By Alina Shcherbakova, Adam Spector, Maya Spencer, and Jay Taylor

Our group’s focus, folder number 16 in the archive, centered on the love between Georges and Alice that withstood the test of time. It sheds light on how innocent everyday objects, like handwritten letters, may carry significance beyond the words on a page.

Where did it all begin?

“Love was there from beginning to the end” -Lewis, Alice’s niece

“They had a real love — theirs was a real love affair” -Alice Nelson, niece of Alice Lurcy

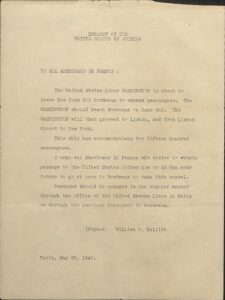

From the contemporary accounts of Alice and Lewis Nelson, Alice Lurcy’s niece and her husband, “Georges had no idea he would end up in the U.S.” Fate determined that a bank would hire Alice Barbee as a secretary before Georges Lurcy arrived in the U.S. from France. Georges visited the bank and the two quickly established a lifelong relationship. Georges returned to his home France and Alice soon joined him there. They were married in Paris in 1937 and to Georges, his wife Alice was the most beautiful woman in the world, becoming “an asset politically and for her beauty.” They lived a comfortable life in France until the horrors of WWII dawned on them. A government secretary warned them about the perils of the oncoming war, and they fled to the U.S. on the last boat out of France as so many Jews were fleeing home countries due to rising antisemitism.1

From the contemporary accounts of Alice and Lewis Nelson, Alice Lurcy’s niece and her husband, “Georges had no idea he would end up in the U.S.” Fate determined that a bank would hire Alice Barbee as a secretary before Georges Lurcy arrived in the U.S. from France. Georges visited the bank and the two quickly established a lifelong relationship. Georges returned to his home France and Alice soon joined him there. They were married in Paris in 1937 and to Georges, his wife Alice was the most beautiful woman in the world, becoming “an asset politically and for her beauty.” They lived a comfortable life in France until the horrors of WWII dawned on them. A government secretary warned them about the perils of the oncoming war, and they fled to the U.S. on the last boat out of France as so many Jews were fleeing home countries due to rising antisemitism.1

In the New World, they settled in High Point, NC, where “they struck the town with lightning.” Residents of High Point knew that Alice Lurcy was beautiful but to have a Frenchman as a husband was “very unusual.” Further peculiarities included this family’s wealth. One might assume that the stereotypical refugee would lack material wealth as the diasporic nature of the flight would cause a family to leave objects behind, however, in an exceptional case of material preservation, the Lurcy family was able to keep most of their belongings during World War II and therefore had greater ability to choose the items they preserved. In fact, they even resorted to “underhanded ways to [move certain objects from France to the U.S.]” as Georges knew underground operators and could pull some strings.

