By Olivia Adams, Alison Curry, Hannah Feinsilber, and Sam Gaul

Our project analyzes the Lurcy story through the lens of migration. It follows the many journeys of a solitary piece of luggage once owned by Alice and Georges Lurcy.

Adaptation

Transcript:

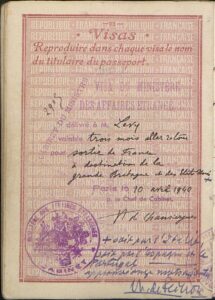

Your name is a crucial factor in the development of a sense of self, and helps propel you forward in various paths of life and career. A personal name identities a specific individual human, giving one a sense of self and acting as an identifier. One’s last name is a testament to their family’s history and can indicate a person’s community. Changing a name is a very personal decision, one that affects so many factors in life and family. Georges Levy, Jewish Frenchman, married Alice Snow Barbee, a Christian American woman, in France in 1937. Georges and Alice Levy, in a desperate attempt to mask their identity and protect themselves, made the difficult decision to change their last name to Lurcy. This name change can be seen in their marriage certificate, originally married under the name Levy and then changing it to Lurcy sometime between the years 1940-1943. As Levy was a recognizably Jewish last name, George felt that it was too much of a risk to enter the United States during the Second World War with this identity tag. Thus, he changed their last name to Lurcy while still living in France, ensuring that they would be safe on their travels from any persecution. This name change was a vital component of their migration – it signalled a beginning of fundamental change and identity transformation for the couple. After changing their name, they had a greater sense of security and felt relieved that they were able to escape the political chaos of World War II.

In order to better understand the Lurcy’s name change, we interviewed Howard Feinsilber. Mr. Feinsilber is the son of Arnold Feinsilber and the grandson of Murray Feinsilber. Murray Feinsilber immigrated the family from Grajewo, Poland to the Bronx, New York City, New York in the 1920s. Murray was an electrical engineer and worked on the New York City subway lighting system. Howie Feinsilber remembers Murray and the story of his family’s immigration. (Arnold, Murray’s son, has severe Alzheimer’s and could not be interviewed). The interview went quite well. We learned about the details of the immigration passage of the Feinsilber family. We also learned the Feinsilbers did not travel immediately to New York City but rather they lived in London for six months. The most fascinating part of the interview concerned the family name change. In Poland, they were the Jeleski’s but in New York the last name was changed to Feinsilber. Feinsilber was the name of the Jeleski’s mailman in New York. Howie was not exactly sure why the family changed their last name but there are several theories. Some say it was to make the family look less Jewish/Polish, as antisemitism was rampant in America in the 1920s. Others say it was just popular at the time to change your last name. This name change is similar to that of the Lurcy. It was raises more questions to why the Lurcy’s changed their name. Was it for style? Or out of fear?

Transition

Transcript:

Georges and Alice appeared to have a very privileged and unique experience during these times, especially as George was a French Jew that migrated to the United States during World War II. They seemed to live a wealthy and affluent lifestyle in America, and from the documents we can also assume that they had the same experience in France, and wanted to flee from persecution in Europe. George made his fortune in a few ways: investing in and helping to develop a hydroplane during World War I, collecting art, and by working as a financial consultant. He was one of the most powerful figures in French finance, and we can assume he had a very high status in society that Alice acquired upon their marriage. Some of the global objects that Alice had in her bedroom while living in the United States (Scan 31) included: porcelain from China and France, a reproduction of a water colour painting, several objects titled “Louis XV” that we can assume came from France. Alongside the objects from across the world were sentimental items; dresses, paintings, and most notably, diamond and ruby necklaces. Alice had a beautiful collection of jewels; earrings, rings, necklaces, remade several times by George to give her the most beautiful gifts. These delicate, expensive collector’s items had travelled across the world to end up in their High Point, North Carolina estate. Inside the Lurcys’ suitcases were not just valuable objects, but memories, treasures, and pieces of their former life. It is compelling to imagine the Lurcy’s packing their emotionally and financially valuable items as they were attempting to flee war-torn France. What did they pack into their suitcases? Which objects did they have to leave behind? These decisions were choices that all migrants had to make. Packing their luggage was just the start of their migration.

Expedition

Transcript:

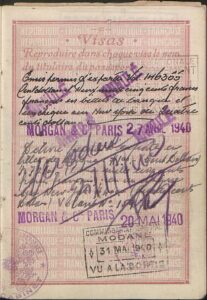

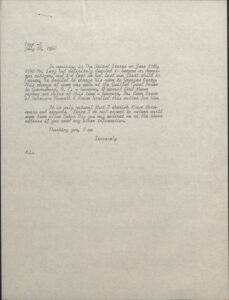

On September 3rd, 1939, France declared war on Germany following their invasion of Poland. Despite this, Georges and Alice Lurcy made no immediate attempt to leave France. The first eight months of the war, commonly known as the “Phoney War,” were quiet and relatively peaceful in terms of military action between France and Germany, and it is likely that Georges and Alice were hopeful of being able to stay in France. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that Georges and Alice were aware of the potential dangers facing France and their own lives. In a letter sent later in her life to a legal representative, Alice quotes Georges, who told Alice “Should I be put in a concentration camp, contact Fernand…” This Fernand, who was Fernand de Brinon, a French ambassador to Germany (later outed as a key Nazi collaborator), was a relative of Georges who would eventually persuade him to escape with Alice as soon as possible. It was this tip from Fernand, coupled with well-deserved fear and conviction, which led Georges and Alice to make their escape from France in the spring of 1940 – prior or concurrent to the Nazi Invasion of France.

