Hi! The practicum really flew by!

I am so glad and grateful to have spent the summer working with the University of North Carolina at Gillings Zambia Hub and Dr Stephanie Martin. The practicum focused on analyzing and disseminating data from a formative research project focused on infant care and feeding practices among families affected by Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in Zambia.

The project had conducted qualitative research to examine the feasibility and acceptability of engaging male partners, grandmothers, and other family members to support HIV-positive mothers in Lusaka to practice recommended infant care and feeding practices, and women for continued antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence. The practicum was a wonderful experience that combined my interest in maternal health, child health and Sub- Saharan Africa.

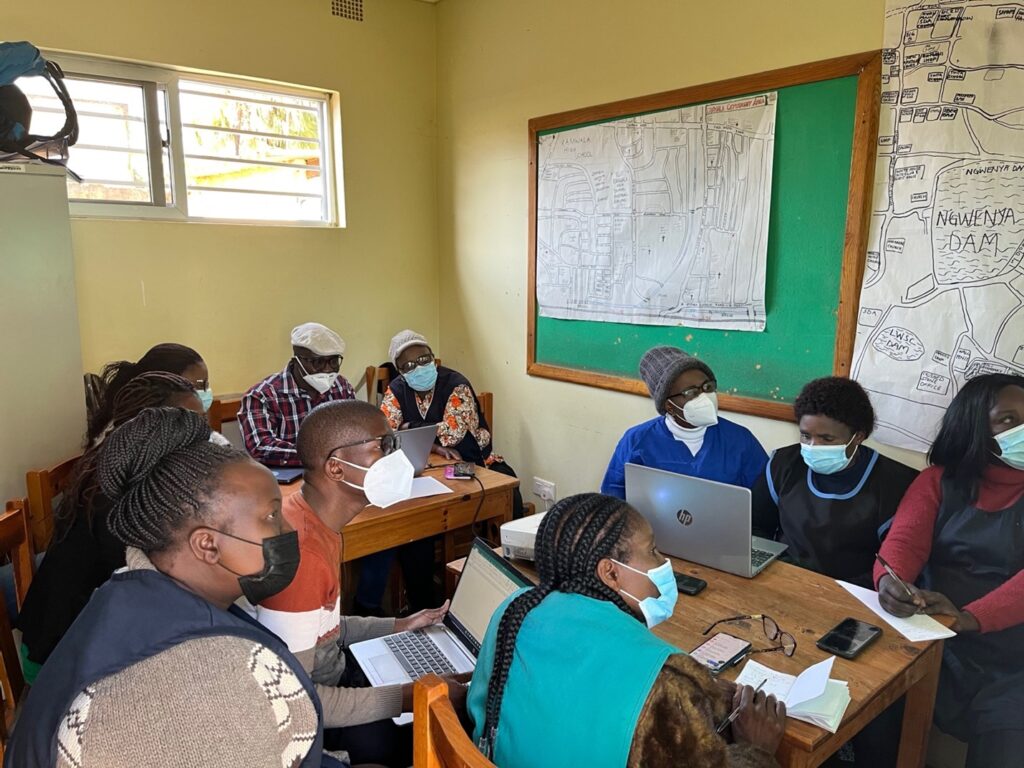

My role involved conducting quantitative analysis of the transcripts of the interviews conducted in Lusaka last summer. I worked using ATLAS.ti software to code the transcripts and create thematic summaries. Though I did not conduct the interviews, it was extremely rewarding to read the impact the education on ART adherence, infant feeding and care had on the study participants. There was marked improvements by the participants in infant health and increased confidence in their ability to care for their infants. Through the summaries, as a team we have been able to identify acceptable and feasible intervention components that will increase ART adherence of people living with HIV and family support with infant feeding and care. I also collaborated with the team to use the organization network analysis software to create descriptive data summaries of the demographics of the interview participants. My preceptor and team members were incredibly supportive in coaching and guiding me on how to use the various analysis software and they helped me work through the challenges of my learning process. This practicum provided me the opportunity to develop tangible skills and work in an interprofessional setting putting to practical use things I have learnt in class.

Before securing a practicum in the spring semester, I was very anxious about finding one and if it will be a good fit. I must say, I am happy with my practicum experience. There is still analysis to do, papers to write and dissemination to undertake on this research, this is a project I would like to be a part of till its completion. Because of this, I have decided to continue my practicum project as an independent study elective during the fall semester.

I genuinely appreciate my preceptors Dr Stephanie Martin and Tulani Matenga and the entire team for their support through out my practicum. I look forward to continuing work with them and providing positive impact in the lives of women living with HIV and HIV exposed-uninfected infants in Zambia and beyond.

– Eni