Among the objects they saved, they chose to keep items that expressed their love for one another. Postcards and love letters filled with fragrant-looking roses reveal their attachment to each other and the significant value they placed in these objects that showcased their relationship. Through these letters, we see that any object that moves through space and time can communicate cultural meanings, values, and practices, as well as sentimental attachment, and all of these features help illuminate broader experiences.

~~~~~~~~~~~~•♥•~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Letters

From Georges to Alice

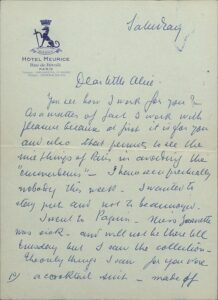

Saturday

Dear little Alice

You see how I work for you? As a matter of fact, I work with pleasure because at first it is for you and also that permits to all the nice things of Paris in avoiding the [?] – I have seen practically nobody this week. I wanted to stay put and not to be annoyed.

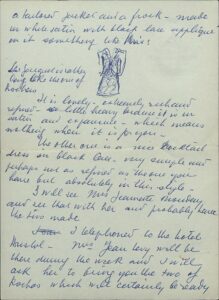

I went to Paguin – Miss Jeanette was sick – and will not be there till Tuesday but I saw the collection – the only things I saw for you were a cocktail suit – made of a tailored jacket and a frock – made in white satin with black lace appliqué on it something like this: [picture of suit].

It is lovely – extremely rich and refined – little heavy because it is in satin and expensive – which means nothing when it is for you.

The other one is a nice cocktail dress – very simple and perhaps not as refined as the one you have but absolutely in this style.

I will see Miss Jeanette Monday and see that with her and probably have the two made.

This letter hints at the intimate nature of Georges and Alice’s relationship. In it, Georges shares small details of his life with Alice by saying he saw “practically nobody this week,” suggesting that Alice is the only person he would have liked to see on his trip. The fact that he sought time to go to Paguin to actively shop for Alice while thinking about her individual taste means that he cares an extensive amount for her well-being. Throughout this whole time, he said that seeing the price tag of the clothing made of materials such as lace and satin would not deter him from purchasing the cocktail dress or suit, representing his prioritization of her. The fact that they decided to keep this after settling in the U.S. shows how attached they felt to invaluable letters that expressed their love for each other rather than merely their extensive collections of paintings and other valuable marketable objects.

The Lurcys’ letters therefore present their personal diasporic experience and showcase one of their core values–their love. We see that any diasporic object can represent a diasporic journey. In the Lurcy family’s case, their love letters tracked their journey from Europe to America.

What about you?

How do the material objects that you’ve traveled with reflect your values?

Ramit Spencer, an immigrant from Israel, answers:

Jewish diasporic objects are part of our Jewish identity. It’s how we celebrate our traditions and holidays. It’s what bring us together— families and communities alike. The shabbat candle holders and the chanukia are two objects I can think of that bring my family together. Every Friday when we light the Chanukah candles is a special time with my family. I truly cherish that tradition and feel connected to my Family through generations— the ones that came before us and hopefully future generations. There are many traditions I celebrate here that I did not celebrate in Israel. We did not say the blessings at shabbat and just simply lit the candles. We did not have a mezuza at the door; here, we do. In general, our parents raised us as Israelis and that meant seperation from old traditions. I am glad that in my home here we do celebrate old traditions that bring us close as a family and to the Jewish community .

Similar to Ms. Spencer, a freshman at UNC writes:

In my household and in my family’s households, I know that shabbat candle holders hold a lot of significance. They are passed down from mother to daughter and I know that my mother cares a lot for them and invests in them. I’m not as religious as my mother or grandmothers but I do see value in objects being passed down from generation to generation. Some other objects include Hamsas that we hang in the front of our house, crystals that I inherited from my great grandmother, and a ring that I have that my grandmother got for her 16th birthday. I also have a small silver menorah that I received for my Bat Mitzvah from my family in Israel. The hamsas remind me of Israel and my middle eastern origin. The ring and crystal remind me of my grandmothers— specifically my Grandma’s life experience and her relationship with my grandfather. The crystals remind me of my great-grandma and how she survived the Holocaust. They’re less about the objects and more about the story for me and remembering the family I have in Israel.

From the interviews, we can see that although Ramit Spencer and the UNC student are separated by a generation or two, one of the objects they chose to describe, the shabbat candle holders, reflect their families’ cultural value of honoring the Shabbat tradition. Traditions like the Shabbat then proceed to unify a people that have been traditionally displaced throughout history. Thus, we can see the power of material objects to continually renew community loyalty and merge generations over time.

~~~~~~~~~~~~•♥•~~~~~~~~~~~~

Continuation of Georges’ Letters

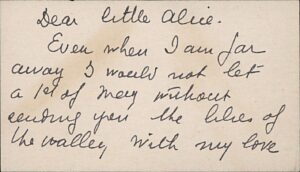

Dear little Alice

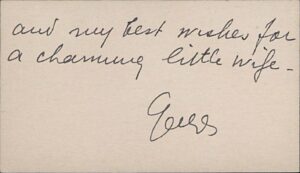

Even when I am far away, I would not let a 1st of May without sending you the lilies of the valley, with my love and my best wishes for a charming little wife.

-Georges

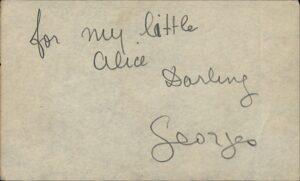

For my little Alice darling.