Like that of many escaping refugees and Jewish peoples in World War Two, the physical journey that the Lurcys undertook was long, and the specific details surrounding it are not completely known. Thanks to passport records, immigration documents, and family history, we can construct a general trail of locations that the Lurcys travelled through on their migration journey.

According to their family, Georges and Alice departed from France on “the last cruise ship” to depart from the city of Le Havre in the North of France during World War II. It is likely that this departure occurred sometime in late April or early May. A comment in the passport suggests that the Lurcy’s first stop on their journey was in Great Britain, where thousands of Jewish people fled prior to the war. Following a likely but unconfirmed second stop somewhere in Canada, Alice and Georges would arrive in New York City on June 10, 1940, a date that Alice reiterates in later letters. It was in New York, the city where they had met, where Georges and Alice hoped to require some of their finances and prepare for their American life. However, immigration documents indicate that Alice and Georges’ journey was not completely over, with records showing them as having arrived in Miami, Florida on August 9, 1940 from Havana Cuba, travelling on a flying boat known as the “Jamaica Clipper.” The reasons for this unexpected change in port-of-entry are not known to us currently, though possible explanations could be issues with finances, attempts to avoid certain migrant quotas for New York City, or even an unrelated later journey to Cuba. What is for sure, is that Georges and Alice Lurcy, after a long journey, were in their new home of the United States.

We can imagine the luggage being a central companion to the Lurcys while on this journey. As migrants, and eventually as immigrants in a new country, the Lurcys relied on the durability of the luggage for safe transport of their beloved objects. The luggage allowed them to effectively carry their home – their valuables, the evidence of their prior life – with them through their difficult journey.

Eviction

Transcript:

The Lurcy’s migration story extends beyond their initial migration out of France. Alice herself, after Georges’ early death, was forced to migrate once again. For a period of time, Georges and Alice lived in a remarkable mansion at 813 Fifth Avenue in New York City. Consisting of twelve rooms, an elevator, and Georges’ incomparable art collection, the Fifth Avenue mansion was a masterpiece. However, Georges did not leave this house to Alice in his last will. It, like the rest of his belongings, was included as part of his estate when he died, left in the care of trustees. Though Alice no longer owned the house after Georges died, she continued to live there for years. However, in 1960, the property was purchased from Georges’ estate – intended to be torn down and turned into apartment homes. Though Alice put up much of a fight against the sale, even refusing to leave the house in fear of eviction, she finally was forced out. Once again, Alice had to migrate. She once again had to pack this piece of luggage with her valuable and well-loved goods and leave a home that she dearly cared for. When interviewed by The New York Times in 1961, Alice said, “My mind, memory and feelings are too closely tied to this home, where I dwelled with my late husband.” (source, Folder 49, Scan 12). Another connection severed, displaced from another home, Alice packed up her things (whatever was left after the estate sales) and left her home at 813 Fifth Avenue for good.

Preservation

Transcript:

This piece of luggage, a simple object meant to keep things safe, had a long and arduous history. It travelled the world alongside its owners. This piece of luggage followed them through their travels, though much of their journeys were not planned (like their forced migration from France in 1940 and Alice’s eviction in 1961). It also went through a change in ownership after Alice died. Today, Alice’s niece takes care of this piece of luggage. It is just one object through which Alice’s niece remembers her aunt. A remarkable object that survived an escape from war and travels around the world, this luggage reminds us of the durability of migration. Alice herself never forgot her migrant past. As she fought through lawsuits and tax problems after Georges’ death, Alice would often call on her tormented past. She could not forget being forced to leave France. The forced migration from her home, due to her husband’s Jewish identity, was something that stuck with Alice throughout the rest of her life. And, today, her niece cannot forget Alice through the things that she left behind. And one of these objects, this simple yet remarkable piece of luggage, best symbolizes the Lurcys’ migration story. The Lurcys are remembered for their things – Georges’ remarkable art collection, Alice’s impressive jewelry and clothing. Their outstanding wealth and privilege afforded them the ability to leave Europe during the Second World War. It also helped them establish a new life in the United States. Though many of their objects remain, whether in museum collections or in the safeguarding hands of family, it is this piece of luggage that most eloquently reminds us of their migration story.

Sources for further exploration:

On Jewish name changes:

Fermaglich, Kirsten L. A Rosenberg by Any Other Name: A History of Jewish Name Changing in America. 2018.

Ekholm, Laura Katarina, and Simo Muir. “Name Changes and Visions of ’a New Jew’ in the Helsinki Jewish Community.” Scripta Instituti Donneriani Aboensis, vol. 27, 2017, pp. 173–188., doi:10.30674/scripta.66574.

On migration:

Bachmann-Medick, Doris and Jens Kugele, eds. Migration : Changing Concepts, Critical Approaches. De Gruyter, Inc. 2018.

On Jewish life in France prior to and during World War II:

Poznanski, Renée. Jews in France During World War II. Brandeis University Press in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 2001.

Credits:

Art and videography – Hannah Feinsilber

Voiceovers – Olivia Adams, Samuel Gaul, and Alison Curry

We would like to thank Mr. Howard Feinsilber for participating in our interview and sharing his family’s story with us.