by Michael Baird

“Every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter. The sitter is merely the accident, the occasion. It is not he who is revealed by the painter; it is rather the painter who, on the coloured canvas, reveals himself.”

–Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray

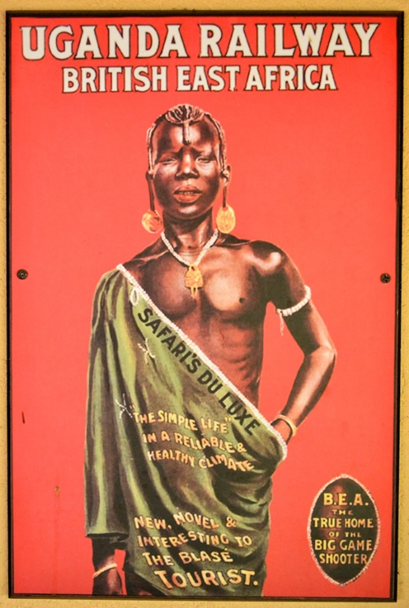

Included in the “General Developments of Interest” report by R. S. Foster, Deputy Director of Education in Uganda, at the 16 February 1939 meeting of the British Advisory Committee on Education in the Colonies, was mention of the “progress in Art work, particularly painting and drawing, under the inspiration of Mrs. Trowell, who worked voluntarily.” He continued by expressing hope that the members of the committee would see for themselves the works produced by Trowell’s students which would be on display at the Imperial Institute in London later that year.[1] As the minutes demonstrate, despite not being employed in a formal capacity within the British colonial bureaucracy, Margaret Trowell came to be understood as not only an asset in the self-proclaimed and, at least partially, rhetorical “civilizing” goals of the British but also in the project of colonial governance more broadly.

Margaret Trowell first arrived in the British East Africa Protectorate in 1929 when her husband, a member of the Colonial Medical Service, was assigned to Kenya. In 1935, he was transferred to Kampala, Uganda, and it was there that—as the story goes—Margaret Trowell began teaching informal art making classes on the veranda of their house.[2] By 1937, her efforts had received sufficient enough attention from the leadership of the protectorate that a fine arts program was incorporated into the curriculum at Makerere University in Kampala, and Trowell, appropriately enough, was selected to be the inaugural director of the program that continues to bear her name.[3] She remained in this role until her retirement and return to England in 1958, splitting her time between the teaching of fine arts classes and curatorial duties at the Uganda Museum, which was, at the time, housed at Makerere.[4]

In the most general terms, this paper seeks to situate the fine arts program at Makerere during the Trowell era within the broader cultural and political context of the British Empire during its final decades of formal control in Uganda. In doing so, I hope to demonstrate that rather than apolitical aesthetic exercises, art education was a key component of the British colonial apparatus. Drawing upon digitized archival materials of the British government, Trowell’s own prolific writings, and secondary literature concerning the history of the program at Makerere, I seek to understand how a white, British-born woman came to be seen as an arbitrator of “authentic” Ugandan and, more broadly, African art; more importantly, however, I seek to turn my attention to the students of Trowell in order to consider how art education shaped the personhood of colonial subjects and how these students and their artistic productions became sites for debates regarding the nature of African personhood. In crafting this impressionistic portrait of the colonial subject-artist in Uganda, the corpus of postcolonial and decolonial thought from both within and without the African continent will prove indispensable. This literature will enable consideration of the psychological dimensions of colonial art education (and an exploration of the limitations of what may be possible in this regard) as well as its political functions, expanding upon the typical emphasis on pedagogy, ideology, and classroom operations that predominates in scholarship on colonial art education.[5]

Culture as an Arena of Colonialism

In his book Decolonizing the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature, Kenyan author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o utilizes martial language to compare the cultural arena of colonialism to more familiar forms of colonial domination. He writes:

The oppressed and the exploited of the earth maintain their defiance: liberty from theft. But the biggest weapon wielded and actually daily unleashed by imperialism against that collective defiance is the cultural bomb. The effect of a cultural bomb is to annihilate a people’s belief in their names, in their languages, in their environments, in their heritage of struggle, in their unity, in their capacities and ultimately in themselves.[6]

He continues by discussing how this alienation from self on the part of the colonized results in an association with their antithesis—the colonizer—and their way of life. His discussion is reminiscent of and, in some ways, an extension of Antonio Gramsci’s conception of cultural hegemony. In “The Intellectuals” and “On Education,” Gramsci argues for the importance of ideology, socialization, and taste to class-based oppression and vertical stratification.[7] The cultivated desire by individuals to achieve the good life as defined by cultural elites facilitates continued exploitation. Thiong’o applies a similar critique to the relationship between colonizer and colonized; the forced alienation from one’s own culture and the simultaneous inculcation of the mores of the metropole subsumes the colonized within the order of the colonizer, creating a system of dependency or “colonization of the mind.”

