By Caitie Thompson, Seth Tysor, Hannah V., and Xiangman Zhao

Welcome! In the audio podcast and transcript below, our group examines the themes of diaspora, preservation, and identity as expressed through the complex life story of Georges and Alice Lurcy. We consider the notion of diaspora through three lenses (1) The Jewish Exodus, (2) Georges' move from France to the U.S., and (3) Alice's eviction from her 5th Avenue Mansion. Please view our additional sub-pages for original interviews, further readings, and supplemental materials that contribute to a more detailed study of these broad themes.

Podcast Transcript

Provided below is the transcript of our podcast conversation in which we discuss the themes noted above. Feel free to read along while listening!

Seth: WELCOME WELCOME WELCOME!!

Caitie: …to our first-ever recording of this podcast! I am joined here today with…

Seth: My name’s Seth!

Xiangman: I am Xiangman!

Hannah: And I’m Hannah!

Caitie: And I’m Caitie! And today we will be conducting an episode on Jewish material culture. Throughout this semester we have examined material culture from a multitude of different lenses. Specifically discussing many Jewish material objects and their presence within diasporas. Within this Podcast we will be discussing the history of Alice and George Lurcy’s story and specifically discussing the Jewish Exodus and a brief history of Jewish Diaspora as a whole, Georges’ Diaspora from France to the United States, and Alice’s forced diaspora from her 5th Avenue Mansion; while also relating these diasporas to a theme of preservation.

Caitie (Jewish Diaspora): The first thing we’re talking about today is the history of the Jewish diaspora from a broad lens. Diaspora is a Greek word meaning dispersion or the act of dispersing, and quite literally, this is what happened. There was a significant dispersion of Jews among the Gentiles after the Babylonian exile. This act of exile was what forced the Jews from their ancestral homeland and into other parts of the globe to settle, thus causing the diaspora or starting it. From the exile, Jewish communities scattered throughout the outside of Palestine or what is now known as present-day Israel. This is an example of diaspora but throughout Jewish history, there have been numerous accounts of mass expulsion which lead to the diaspora. The term diaspora literally refers to the physical dispersion of the Jews throughout the world and places other than the ancestral homeland, but it also holds a deeper meaning as we have seen throughout our study of the Lurcy Archives. This term also carries religious, philosophical, political, and even personal meaning from story to story. As a result of the diaspora, there is a special relationship between these people who were dispersed and the land of Israel.

One example of a significant diaspora from a biblical outlook is the Exodus. This example of the diaspora is very influential to the history of the Jewish diaspora and culture. A quote from “Why The Exodus Was So Significant” by Rabbi Irving Greenberg really encompassed the influence of the Exodus. This quote states: “The impact of Judaism’s transformative event is felt by the other monotheistic religions.” The story of the Exodus is one that presents significant meaning to Jewish people. This diaspora from Egypt was not only the formative event in the history of the Jewish People but was an unprecedented event for Egypt. This movement of the Israelites from Egypt to end up at the borders of Canaan represents their diaspora. This story is one that is central to Judaism, as is it referenced throughout daily Jewish Prayer and even celebrated in Passover. Another early example of a significant Jewish diaspora is the Assyrian exile, which consists of the expulsion from the Kingdom of Israel (Samaria) which was started by Tiglath-Pileser III of Assyria in 733 BCE. Later on throughout the middle ages, due to rapidly increasing migration and resettlement, Jews split into specific regional groups which today are generally recognized according to two primary geographical groupings: the Ashkenazi of Northern and Eastern Europe, and the Sephardic Jews of Iberia (Spain and Portugal), North Africa and the Middle East. All of these notable examples of Jewish Diaspora further support our understanding of diaspora, and thus further expanded our understanding of the Lurcy story we are discussing today and the diaspora he and his objects experienced.

