, A. (2019, April 9). A different, different world stuns attendees. NC State University. https://socialwork.news.chass.ncsu.edu/2019/04/09/a-different-different-world-stuns-attendees/.

Peter, Y. G., May, M., Paintsil, D., John, & Dansan, D. A. (2018, October 11). Healthcare language barriers affect deaf people, too. Boston University School of Public Health. https://www.bu.edu/sph/news/articles/2018/healthcare-language-barriers-affect-deaf-people-too/#comments.

Sheppard, K. (2014). Deaf adults and health care: Giving voice to their stories. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 26(9), 504–510. https://doi.org/10.1002/2327-6924.12087.

Withers, J., & Speight, C. (2017). Health care for individuals with hearing loss or vision loss. North Carolina Medical Journal, 78(2), 107–112. https://doi.org/10.18043/ncm.78.2.107.

Featured Image Source:

England, B. (2019). Deafness isn’t a ‘threat’ to health. Ableism is [Photograph]. Brittany England Illustrations. https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5aa6ed407c9327ddb90e9ae2/1582141589928-PC6V4QQJBTSDI30Z317C/12448-Deafness_Isn%27t_a_Threat_to_Health_Ableism_Is-1296×728-Header.jpg?format=2500w.