Similarly, Nigerian novelist and essayist Chinua Achebe argues for the importance of culture as a dimension of the colonial project; however, in his essay “Politics and Politicians of Language in African Literature” published in print in the collection The Education of a British-Protected Child, Achebe rejects the binaries laid out by Thiong’o. Drawing on the historical memory and experience of the Biafran War, Achebe takes issue with the core claim of Thiong’o that the use of English by African writers intrinsically replicates colonial power structures and modes of thinking.[8] For Achebe who comes from a country that does not have a lingua franca with the exception of English and that has experienced first-hand in horrific ways that violence that can occur through the exacerbation of cultural and political cleavages, English cannot simply be said to belong to the English. Culture is not owned but is rather a site of contestation and negotiation. To Achebe, English was a tool of anti-colonial struggle and ongoing nation-building.[9]

The disagreement could possibly be a reflection more of their respective positionality and citizenship than anything else—the existence of Kiswahili as a lingua franca in the area that constitutes the modern day nation-state of Kenya provided a readymade alternative for Thiong’o’s call for continued anti-colonial efforts—and a warning against the tendency for generalization that flattens the unique historic experiences of colonialism and possibilities for the postcolonial even amongst formerly British colonies on the African continent. Certainly, both Thiong’o and Achebe understand culture as an important arena of the colonization and the fight against it. The instrumentalization of culture—specifically language, dress, art, literature, and even architecture—by post-independence state builders in Africa like Mobutu Sese Seko in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) and Léopold Sédar Senghor in Senegal illustrate the pivotal role of culture in continued agitation against what could be understood as the vestiges and continuing forms of colonialism.[10]

The Artist is not Present

Margaret Trowell begins her article “The Kampala Art Exhibition—A Uganda Experiment” with what seems to be a rather bold claim, albeit one that typifies the attitude in the United Kingdom at the time. She writes, “At first glance East Africa is probably one of the most disappointing parts of the world from the point of view of the student of indigenous art.”[11] She goes on to juxtapose this vacuum with the recognized sculptural canon of art that emerged from West Africa.[12] The representational, incredibly high relief forms of—for example—the so-called “Benin Bronzes” more readily aligned with European constructions of “fine art.”[13] Three dimensional, optically real art works depicting subject matter with human figures were well represented within the canon of European art history from its fabricated origins in the Greco-Roman world and also able to be rendered knowable and legible through the methodologies of art historical inquiry.

With the exception of isolated groups of works like the Benin Bronzes—regardless of the provisionality of their positioning within the category of art—sub-Saharan Africa was understood by Europeans to be devoid of art. Western understandings of art and what kinds of material culture were encompassed by that term were, and often still are, taken as natural, given, and universal. So too are the attendant hierarchies that privilege the so-called fine arts of sculpture and painting as well as the favored mimetic genres. According to the suppositions of evolutionist thought, the lack of art on the African continent was evidence of the inferiority of African populations, which were understood to be at an earlier point on the teleological timeline of human evolutionary “progress.”

As Aníbal Quijano points out, it was the Europeans—the very people situating themselves at the endpoint of the timeline they were producing—that were setting the rubrics and classificatory schemes by which culture was measured. He writes, “Through the political, military and technological power of its foremost societies, European or Western culture imposed its paradigmatic image and its principle cognitive elements as the norm of orientation on all cultural development, particularly the intellectual and the artistic.”[14] Addressing the African continent specifically, he continues, “What the Europeans did was to deprive Africans of legitimacy and recognition in the global cultural order dominated by European patterns.”[15]

As they become naturalized, categories and labels like art gain what seems to be a rationality or internal logic of their own, despite the reality that this production of knowledge is, by necessity, situated.[16] The presumed universality of that which arose out of a particular social and cultural context—regardless of how fictional—has material effects. The global distribution of what came to be called art divided the world and provided a rhetorical justification and impetus for colonial rule and, more specifically, for educational projects like that of Trowell in Uganda.

African Artist as Medieval European

Even as an agent of the European global effort of remaking the world in its own cultural image, Margaret Trowell espoused a broader definition of art than many of her contemporaries. The title of her first book, African Arts and Crafts: Their Development in the School, published in the same year that she became director of the fine arts program at Makerere, is instructive; she did not see the African continent or even East Africa as devoid of art and certainly not devoid of the potential for further production of art and refinement of existing practices, which was the cause to which she dedicated her career in this period.[17] In African Arts and Crafts, she offers a definition of art that challenges the binary of art/craft and the presumed hierarchy associated with the two. While art was often seen as—and continues to be, in some cases—the prerogative of the white male genius artist who is presumed to be intellectually engaged with art history and theory, craft was positioned as its antithesis. Craft was and is a highly gendered and racialized category associated with the “primitive,” rote adherence to tradition, and more corporal than intellectual engagement.[18]

Trowell does not so much discard the categories of art and craft in their entirety but rather expand the category of art to include types of material culture often placed within the category of craft. She writes, “By art I think we should mean all worthy handicraft, from daily work and ploughing to cathedral building…art may seem a subject remote from many…but I wish to argue…[art] is near every one of us. It is universal and for all.”[19] In doing so, she seeks to elevate craft to the status of art and grant it the relative prestige reserved typically for art.