-Georges

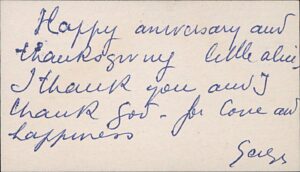

Happy anniversary and thanksgiving little Alice,

I thank you and I thank God- for love and happiness.

-Georges

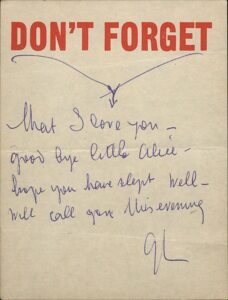

Don’t forget that I love you- goodbye little Alice- hope you have slept well- will call you this evening.

-GL

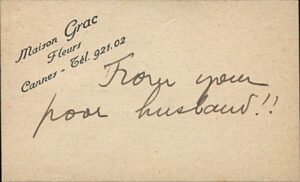

From your poor husband!!

Georges’ commitment to Alice prompted him to send numerous letters to her. Even though these previous letters are short, they are nevertheless signs of Georges’ dedication to his wife. Astounding was the Lurcys’ ability to preserve their objects including these letters, as millions of Jews from 1930 on faced ongoing loss and attempted retrieval of stolen possessions.3 The theft of Jewish property in the Holocaust involved the bureaucratic regime that transferred the property into wealth for the Nazis, which benefited Europeans and their livelihoods. In fact, Jewish property became a type of currency that delayed violence or death but did not necessarily prevent it. Therefore, Alice and Georges Lurcy were fortunate in not having experienced extensive, authoritative property seizure after fleeing from Europe, and successfully transporting their possessions that became cultural objects highlighting the Jewish diasporic experience.

~~~~~~~~~~~~•♥•~~~~~~~~~~~~

Their Luxurious Lifestyle

As shown in the newspaper clipping, the Lurcys had access to the greatest luxuries. Their art collection, with paintings from the likes of Renoir and Gaugin, sold at auction for records of $1,708,500, in 1950s money. Buyers of the Lurcys art collection included both the Rockefeller and Ford families. Despite this immense wealth, Georges and Alice remained steadfast in their commitment to one another, which is evident in their choice to preserve items that held sentimental value, rather than only considering an item’s market value. The love letters seen throughout this exhibit demonstrate how, even in the presence of ample material means, the Lurcys valued deeply objects that represented their commitment to one another.

~~~~~~~~~~~~•♥•~~~~~~~~~~~~

Letters From Alice to Georges

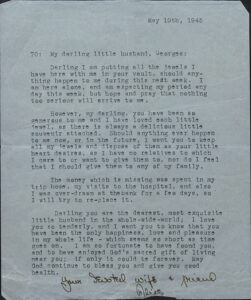

In this letter, Alice expresses her vulnerabilities by suggesting that she would be powerless were anything to happen to her within the next week. Although she prays that “nothing too serious” would “arrive” to her, she feels secure in entrusting jewels that Georges gifted her to her husband. The way that Alice depicts the jewels makes them seem valuable not for their exorbitant price, but because of their intrinsic value as gifts that express Georges love for her. This is because she mentions his generosity to her before she delves into her discussion on the logistics of him keeping the jewels. At the end of the letter, she also capitulates to his exquisiteness as a husband and her fortune to have found him. She describes him as her “only happiness, love, and pleasure in [her whole life],” which demonstrates that the material object he gifted her as well as the letter itself are worthy of keeping because of their relative sentimental value rather than their value as a commodity.

Even though the jewels started out as commodities sold on the market, Alice’s clear unwillingness to ever sell them shows that Georges’ gifts did not remain commodities for long. The jewels instead became nostalgic items and tools to share the Jewish experience as items that wove themselves into a Jewish family.