Seth (Georges’ Diaspora): The second topic we will discuss concerns Georges Lurcy’s diaspora from France to the United States due to the beginning of World War II and the onset of the Holocaust. Georges Lurcy was a French businessman who met a North Carolinian woman from local High Point, named Alice Lurcy, at a bank where Alice carried a job, arranged for her by her uncle. In an interview with Alice’s niece, Alice Nelson, she explained to us how the relationship between Alice and Georges began to grow as Georges and Alice spent more time together. While the two were establishing their relationship, a French ambassador began to advise George that he would need to immigrate to the states because of the emerging war. Alice’s uncle wrote her a letter explaining how he was selling his house and wanted to know whether or not Alice and Georges would like to buy it. The couple decided to buy the house and moved in together. According to Alice Nelson, the couple “struck the town with lightning,” with Alice’s beauty and her having a Frenchman as a husband. Alice began to integrate Georges’ life into the NC lifestyle while in High Point. The two also exchanged many love letters and material objects to express their affection towards one another, such as many paintings and fine jewelry.

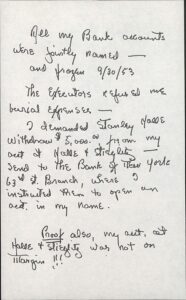

Located above are two documents that come from the Lurcy family archives and were written by Alice Lurcy herself to her bank. These help illustrate some of Alice’s legal and financial struggles after the death of her husband, Georges.

Moving onto Georges’ educational experience in the states, Mr. Lurcy also attended the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill where he earned his masters and later attended Columbia University where he earned his Ph.D. As he earned his credentials, Georges’ relationship with Alice was also a political advancement as he was married to an American woman. As his reputation grew, so did his monetary wealth. Georges began to purchase many material objects that signified importance to him, Alice, and his Jewish faith. Georges was extremely attached to many material objects that helped him maintain a sense of identity as he was forced to immigrate to America, similar to how his ancestors were also forced to leave their homes. The struggle with maintaining the relationship with his material objects as he was forced to leave was prevalent and most likely caused extreme heartache to Georges, which brings us to the topic of dissemination through preservation. When Georges died, he did not leave his 5th Avenue Mansion in New York City to Alice; instead, he allowed the mansion and the objects within it to be sold to many people. One speculation as to why Georges decided to do this was because he wanted his legacy and history to withstand another potential diaspora. By allowing many of his objects, all of which housed his identity and memories, to be sold to different people, he was able to preserve his memory throughout the country. According to the folklorist, Vanessa Ochs, author of Inventing Jewish Ritual, Ochs writes in her essay that, “We also experience material objects as vessels of identity and memory, and we understand that when an object becomes an heirloom or a souvenir it increases in value.” (Ochs 92) Material objects, both profane and sacred, house memories that shape our identities. Georges Lurcy’s identity was that of a successful Jewish businessman who was forced to immigrate to America for chances of a better life. Every day, people are forced to leave their homes for the chance at a better life and to chase their dreams, and what they carry with them defines what is most important to them. What they leave behind may never be seen again. Georges Lurcy did not want this repeated occurrence to happen to him for a second time which brings us to the conclusion of his decision to preserve his identity through disseminating his most prized possessions. This brings us to our next topic, the forced diaspora of Alice Lurcy.

Xiangman (Alice’s Diaspora): The third topic is about Alice Lurcy’s diaspora, especially on her eviction from the 5th avenue mansion in New York due to Georges not leaving her sole custody in the will. The picture is the newspaper on her eviction. Even though Alice is not Jewish, I will still frame her expulsion from the 5th Avenue Mansion as a diaspora, as she has been made an alien in her own home. Material culture is not something specific to Jewish, Alice also relies on the house and all the paintings left by Georges to keep Georges alive with her. These objects remind her of the memories of Georges and help her to still feel George’s love and maintain the connection with him. From love letters between her and Georges, we know that they had a very happy marriage and they really love each other. Alice really wants to preserve her husband, Georges, through retention and make the 5th avenue mansion into a museum. She wishes to preserve her husband by establishing a consistent, immovable, eternal home where he might remain present and where others might continue to interact with him by interacting with his material possessions.

Alice’s diaspora is more like her own personal diaspora, which links to material culture more broadly. People will keep things that have special meanings for them. At the beginning of the semester, the first day of class, everyone just shared an object that tied to their religious or cultural identity. I remember that I showed a Chinese knot in my room which means good luck. I made that knot in middle school and it is a Chinese tradition to hang a red Chinese knot above the front door during the Spring Festival. The Chinese knot also reminds me of a lot of happy moments I spent with my family. What special objects do you guys have?