To understand Trowell’s views on what art is, it is necessary to consider her educational history and intellectual influences. Before she was an art educator, she was an artist herself; she attended the Slade School of Fine Art, University College London from 1924-1926. After recognizing her interest in art education, she enrolled at London University Institute of Education. There she was a student of Marion Richardson—a British educator and author who was known for her approaches to teaching art making and handwriting to school-age children—who had an indelible impact of Trowell’s educational philosophy and understanding of art. Richardson emphasized giving children the space to develop their artistic practices on their own terms, at least in theory.[20] Juxtaposed with the technical exercises and emphasis on the copying of old “Masters” inherited from the Academic system, this philosophy was quite radical.

While it is true that Richardson’s approach, at least arguably, granted children more autonomy and agency, its underlying rationale was steeped in primitivist and even evolutionist logic. Richardson was interested in what she understood to be the “purity” of art produced by those who were understood to be on the margins of or most untouched by society. To her the works of children, the incarcerated, and the mentally ill, especially when their natural development was not hindered by external societal interventions, was an art that was more pure and more human. Not only does this understanding require, by necessity, a biopolitical division of humanity that is then naturalized and supposedly evidenced (tautologically) by the art produced, but it also requires the presumption that a natural state of humanity exists and that some individuals are less developed and, therefore, closer to that point.

At the same time that Trowell was studying under Richardson, the British Arts and Crafts Movement, although certainly past its apogee, was still a major cultural force. Although there was quite a bit of diversity of thought among its key proponents, in general, the Arts and Crafts Movement could be understood as a reaction to modernity, industrialization, and even the Enlightenment more broadly. For figures like John Ruskin and William Morris, the antithesis to the ailments of modern means of production was medieval Europe.[21] For Ruskin and Morris, medieval Europe, especially as exemplified by the Gothic cathedral, represented a time when humanity was closer with nature, craftspeople were closer to their work which may continue for multiple generations and did not involve factory methods of production, and the Enlightenment emphasis on rationality had not foreclosed the possibility of transcendent experience. Unsurprisingly, their view of the medieval period was romantic and ahistorical and said more about the period in which they were writing and their thoughts about it than any empirical reality of the medieval period.

The symbol of the medieval European craftsperson was a recurring theme in Trowell’s writings on Ugandan artists.[22] At various points, this was a reflection of reality as she saw and understood it or more of an aspirational model that she hoped to cultivate through her art education program. For Trowell, the medieval European functioned similarly to how it did for Ruskin and Morris. She saw in her students, and in African populations more broadly, the potential for art to continue existing alongside and inextricable from life itself, as opposed to the European modernist tenets of “art for art’s sake.”[23] In her mind, the African artist was free from the trappings of mechanization and individualism and was, therefore, producing art that was more “pure.” British-Ugandan artist and art historian Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa points to an additional function of this image of the medieval craftsperson in the imagination of Trowell. She argues that, in a way that was not necessarily the case for figures like Ruskin and Morris, Trowell also desired a return to what she perceived of as the intensity of religious piety during the medieval period.[24] For Trowell, art education was not and should not be separated from missionary efforts.

This marking and fetishization of difference between colonist and colonial subject—whether it be through the image of the child or that of the medieval European craftsperson—created the impression that somehow Trowell’s students were outside of modernity and time itself. It reinforced European evolutionist narratives of linear and teleological progress with African individuals positioned behind Europeans, either as not fully developed (children) or mythic but historical previous Europeans (the romanticized and exoticized image of the imagined medieval craftsperson.)[25] The ambiguous and, at times, seemingly contradictory relationship of Trowell to her students illuminates what could possibly be considered the central paradoxes of the British “civilizing mission”: Namely, the need to continually mark difference between the colonizer and colonized precluded accomplishment of the rhetorical goals of civilizing efforts. In other terms, if the stated aim to civilize was successful, it would have obviated the legitimizing rationale of colonial relations. Additionally, Trowell’s belief in the British obligation to assist in the evolutionist development of African populations was fundamentally at odds with her desire to maintain the purity of African art and the relationship between Africans and material culture.

