Brain tumor. Only two words until it becomes a diagnosis. This is something no parent wants to hear their child has. It is something no one wants to endure. It is scary and causes one to think about their life in a different perspective.

It was 2018 when a 2-year-old battled a misdiagnosed brain tumor. Her parents questioned what was happening to their little girl as her body functions gave way rapidly. Seven months later, they were forced to say goodbye to their child for the last time. It was not until three years later when their story was shared with thousands after being published in a journal. How was the tumor misdiagnosed? Is it common for this to happen? What were its symptoms? How did this happen to a little girl?

A retrospective study was conducted in an attempt to answer the above questions. The authors consisted of five medical doctors in the Department of Radiology and Neurosurgery in four hospitals and a university in Vietnam. These doctors examined and researched the records of this young girl who suffered from an extremely uncommon brain tumor. They reported a case of extraventricular, atypical choroid plexus papilloma in the cervicothoracic spinal cord of the two-year-old girl. Choroid plexus papillomas are scarce, benign intracranial (within the skull) tumors. In children, they most commonly occur in the lateral ventricles, located in the cerebral regions of the brain. The extraventricular (outside of the ventricle) detection of a choroid plexus papilloma is rare and exceedingly difficult to diagnose (Hien et al. 2021). As a result, they are often initially approached as common primary tumors of the spinal cord.

Choroid plexus papillomas (CPPs) are classified as World Health Organization (WHO) grade I malignancies and account for 0.4%-1% of all intracranial tumors. Grade I malignancies are classified as having cells that look more like normal cells and tend to grow more slowly. They arise from the epithelial cells of the choroid plexus and may occur at any location containing plexus. Epithelial cells of the choroid plexus, located in the ventricular system of the brain, form the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier. Choroid plexus is a network of blood vessels and cells in the ventricles of the brain that produce cerebrospinal fluid. Several sites of extraventricular CPPs have been described in writing as occurring in the cerebellopontine angle, suprasellar region, intraparenchymal areas, and sacral nerve roots. However, this case arose from the cervicothoracic spinal cord.

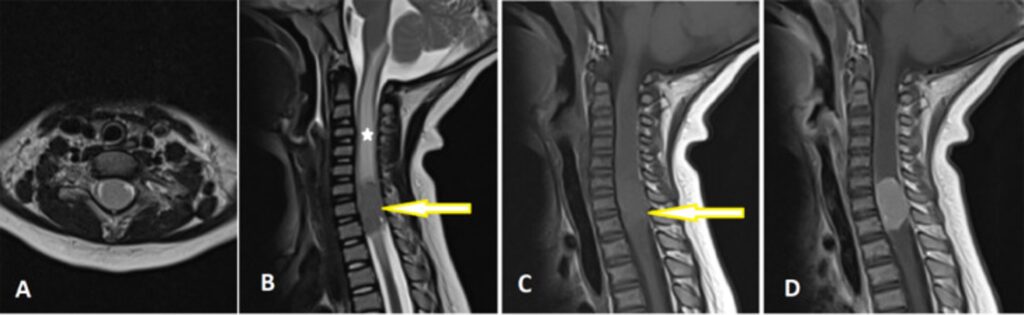

A twenty-month-old patient suffered from abnormal symptoms of weakness in her limbs and difficulty turning her head. She experienced no significant medical problems during the neonatal period; however, her parents began noticing the rapid progression of these symptoms over the course of a month. As a result, she was admitted to the hospital. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an intramedullary, oval-shaped, well defined solid mass at the C7-D2 levels as depicted in the below image (Hien et al. 2021). Intramedullary tumors are growths that develop in the supporting cells within the spinal cord. The C7 vertebra is part of the lower levels of the cervical spine, near the base of the neck, and the D2 level is part of the upper level of the thoracic spine. Syringomyelia, a long-term condition that causes fluid-filled cysts to form inside the spinal cord, was observed on T2-weighted imaging (T2W). The tumor was isointense (having the same intensity) on T1-weighted imaging and slightly hyperintense (having a higher intensity) on T2W compared with the spinal cord parenchyma. No other lesions were detected from the contrast-enhanced MRI of the brain and total spine. Due to the location and general appearance of the tumor, an initial diagnosis of ependymoma or astrocytoma was suggested.

(A) Axial T2-weighted (T2W) image of the cervicothoracic spinal cord shows an intramedullary solid mass. (B) Sagittal T2W image revealed the tumor was located at the C7–D2 level (arrow) with syringohydromyelia (star) and was well-defined and slightly hyperintense compared with the spinal cord parenchymal. (C) Sagittal T1-weighted (T1W) image indicated that the lesion (arrow) was isointense compared with the spinal cord parenchyma. (D) Axial contrast-enhanced T1W image demonstrated homogenous enhancement of the tumor (Hien et al. 2021).