Hannah: On the first day of class I showed the ring that I got for my confirmation. I actually lost it a few days ago and found it and I was freaking out and it attests to this whole idea of how special objects can be. It takes me back to a certain time and place in my life and I am sure it is the same for you guys. What about you Caitie?

Caitie: I have a necklace my great aunt gave to me when I was really young and it is actually my birthstone for September and my great aunt’s birthday is also in September, so it’s actually something that we share. She is still alive, in her 80s, but when she first gave it to me I did not really appreciate it and it has been sitting in my jewelry box and until recently, specifically on my 17th birthday, I started wearing it and it is something that I get to hold close to my heart. I never take it off. I shower with it and it is a special object to me because a family member gave it to me and I can always think about my great aunt when I am wearing it.

Seth: My object is a bible that my grandmother gave me when I was younger. She would always take me to church and she truly was the founder of my faith. She got me going to church a lot and she taught me a lot about the bible and what it means to be a Christian. I will always cherish that bible; I still use it today when I study the bible or go to church. The first page actually has her handwriting on it that says something around the lines of how she is dedicating this bible to me and how she hopes it will guide me in the right direction as long as I live by its word.

Xiangman: It is especially common for living to maintain ongoing relationships with the dead through preservation. The residual belongings of the dead are used to evoke memories. In the book “Death, Memory and Material Culture,” Elizabeth Hallam says that “At the time of death, embodied persons disappear from view, their relationships with others come under threat and their influence may cease. Emotionally, socially, politically, much is at stake at the time of death. In this context, memories and memory-making can be highly charged, and often provide the dead with a social presence amongst the living.” This quote also reminds me of the movie Coco which talks about memory and death. That’s one of my favorite Disney movies. The movie says that “When there’s no one left in the living world who remembers you, you disappear from this world. We call it the Final Death.” My mom also keeps my grandfather’s watch with her to keep him present with her, which also reveals the importance of material objects in mourning and memorizing.

On the other hand, Alice’s diaspora represents and embodies the sufferings of the Jewish people during the Exodus, as well as George’s departure from France. Alice is a strong and independent woman who holds stock shares of multiple companies and makes donations to local museums. However, when she is evicted from the 5th avenue mansion, I can feel her weakness and helplessness. The feeling of desperation is very similar to Jewish people during the Exodus.

Hannah (Theme of Preservation):

Yeah, thank you Xiangman, and thank you to my wonderful group members who have been framing this really kind of incredible story. As we’ve been discussing, we’re really viewing diaspora on three levels: the Jewish diaspora, Georges’ diaspora, and Alice’s diaspora. We’re also coming to a conclusion about Georges’ diaspora and the preservation, and therefore Jewish diaspora and preservation by exploring three main premises.