An “Authentically” African Artist

The students at Makerere and the art works that they produced became arenas in which British colonial officials and intellectuals debated these theories and apparent contradictions. Writing about this time period in the British colonies where indirect rule was being more widely adopted in places like the Uganda and during which the end of British control in some parts of the world started to seem like less of an incredibly distant prospect, art historian Sunanda K. Sanyal argues, “It was no secret in this era that Makerere had been a pawn in the protectorate administration’s experiments with education.”[26] He goes on to outline some of the different factions within the Western faculty at Makerere. On one hand were those who adhered to strict evolutionist thinking. If Ugandan students were simply at an earlier stage in the process of human development, then a curriculum that mirrored British educational institutions was ideal. For Trowell and others who espoused the so-called “Adaptation Theory,” there was a belief that there were cultural distinctions between Europeans and Africans and that the best curriculum for the university would consider and incorporate both.[27] While in theory this view left space for alternative forms of knowledge production and challenged the presumed universality of Western thought, it relied upon an essentialist view of culture that, in practice, revealed more about the British image of Africa than truly emic forms of knowledge production. In other words, cultural relativity did not equate to cultural pluralism or equality, especially in a colonial context where power in its various manifestations was so asymmetrically distributed.

As a proponent of Adaptation Theory and, furthermore, as someone who believed and valued the supposed purity of African art, Trowell wrote extensively about the need to maintain the African nature of the work of her students. Ideally, education would permit the students to “adapt” the useful elements of European thought while developing according to the lines of their essential cultural characteristics.[28] To this end, Trowell discusses her exhaustive efforts to limit the exposure of her students to Western fine art and reproductions. She also insisted on a bottom-top approach in the classroom, arguing that she had minimal influence on the works of her students; she went so far as to famously give up her artistic practice during periods of her time as director of the fine arts program at Makerere as to not affect unduly the work of her students.

Taking her statements of wanting to maintain the African-ness of the works of her students at face value, one might expect to see students working in any of the media—for example, basketry, decorated gourds, body adornments, or musical instruments—and/or adopting the subjects or forms of any of the Ugandan material culture Trowell exhaustively surveys in African Arts and Crafts or Tribal Crafts of Uganda.[29] Up until this point, I have only seen evidence of her students working in two-dimensional media, painting and printmaking, as well as sculpture of which there is no evidence for longer lineage in Uganda.

