LES GRAVEUSES EN TAILLE-DOUCE: PROFESSIONAL WOMEN PRINTMAKERS IN PARIS, 1660-1789, PhD Dissertation (2024)

Art historical analyses of eighteenth-century French women are often limited to the study of famous patrons or the few female members accepted to the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in Paris. This dissertation calls for a more inclusive Art History by examining one group of women artists who worked outside of the Academy, were typically part of the working class, and employed media considered less prestigious within the realm of fine art: prints.

Intaglio printmakers engrave or etch images onto copper plates which are then printed onto paper. Prints were relatively inexpensive works that could be reproduced and disseminated widely. Though women were an integral part of printmaking workshops since the invention of the printing press, their participation has been historically downplayed or outright erased.

Martin’s research has uncovered 175 “forgotten” women printmakers of eighteenth-century Paris. Contrary to previous scholarly belief, most signed their work, participated in projects within and outside the family workshop, and continued their careers after marriage. Rather than relying on traditionally masculinist fine-art institutions, they achieved success via familial networks and community-oriented professional spheres where daughters, wives, and mothers were an integral part of artistic production and livelihood.

THE IDEAL CITOYENNE: WOMEN, CLASS, & THE FRENCH REVOLUTION IN PHILIBERT LOUIS DEBUCOURT’S FINE-ART PRINTS, MA Thesis (Summer 2015)

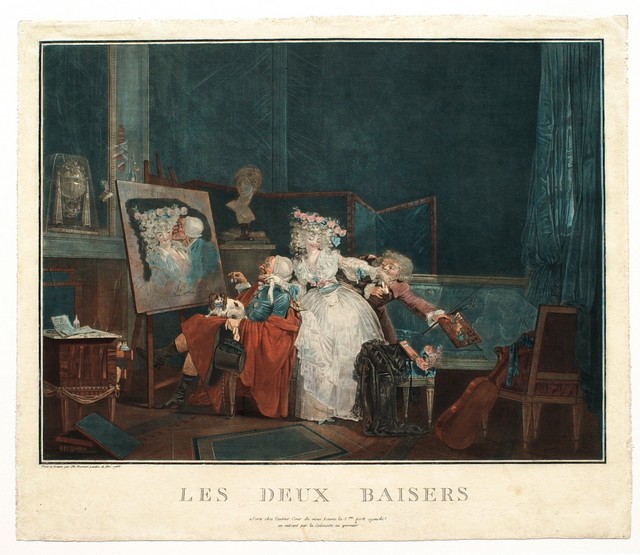

This thesis analyzes representations of women in French artist Philibert Louis Debucourt’s late eighteenth-century fine-art prints (i.e. prints of high cost and quality, often produced by an artist of the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture and occasionally sold via subscription through a print dealer). Though known for his Neoclassical political imagery, the bulk of académie member Debucourt’s printmaking career was dedicated to the reproduction of his own fête galante and domestic genre subjects: an endeavor he continued throughout the 1789 French Revolution. That scholarship involving the revolutionary print market has overlooked these prints in favor of Debucourt’s smaller but more obviously political Neoclassical oeuvre is perhaps due to the perceived rejection of fête galante subject matter (a genre associated with the Rococo style and the aristocracy) by those who came to power at the end of the eighteenth century.

The most prevalent themes of fête galante and domestic genre imagery— women, their social positions, and their experiences of love and relationships– could also be seen as unrelated or unimportant to the political turmoil of the 1789 French Revolution. And yet, the traditional themes found in both genres continued to flourish in print throughout the revolutionary years (though they were often carefully altered by artists in order to evade fines, prison time, or even the guillotine). Debucourt’s fine-art prints and his quick adaptations/alterations of them during the Revolution reveal much about the choices artists made in order to align themselves to revolutionary morality and politics, including the ambiguous and politically-charged debates regarding women’s role as citoyennes of the new French nation. Rather than rejecting artistic styles and subject matter associated to the Ancien Régime, Debucourt used well-known imagery steeped in French traditions– such as the themes, iconography, and settings of fête galante and domestic genre scenes– to express and propagate the ideal of the new citoyenne to those who could afford his fine-art prints. This decision would have secured the artist’s safety during the incredibly hostile political environment of the 1790s while reaching a French public accustomed to particular artistic genres and subjects.

This thesis first contextualizes Debucourt’s artistic choices within the socio-political debates regarding women’s rights and restrictions during the 1789 French Revolution, including the visual manifestations of such debates. It then analyzes Debucourt’s visual construction of the frivolous and nonprocreative elite French woman, the promiscuous and ignorant lower-class woman, and the virtuous wife and mother who embodied the ideal female citizen regardless of class. Ultimately, it argues that Debucourt’s fine-art prints designate power and agency for women within their domestic roles (and occasionally, their sexual relationships) while simultaneously limiting this power via the norms and morals enforced by a political culture seeking to eradicate female presence from the public, political sphere. Unlike prints that circulated the image of the regal Goddess of Liberty (an unobtainable ideal), or the bestial caricatures of women who infiltrated ‘masculine’ political spaces, the politics of Debucourt’s fête-galante and domestic-genre women are subtle. Perhaps the prints’ careful overlay of revolutionary ideals involving the new citoyenne onto ‘traditional’ French imagery was primarily the result of an artist seeking to propagate his work to a particular clientele (likely a middle- to upper-middle class elite who also needed to align to revolutionary ideals and could afford to buy his fine-art prints). Above all, Debucourt’s representation of women during the revolutionary period made a set of culturally authorized female roles designated by a rapidly shifting political and social climate accessible, relatable, and, perhaps, easier to swallow.