Last summer was an immersive period of learning and discovery. I had been grappling with a lot of questions around decolonization and localization of global health.

The scars of colonialism in Africa can be found in the profound inequities in healthcare across the African continent. But much has been achieved. And much yet more is desired. To deny the progress made thus far in transforming healthcare across the African continent is shortsighted. But that does not absolve global health policy makers and industry leaders of responsibility to do even more to bridge the inequities.

For context, I would like to highlight the gravity of the issue confronting global health and why decolonization should be reprioritized. As recently as 2020, 85% of global health organizations were headquartered in High-Income Countries (HICs). In these organizations, Diversity, Equity and Inclusion remain elusive as the data show that about 70% of board representations are mostly men (not Black men!), and of the 70% board representation, 80% of them are citizens of HICs and mostly educated in these countries. It doesn’t end there. The real cause of the inequity is in the money and who decides how much should be spent, and where, and at what time, and for which population. Let me give you an example: the funding that goes to local organizations for humanitarian work is less than 2%. USAID awards about 80% of its contracts and grants directly to US organizations. The US and HICs enjoy on average 70% of NIH Fogarty funding grants. Ultimately, this translates to agenda setting by these organizations and micromanagement of global health work even if local institutions have their own expressed health needs and priorities.

Gender parity is critical to global health for the lack of it is a continued symptom of colonization and all the vestiges of privilege. On the gender score, the situation is even more grim with projections that gender parity in global health would remain a mirage until 2074. That is unconscionable. See, while 80% of global health work is in Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs), only 5% of women in these settings are represented in global health work. Meanwhile, women and children constitute the largest population who bear the health burden in this group of countries. Doesn’t it make sense that the people who suffer the inequity most should be given the opportunity to set the agenda and policies regards their own wellbeing?

Doing it the UNC way…

Are there institutions that are championing the change we desire to see in the global health space?

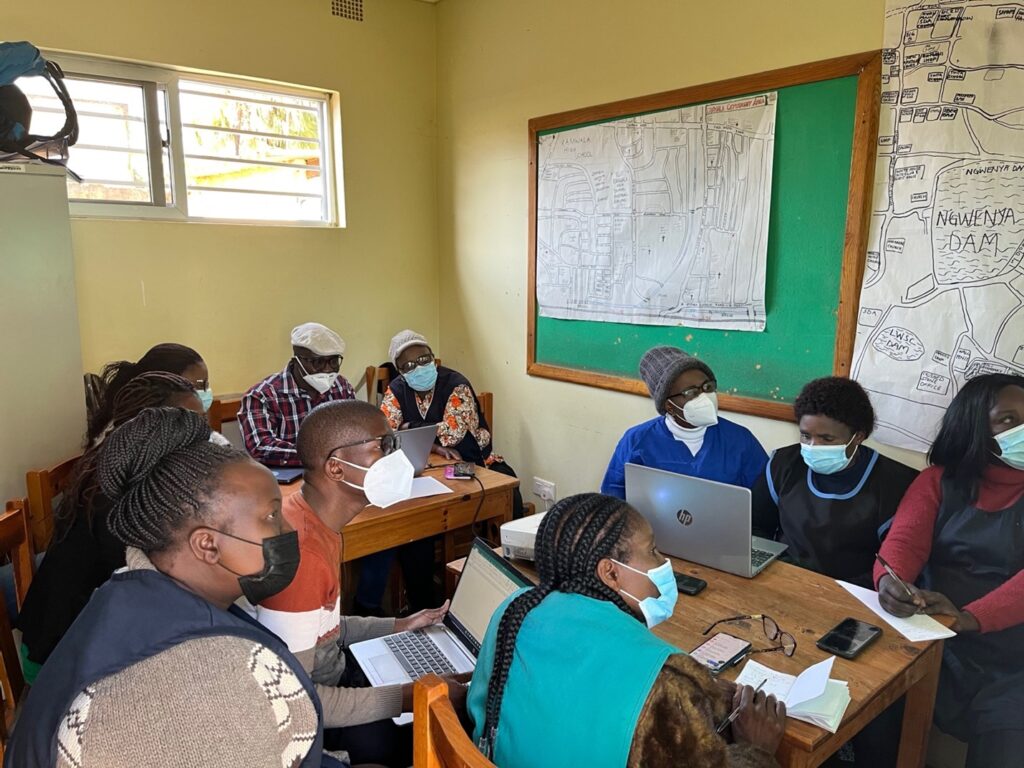

During my summer internship, I worked on an upcoming clinical trial called INSIGHT in Zambia. The Institution—UNC Global Projects Zambia (otherwise called Zambia Hub)— characterized a classic example of how decolonization looks like in some fronts. First, Zambia Hub was established by UNC in Zambia as one of a few centers for global health research in the world. This proofs a point. That global health institutions can also succeed where their services are needed the most. I witnessed how local capacity was strengthened using technology to facilitate inter-institutional learning and capacity development of local staff.

More to it, and even more impressive is the fact that the leadership of Zambia Hub including my own immediate supervisor, research assistants and other support staff were women who constituted the majority of the organization’s workforce. That affirmed something: that women too can run organizations and do so even better if given the opportunity.

I did not do a management audit, nor did I formally interview staff to learn about how the institution was funded and whether locals managed funds, or whether funds were micromanaged from the UNC at Chapel Hill. I am reporting my personal observations about how the setting up of the Zambia Hub and the empowerment of women to run the organization refutes fears I have often heard about mistrust from development partners about the capacity of locals to manage institutions and funds. Zambia Hub, like the rest of the hubs set up by UNC is self-evident and should be sustained.

Going by the hypothesis that decolonization is not an endeavor to take and that it is one that would not yield good returns for donors and funding partners, the success of the Zambia Hub partnership with UNC presents compelling evidence to reject the null for the alternative.

From a global health security standpoint, we all live in thatch houses. And so, when you don’t support your neighbor to put a fire belt around his house, when his house catches fire, your house is next. In other words, I am saying that if we continue to ignore the clarion call to meaningfully decolonize global health, the next bat bite in Africa will cause an outbreak of nose bleeding in the West. Think about it.

While you are thinking about it, I would like to thank Dr. Margaret Kasaro, my preceptor, for her leadership that sees the Zambia Hub grow from strength to strength and proving to the world that yes, locals and women, when given the opportunity can be equal partners in the global health leadership structures and boardrooms. My supervisor, Manze Chinyama, was sterling in her tutelage and experience in all phases of clinical trials and I would like to thank her for her mentorship. To Modesta, the community engagement nonpareil, Laston Zulu, Harold Banda, Chileshe Kasonda, Elizabeth Mubanga and all the Research Assistants I worked with, I want to say thank you for all the support I received during my stay in Zambia.

– Simon