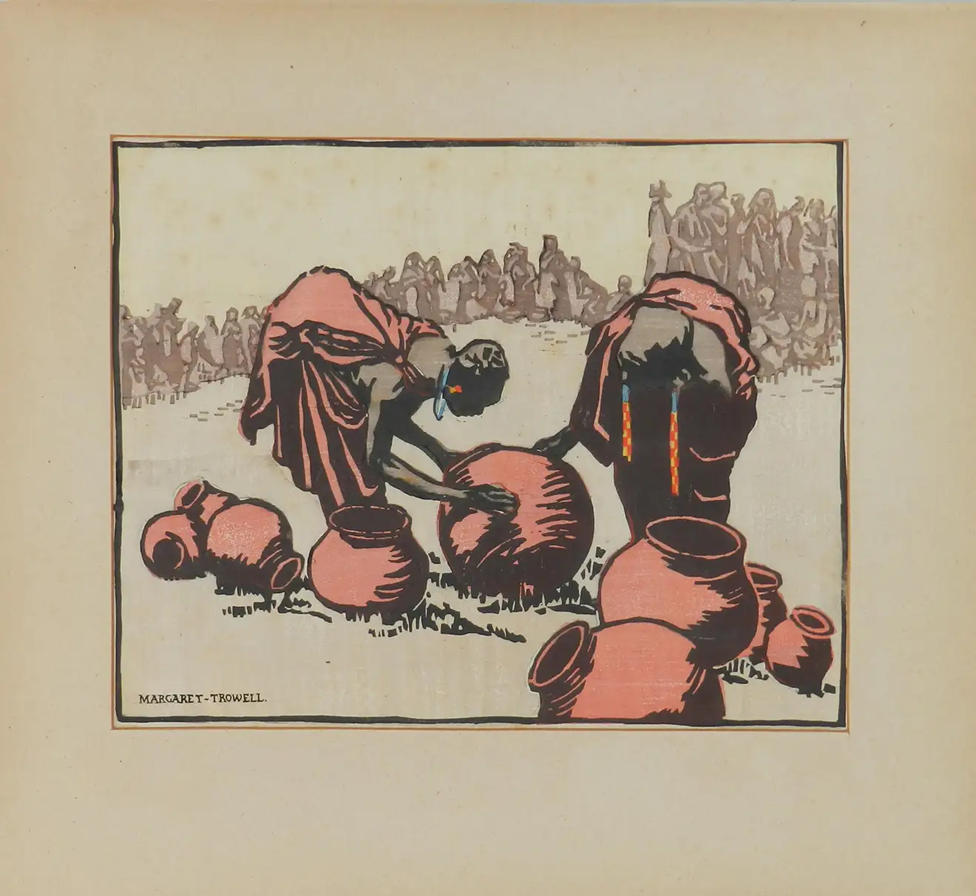

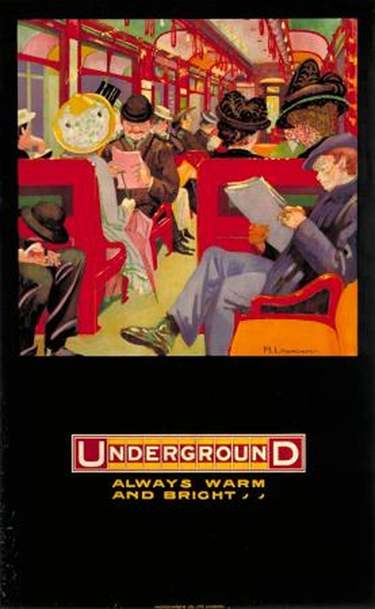

It is instructive to pause for a moment and consider a print by Trowell herself. (Figure 1) The image depicts two black women bending over in order to—it seems—scrutinize a pot that is in the central focal point of the composition. The figure on the left is in a profile view while the one on the right is in a frontal view, but the both their faces are inscrutable, submerged almost completely into shadow. In the distant background are gently rolling hills upon which undifferentiated and anonymous masses of people stand. The scene calms; it is pastoral and idyllic and the labor of the women, if that is what is occurring, is represented as leisurely contemplation. Without an ability for the viewer to discern the faces of the main figures, they seem to function more as passive objects for consumption by the colonial gaze than subjects capable of returning that gaze. The color of their clothing and the dramatic shading echoes the forms of the vessels scattered on the ground, which themselves follow the same diagonal across the picture plane as the anonymous masses behind.

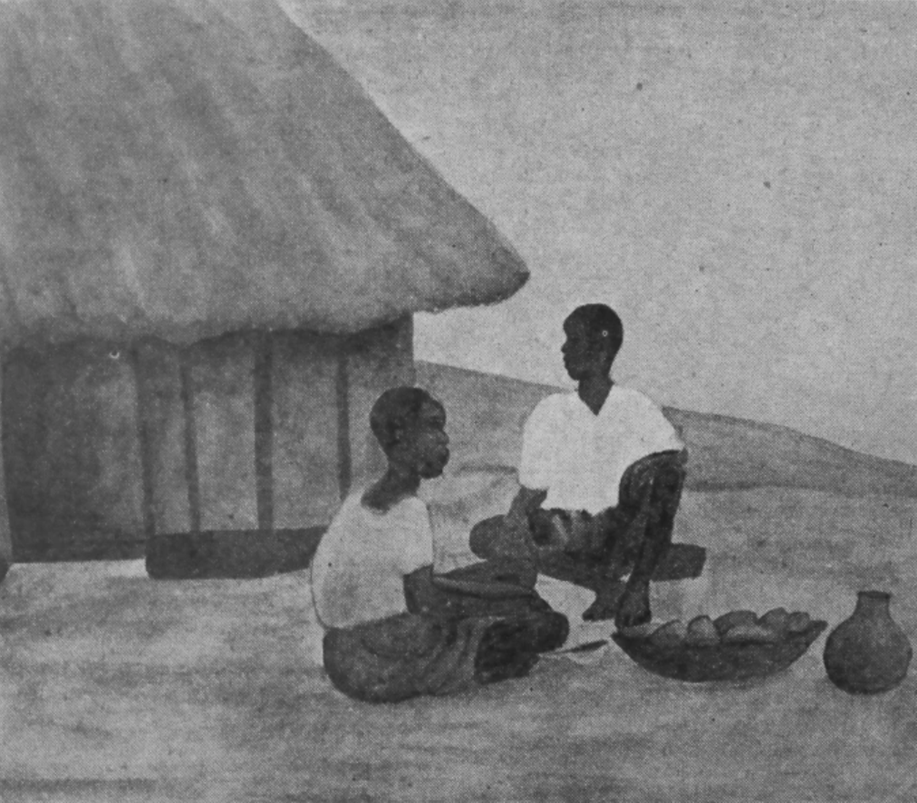

A comparison with the work of one of her students that she published to illustrate a 1947 essay in the journal Man is provocative.[30] (Figure 2) Appropriately enough, she did not attribute the work.[31] Even without access to the coloring of the original (if it is even still extant,) parallels can still be drawn in terms of the rural subject matter and anonymous figurative forms positioned alongside material culture that would have been recognizable, in a general sense, to Western audiences. Despite (or more accurately perhaps, because of) her stated desire to facilitate growth of Ugandan art along its own lines, preserving its essential African nature, the images of Africa produced by her students seem to replicate Trowell’s own essentialized and stereotypical view of Africa and its peoples. She positioned herself as the arbitrator of authentic African-ness and, unsurprisingly perhaps, saw her ideas of African reflected back at her from the picture planes of her students.