One of the ways we’re choosing to frame and understand these larger concepts and the relationship between dissemination and consolidation that constitutes preservation is by first analyzing Georges Lurcy’s relationship to his objects, his material wealth and possessions, which comprises our first premise. That begs the very obvious question: what was Georges Lurcy’s relationship to his material wealth and possessions? Through the exploration of these folders and the time we’ve been spending with this project, it’s very apparent that Mr. Lurcy took great pains to get his belongings from France. A lot of the sources that we’ve been reading kind of delineate some dramatic legal battles that are occurring and some of the problems he had getting his things from France to the US, and even maintaining his French estate. He took great pains to get his things here and something that’s interesting that Alice mentions in one of the letters that she sends to the banks that she’s kind of embroiled in some legal battles with, she says: “Mr. Lurcy was older and wealthier and Jewish as Dr. Bernstein,” who was an executor of Georges’ will, “and as an Economic student he was most interested how they were able to save their lives as well as money from Hitler.” Immediately we kind of have this interesting conflation between life and material wealth, between identity and the objects we confer identity on, and therefore the objects that confer identity on us. That’s something we’ve been exploring through this whole class, and it’s a chicken-and-the-egg scenario—we don’t really know what comes first. The relationship we have to our objects, to the things we own is very much a co-constituting relationship, and my understanding of the Lurcy project and what we’ve been analyzing in this project has been helped by certain outside sources, one being “Why We Need Things” by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, in which he says, “…I wish to emphasize that our dependence on objects is not only physical but also, more importantly, psychological. Most of the things we make these days do not make life better in any material sense but instead serve to stabilize and order the mind.” At a very [common] human level, we can infer how Georges Lurcy felt about his objects, and incorporate what Csikszentmihalyi says to our understanding. It makes sense that if you’re dispossessed of your home, that you would then cleave more strongly to your possessions, it makes sense that if you are denied a sense of belonging, that you would then care more for your belongings, because as we’ve discussed often in this class, and as the Ochs quote that Seth mentioned bears out as well, material objects have this ability to establish place, to establish a sense of home and identity and as Csikszentmihalyi says, they order and stabilize the mind, and Mr. Lurcy was undoubtedly undergoing a great deal of psychological peril and turmoil as he was really having to flee for his life, being coercively sent from his home. That tells us something about his relationship to his material wealth and objects, but also just thinking about material wealth in general, when you’re moving from one country to another, material wealth cushions you, it helps you make that transition, you’re bringing the ground that you wish you build upon, and as Csikszentmihalyi suggests, we build new submarines because we have old submarines, we are never truly building, we are always and only ever building upon, and so Georges’ desire to retain his possessions gave him grounds to build upon physically and psychologically as he was experiencing the turmoil of diaspora.

And so with this in mind, with Georges’ relationship to his objects firmly established as a part of our thesis, we move to this second premise where we discuss this relationship between dissemination and consolidation in the life of Georges Lurcy, but also in the life of the larger Jewish community, and the way that we’ve done this is by analyzing two opposed narratives of Alice Lurcy and the executors of Georges Lurcy’s will. And we’re discussing dissemination and consolidation as two distinct forms of preservation before moving into our third premise.

Alice embodies this preservation through consolidation, through rooting in a certain environment, because she mentions that it is her desire—because it is Georges’ desire—that at one point he said he wished to retain and consolidate all of their belongings and make their 5th Avenue Mansion into a museum where people could come and interact with his things, with his objects, so essentially she—and ostensibly Georges, according to Alice—wanted to establish a fixed home that Mr. Lurcy could supposedly “live in” after his death through his objects. It was Alice’s desire—and Georges’ desire according to Alice—that he have a very strong presence in a single place rather than a weaker presence in a multitude of places.

And this brings us to the opposed narrative of the executors who said just the opposite, they said “no, in the will it says that Georges wanted to give these things away, he wanted them sold, he wanted the proceeds and these things given to charities, he wanted these things disseminated.” He wanted to be preserved and kept alive kind of the way flowers propagate by having their seeds carried by pollinators who disseminate them all over the place so they can grow in different places as opposed to the single place where they are more likely to die if they don’t move.

And so, these two opposed narratives, all of this is very fraught, this relationship between dissemination and consolidation, because we don’t actually have Georges’ last will, we don’t actually know what he wants, all we do have is Alice and her narrative of consolidation and saying that there’s abuse and fraud occurring that this isn’t what Georges wanted, and the opposed narrative of dissemination by the executors who are saying that no, Georges willed to be persevered through dissemination, to have his objects live on in many places, so this then brings us to our third and concluding premise where we analyze how it’s not just dissemination or consolidation that allows for preservation, but how both constitute preservation and how the oscillation between the two, how the relationship allows for preservation and this informs and is informed by a much broader Jewish story.