Like Alice’s jewels, an object that underwent a similar meaningful historical and migratory process was a doll that one Holocaust survivor kept with her after she fled from WWII. Not only did the doll became a special treasure to her, but it also became a cultural medium that acts to preserve the Jewish diasporic history and its subsequent trauma. In this video, this Holocaust survivor shares her experience hiding in a Christian home with her mother during Kristallnacht while her father was taken away to a concentration camp. She describes how the doll she carried with her out of Germany, Inga, wore the same pajamas she wore that night. It is no wonder, then, that this woman treasures it as a personal item despite its potential to sell as a vintage item on the market, for the doll is a tangible piece of evidence that speaks to the hardship Jewish people experienced.

~~~~~~~~~~~~•♥•~~~~~~~~~~~~

Flowers

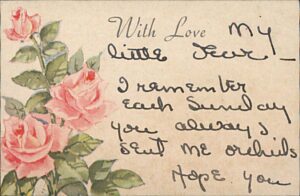

With Love my little Jewel –

I remember each Sunday you always sent me orchids.

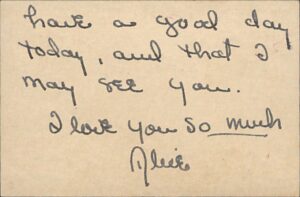

Hope you have a good day today, and that I may see you.

I love you so much

Alice

Alice represents expresses her gratitude to Georges through a love letter wherein she remembers him sending her orchards every Sunday. She creates a serene mood through the inclusion of roses on the letter, making it stand out in its beauty among the rest. Georges and Alice visibly appreciated this letter enough as they kept it with the rest of their highly priced objects, revealing their high appraisal for this object as a sentimental item as it elicits positive memories that awakened their appreciation for life.

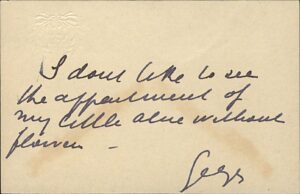

I don’t like to see the appearance of my little Alice without flowers.

GL

Similar to the previous letter, this one indicates Georges’ habit of sending Alice flowers, often without a “celebratory” reason, such as a birthday or anniversary. In that letter, we see Alice’s perspective of deeply appreciating the flowers that Georges sends, and here we see Georges’ perspective of simply seeing his wife and wanting her to have flowers as adornment. It is a gesture of love towards her.

~~~~~~~~~~~~•♥•~~~~~~~~~~~~

One Last Letter

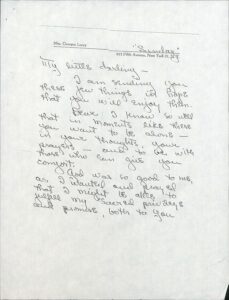

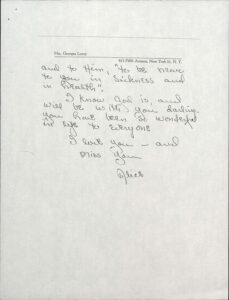

I am sending you these few things in hope that you will enjoy them.

Dear I know so well that in moments like this you want to be alone – in your thoughts, your prayers – and to be with those who can give you comfort.

God was so good to me, as I wanted and prayed that I might be able to fulfill my sacred privilege and promise, both to you and to Him, “to be near to you in Sickness and in health.”

I know God is and will be with you darling. You have been so wonderful in life to everyone.

I love you – and miss you

Alice

This seems to be one of the last letters written between the couple before Georges’ death. It is also clearly damaged; in fact, each page is a stitched-together image of two separate scans of pages torn in half. Despite its imperfections, it was preserved and is easily legible. This suggests that great care was put into preserving it. As we can see, there are rich and varied responses to the pressures that diasporic experience places on people. Subsequent intervention into the archives will therefore bring out further cultural values and meanings as every object tells a story.4

___________________________________________________________________________________

- Gitlelman, Zvi. 2018. “The New Jewish Diaspora: Russian-Speaking Immigrants in The United States, Israel, and Germany.” SHOFAR: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies 36 (3): 164–94. http://search.ebscohost.com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=jph&AN=IJP0000101705&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

- David Gerlach (2017) Toward a material culture of Jewish loss, Jewish Culture and History, 18:1, 17-33, DOI: 10.1080/1462169X.2016.1277073

- Knott, Kim, and Seán McLoughlin. 2010. Diasporas: concepts, intersections, identities. London: Zed Books.