It was these kinds of images that found a market in the West and that received the approval of colonial officials like Trowell. To Western eyes, these were authentic representations, because they conformed to the images that Europeans already had in their minds. In Orientalism, Edward Said discusses how the marginalized can psychologically internalize both discursive and visual representations of themselves.[32] At Makerere, Ugandan artists were not only looking at and consuming exoticizing and primitivizing images but producing them. And finding success within the liberal and capitalist hegemonic colonial order through it.[33]

Can the African Artist Speak? Further Directions

Despite Margaret Trowell’s claim that she wanted to minimally interfere with the work of her students, she was the ultimately authority within the classroom and a privileged based on her nationality and ability to navigate the cultural spheres of the metropole and the Ugandan colony. As already noted, her draconian limits on what was acceptable for her students to be exposed to and draw inspiration from insured that she was herself playing a role in maintaining the contours of what may be artistically possible for her students. It also presumed that Uganda and its peoples had not been an active and connected part of the international system before the arrival of the British in a sustained way. As Quijano notes, Trowell had the full weight of the military and economic power of the colonial United Kingdom to enforce her cultural vision, her cultural values, and to set the terms of engagement.[34]

Given this fact, what, if anything, can a historian say about the students on their own terms? What can be recovered? This portrait of the Ugandan artist at Makerere during the Trowell era, perhaps by necessity, reveals more about British concerns and anxieties—about their supposed cultural superiority and the universality of their cultural rubrics, about the impact of modernity and mechanization on material culture, about the tenuousness of their colonial rule, about their images of themselves and the African continent—than any reality of the African continent or its peoples.

In her famous essay, “Can the Subaltern Speak?” Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak urges caution in attempting to recover the voices of the already marginalized, lest one perpetuates another level of violence; another act of silencing built on historical acts of silencing.[35] Is there a way to avoid simply projecting the anxieties and debates of my current moment into my images of Trowell’s students at Makerere? To avoid reading agency where there is none or where it would not have been conceived of in that way by the individuals themselves?

US American writers Simon Gikandi and Saidiya Hartman, in “Rethinking the Archive of Enslavement” and “Venus in Two Acts,” respectively, provide alternative ways of engaging with the archive that may prove useful in considering the students at Makerere in their own terms. Gikandi proposes the reading the archive, which is itself a testament of the power of hegemonic forces, for slippages and secondary narratives that reveal lived realities of those who are not the authors of the archive.[36] Hartman pushes the possibility of the archive perhaps a bit further, arguing for paint[ing] as full a picture of the lives” of marginalized individuals featured within the archive by “exceed[ing] or negotiat[ing] the constitutive limits of the archive…by advancing a series of speculative arguments and exploiting the capacities of the subjunctive.”[37]

If the subaltern cannot speak, can they at least make noise? Could the strength of that noise be its illegibility?[38] Its inability to be captured, fixed, subsumed within the presumed universal epistemological confines of knowledge production deriving from the Western Enlightenment? In his provocatively titled “Can the Mosquito Speak?” Timothy Mitchell raises the question as to whether nonhumans can be agents of history.[39] Could the artworks produced by Trowell’s students speak? Were they agents in the history of colonialism? Do they continue to be?

In her autobiography, African Tapestry, published the year before she left Uganda to return to the United Kingdom, Margaret Trowell writes about her experiences with one student, Gregory Maloba.[40] For his part, Maloba would ultimately become a fairly well-renowned sculptor in East Africa. For instance, his work still remains in the permanent collection of the Uganda National Museum. In the passage, Trowell emphasizes—a position that she often adopts in her writing—the great efforts and lengths that she went to in order to reduce exposure of her students to what she understood as external influences. She employs the anecdote to highlight her sacrifice with the goal of cultivating a kind of sympathy in the reader for her, but, regardless of the veracity, might we understand the narrative in a different light?

In the text, she recounts how despite her best efforts to keep Maloba from reproductions of canonical and contemporary European art, she found him one day having snuck into her personal library in her house while she was away. According to her, he was there to look at her books of European art history. For Trowell, this was a source of endless frustration as she so desperately sought what did not exist in reality but was a product of her mind, her own fictional image of the African artist. Instead of loss, perhaps we might see resistance. We might see an African artist, as modern and as contemporary as everyone around him, navigating a highly asymmetrical colonial structure, adopting what is useful and disregarding what is not.

Might there be other Gregorys?