This broader Jewish story is what Caitie was talking about, this constant cycle of Jews becoming natives only to become foreigners only to become natives and foreigners again in a constant cycle of dispossession and repossession, where they become natives to a land and find home and consolidate there, and then for whatever reason are disseminated or made foreigners in their own home and disseminated and become foreigners in other places only to become natives and make home again. There’s this constant cycle, and if we want to use the flower metaphor again, yes the pollinators are going out and disseminating these seeds, but if pollinators don’t consolidate the nectar from these flowers, take it home, make it into food and energy so that they can survive, then they can’t go back and do the work of dissemination, they have to have enough sense of consolidation and home to be able to do that, so what we’re really looking at through the Lurcy story—the very personal Lurcy story—is a history of a people group who have experienced diaspora and uprootedness throughout their whole history and then become rooted in the new environments that they are carried to and making a home there and consolidating only to disseminate again. This kind of brings up yet another theme of adaptability that’s been present in all of the interviews that we’ve done for this project, on the level of just being an animal and an organism—because we humans are animals and organisms in an environment—we on a very basic level learn to adapt to climate, to the food a certain place offers, we learn to adapt to the brute physical elements of a place, of an environment, but as humans—which we regard as different from animals in certain ways—we’re not just adapting to brute physical elements, we’re adapting to customs and culture, to ritual, to material culture, to ideas and beliefs and what that ultimately means is that we’re not just adapting to a new environment, but we’re adapting to a new home and making a new home, and home as it is comprised by the relationships with other human beings. There’s this idea as well that if you get to keep your family, you can weather all the storms. And this makes me wonder even more about Georges Lurcy’s true will, what he really wanted. Did he really will all of those things to Alice so she could keep them and keep his memory alive with just her? Or maybe at the end of his life he found a home with Alice, whereas he had formerly depended on his physical objects to make a home in the US to cushion him, to be a psychological support for him, maybe towards the end of his life he found he didn’t need that anymore, because he’d found this home with Alice, a home, a place of consolidation that then allowed him to move on and disperse, to give his objects away. This story, it’s a very Jewish story, it’s a very human story, and it’s been one that’s been very rewarding for all of us to discover, and I’m gonna turn this back over to my groupmates to get some final concluding thoughts, your takeaways and stuff like that.

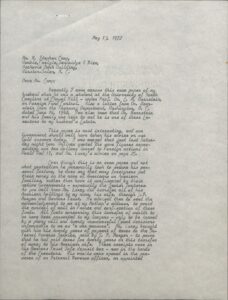

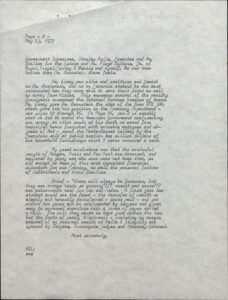

Located above are two documents from the Lurcy family archives that are letters addressed to Mr. R. Stephen Camp from Alice Lurcy. It is from these letters that we pulled the quote used in our podcast. They also help further illustrate Alice’s struggle to retain her and her husband’s belongings.

Caitie: Wow. While we have reflected upon these three levels of diaspora, I feel it is important to have a full understanding of each level of diaspora, while also understanding how these all three are intertwined. After hearing Hannah’s analysis of the themes present throughout the diaspora, these understandings are clear. A quote from the book Diasporas by Kim Knott, Seán McLoughlin states, “Diasporic identities and processes are forged through the production, circulation, and consumption of material things and space.” This quote further supports our semester understandings of the relationships between the diaspora and material culture. As this semester and project are coming to a close, I will take away the idea that through dissemination and consolidation there are forms of preservation. Which encompasses our understanding and main points beautifully. This idea and interpretation of preservation we have obtained throughout this project is something I will take with me throughout my life.

Seth: My takeaway from this discussion is how important material objects are to people in everyday life. Whether an object is labeled as profane or sacred, it has the opportunity and capability to withhold memories of a person’s life and personal identity. Georges and Alice Lurcy’s story shows me how material objects are capable of so much more than being a substance of use or visual appeal. Throughout this class, we have discussed how the Jewish religion harnesses the use of material objects as a means of personal identity within the Jewish faith. By preserving one’s identity and history through material objects, one can both display what means most to them during their life and elicit memories of importance that shaped them into who they are today.

Xiangman: I feel the same. I never really thought about the meaning of objects before this class. Most of the time, I just think about the usability or the practical importance of them. I not only learn how important a material object is to show people’s identity but also being able to link it to my own experience. As an international student and atheist, I can always find similarities between me and all other classmates either Jewish or non-Jewish, and feel connected. The podcast will remain an immovable virtual object for me and reminds me of the fun class and this amazing project.