The patient underwent a surgical biopsy with histologic results confirming an atypical choroid plexus papilloma. Because no other lesions were identified, either in the cerebral ventricles or in the spinal cord, the final diagnosis was ectopic atypical CPP in the cervicothoracic spinal cord. The location of the tumor prevented its full removal; therefore, the child received adjuvant radiotherapy. An atypical CPP is considered benign; however, if not fully removed they too require chemo/radiotherapy because they have a high chance of coming back. The goal of the therapy is to kill off the tumor before killing the person. Unfortunately, five months later, the little girl passed away as a result of respiratory distress. On MRI, the tumor had some imaging features consistent with choroid plexus papillomas; however, the oval shape and location were atypical characteristics for CPPs. These imaging features and location made the tumor indistinguishable from ependymoma and astrocytoma, the most common intramedullary tumors that occur in children. Because extraventricular CPPs are exceptionally unusual, choroid plexus papilloma was not considered in the initial diagnosis of this case (Hien et al. 2021).

This case report was able to accurately outline the journey the two-year-old patient had to undergo; however, it came with its share of limitations. The sample size of the study was focused on only one child; tumors do not affect people in the same way. In this case, the child’s tumor was not able to be removed; therefore, this impacted what the outcome was. What if it is removed? Will the tumor come back? How will the patient heal? These questions could not be answered based solely off this study. The authors hinted around the fact that the initial diagnosis of this tumor was incorrect because its location and general appearance suggested other forms of tumors. They also admitted to a choroid plexus papilloma not even being considered in the initial diagnosis of the case. It was not until the patient underwent a surgical removal that the histologic results confirmed an atypical CPP. However, after a brain MRI scan that revealed no further evidence of other ventricular lesions, the case was officially diagnosed as an ectopic atypical choroid plexus papilloma.

Implications of this study include patients being provided with every possibility of what the tumor could be instead of diagnoses being immediately ruled out. Ethically, patients should be informed of accurate details on their diagnosis and prognosis. It is important patients are aware of what to expect, their next steps, best- and worst-case scenarios, the quality of life after treatment, and what to anticipate throughout the healing period. The many misdiagnoses combined with the elimination of all other explanations and the impact on individual’s mental and emotional status are the most controversial topics on these tumors. Tumors may mimic others; however, the type is not fully known until the histology results come in. In this instance, the child’s tumor was misdiagnosed due to it resembling another kind of tumor and being in an awkward location. The actual diagnosis was not considered because of its rareness. This should not be the case; every outcome should be discussed. Similar cases are still arising even though they are infrequent. Today, CPPs are continuously misdiagnosed as other types of tumors, and this case report provides a real example of how and why it happens so frequently.

Another study reporting on the same topic includes imaging findings of extraventricluar choroid plexus papillomas on a retrospective study of ten cases. These tumors were located at similar sites to the two-year-old patient in this case report. Eight out of the ten cases (80%) were misdiagnosed as other intracranial tumors or lesions (Shi et al. 2017). In a young boy, a CPP arose in his brainstem. It was misdiagnosed preoperatively as a glioma. However, after resection of the legion and histopathological findings, it was diagnosed as a choroid plexus papilloma (Xiao et al. 2013). Preoperative imaging normally misdiagnose CPPs as other tumors due to the atypical site of extraventricular CPPs. It is crucial for a differential diagnosis between extraventricular choroid plexus papillomas and other intracranial entities to be determined for the therapeutic approach and prognosis of the patient.

This case report of the twenty-month-old girl is important in providing a real-life example of how choroid plexus papillomas are diagnosed and how they affect the body. It is not common knowledge CPPs are extremely rare and mimic other tumors therefore being frequently misdiagnosed as ependymomas. Some may appear within extraventricular sites making them harder to diagnose. It is critical to inform people is it not uncommon for these types of tumors to not be correctly diagnosed until surgery and histology reports are performed. Hopefully from this study and others that portray similar information, CPPs will be included in initial diagnoses to prevent its increasing rate of misdiagnoses.

References

Hien NX, Duc NM, My T-TT, Ly T-T, He D-V. 2021c. A case report of atypical choroid plexus papilloma in the cervicothoracic spinal cord. Radiol Case Rep. 17(3):502–504. doi:10.1016/j.radcr.2021.11.039. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8685913/.

Shi Y, Li X, Chen X, Xu Y, Bo G, Zhou H, Liu Y, Zhou G, Wang Z. 2017. Imaging findings of extraventricular choroid plexus papillomas: A study of 10 cases. Oncology Letters. 13(3):1479–1485. doi:10.3892/ol.2016.5552. https://www.spandidos-publications.com/10.3892/ol.2016.5552.

\Xiao A, Xu J, He X, You C. 2013. Extraventricular choroid plexus papilloma in the brainstem: Case report. Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics. 12(3):247–250. doi:10.3171/2013.6.PEDS137. https://thejns.org/pediatrics/view/journals/j-neurosurg-pediatr/12/3/article-p247.xml.

Featured Image Source:

Google Images, Creative Commons License