[1] “Minutes of the Ninety-First Meeting of the Advisory Committee on Education in the Colonies,” Advisory Committee on Education in the Colonies: Minutes of 15th-95th Meetings, 1939, 6.

[2] Margaret Trowell, African Tapestry (London, United Kingdom: Faber and Faber, 1957), 103.

[3] Elisbeth Joyce Court, “Margaret Trowell and the Development of Art Education in East Africa,” Art Education 38, no. 6 (1985): 35–41.

[4] This antecedent to the Uganda National Museum was moved to its current location on Kitante Hill in Kampala in 1954.

[5] For instance, see Hamid Irbouh, Art in the Service of Colonialism: French Art Education in Morocco, 1912-1956 (London, United Kingdom: I.B. Tauris, 2012); J.P. Odoch Pido, “Pedagogical Clashes in East African Art and Design Education,” Critical Interventions 8, no. 1 (2014): 119–32; and Sunanda K. Sanyal, “Modernism and Cultural Politics in East Africa: Cecil Todd’s Drawings of the Uganda Martyrs,” African Arts 39, no. 1 (Spring 2006): 50–59.

[6] Ngũgĩ wa Thiongʼo, Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature (London, United Kingdom and Portsmouth, New Hampshire: James Currey Ltd. and Heinemann, 1986), 3.

[7] Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, trans. Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith (London, United Kingdom: Lawrence and Wishart, 2003), 3-43.

[8] Chinua Achebe, “Politics and Politicians of Language in African Literature,” in The Education of a British-Protected Child (New York City, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009), 96–106.

[9] Ibid.

[10] For an overview of Mobutu Sese Seko’s policy and state-sponsored program of Authenticité, see Sarah Van Beurden, Authentically African: Arts and the Transnational Politics of Congolese Culture (Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2015). On the École de Dakar and twentieth-century art in Senegal in the decades following Léopold Sédar Senghor’s time as president, see Elizabeth Harney, In Senghor’s Shadow: Art, Politics, and the Avant-Garde in Senegal, 1960-1995 (Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2004).

[11] Margaret Trowell, “The Kampala Art Exhibition—A Uganda Experiment,” Oversea Education: A Journal of Educational Experiment and Research in Tropical and Subtropical Areas 10, no. 3 (April 1939): 131.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Though it should be said that the status of the Benin Bronzes as art—while more widely agreed upon at the time of Trowell’s writing—was relatively recent. In the proceeding decades, debates raged as to how they should be considered and even as to their origins (attributed variously to Egypt or waves of migration from the north,) with some scholars expressing skepticism that they could have been the artistic productions of sub-Saharan Africans. For this history, see Annie Coombes, Reinventing Africa: Museums, Material Culture and Popular Imagination in Late Victorian and Edwardian England (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1994).

[14] Aníbal Quijano, “Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality,” Cultural Studies 21, no. 2–3 (2007): 170.

[15] Ibid, 170.

[16] Timothy Mitchell, Rule of Experts: Egypt, Techno-Politics, Modernity (Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 2002), 13-15.

[17] Margaret Trowell, African Arts and Crafts: Their Development in the School (London, United Kingdom: Longmans, Green and Co., 1937).

[18] The art/craft binary mirrors the relative privileging of mind over body within Cartesian dualism. On the implications of normative dualism, see Alison M. Jaggar, Feminist Politics and Human Nature (Totowa, New Jersey: Rowman and Allanheld, 1983).

[19] Trowell, African Arts and Crafts, 33.

[20] Marion Richardson, Art and the Child (London, United Kingdom: University of London Press, 1948); Rosemary Sassoon, Marion Richardson: Her Life and Her Contribution to Handwriting (Bristol, United Kingdom: Intellect Books, 2011).

[21] See John Ruskin, The Stones of Venice, 2nd ed. (London, United Kingdom: Smith, Elder, and Company, 1867). For a general introduction to the Arts and Crafts Movement, see Elizabeth Cumming and Wendy Kaplan, The Arts and Crafts Movement (New York City, New York: Thames and Hudson, 1991).

[22] Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa, “Margaret Trowell’s School of Art or How to Keep the Children’s Work Really African,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Race and the Arts in Education, ed. Amelia M. Kraehe, Ruben Gaztambide-Fernandez, and B. Stephen Carpenter (London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 85–101.

[23] Frequently, Trowell in her writings would easily slip between specifics and generalizations. She did not hesitate to philosophize on African nature and African art more broadly. This reductionist and totalizing tendency is perhaps not surprising and is part of the larger colonial image of the continent, but it should be said that this elision is hers and not one that I am making.

[24] Ibid.

[25] On “colonial difference,” see Partha Chatterjee, The Nation and Its Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial Histories (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1993).

[26] Sunanda K. Sanyal, “Modernism and Cultural Politics in East Africa: Cecil Todd’s Drawings of the Uganda Martyrs,” African Arts 39, no. 1 (Spring 2006): 51.

[27] Ibid, 51-56.

[28] Sanyal and Wolukau-Wanambwa.

[29] Trowell, African Arts and Crafts: Their Development in the School; Margaret Trowell and K.P. Wachsmann, Tribal Crafts of Uganda (London, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 1953).

[30] Margaret Trowell, “Modern African Art in East Africa,” Man 47 (1947): 1–7.

[31] The question of anonymity in the reception of African art in the West has been the subject of important studies, especially regarding the intentional obfuscation of authorship to conform to Western perceptions of African art. Investigation of naming practices in the fine arts program at Makerere though remains fertile ground for future exploration. See, for instance, Sidney Littlefield Kasfir, “One Tribe, One Style? Paradigms in the Historiography of African Art,” History in Africa 11 (1984): 163–93.

[32] Edward Said, Orientalism (New York City, New York: Vintage Books, 1978), 25-28.

[33] The role of art in relation to the colonial, capitalist international system also merits further exploration. In their seminal essay for critical museum studies, “The Universal Survey Museum,” Carol Duncan and Alan Wallach highlight how perceptions of fine art erase or mystify the accumulation of labor that produces it and how myth of the creative genius reinforce meritocratic ideals. The overlap between these values and the liberal ideology that fueled colonialism and the expansion of Western hegemony seems significant to consider in the context of colonial art education. Carol Duncan and Alan Wallach, “The Universal Survey Museum,” Art History 3, no. 4 (1980): 448–69.

[34] Quijano, 2-3.

[35] Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Can the Subaltern Speak?,” in Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory: A Reader, ed. Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman (New York City, New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), 66–111.

[36] Simon Gikandi, “Rethinking the Archive of Enslavement,” Early American Literature 50, no. 1 (2015): 81–102.

[37] Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (June 2008): 11.

[38] Fred Moten, “Resistance of the Object: Aunt Hester’s Scream,” in In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 1–24.

[39] Mitchell, Rule of Experts: Egypt, Techno-Politics, Modernity, 19-53.

[40] Margaret Trowell, African Tapestry (London, United Kingdom: Faber and Faber, 1957), 104.

Bibliography

Achebe, Chinua. “Politics and Politicians of Language in African Literature.” In The Education of a British-Protected Child, 96–106. New York City, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009.

Chatterjee, Partha. The Nation and Its Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial Histories. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1993.

Coombes, Annie. Reinventing Africa: Museums, Material Culture and Popular Imagination in Late Victorian and Edwardian England. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1994.

Court, Elisbeth Joyce. “Margaret Trowell and the Development of Art Education in East Africa.” Art Education 38, no. 6 (1985): 35–41.

Cumming, Elizabeth, and Wendy Kaplan. The Arts and Crafts Movement. New York City, New York: Thames and Hudson, 1991.

Duncan, Carol, and Alan Wallach. “The Universal Survey Museum.” Art History 3, no. 4 (1980): 448–69.

Gikandi, Simon. “Rethinking the Archive of Enslavement.” Early American Literature 50, no. 1 (2015): 81–102.

Golant, William. Image of Empire: The Early History of the Imperial Institute, 1887-1925. Exeter, United Kingdom: University of Exeter, 1984.

Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Notebooks. Translated by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. London, United Kingdom: Lawrence and Wishart, 2003.

Harney, Elizabeth. In Senghor’s Shadow: Art, Politics, and the Avant-Garde in Senegal, 1960-1995. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2004.

Hartman, Saidiya. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (June 2008): 1–14.

Irbouh, Hamid. Art in the Service of Colonialism: French Art Education in Morocco, 1912-1956. London, United Kingdom: I.B. Tauris, 2012.

Jaggar, Alison M. Feminist Politics and Human Nature. Totowa, New Jersey: Rowman and Allanheld, 1983.

Kasfir, Sidney Littlefield. “One Tribe, One Style? Paradigms in the Historiography of African Art.” History in Africa 11 (1984): 163–93.

“Minutes of the Ninety-First Meeting of the Advisory Committee on Education in the Colonies.” Advisory Committee on Education in the Colonies: Minutes of 15th-95th Meetings, 1939, 6.

Mitchell, Timothy. Rule of Experts: Egypt, Techno-Politics, Modernity. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 2002.

Mitchell, Timothy. Rule of Experts: Egypt, Techno-Politics, Modernity. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 2002.

Moten, Fred. “Resistance of the Object: Aunt Hester’s Scream.” In In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition, 1–24. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2003.

Pido, J.P. Odoch. “Pedagogical Clashes in East African Art and Design Education.” Critical Interventions 8, no. 1 (2014): 119–32.

Quijano, Aníbal. “Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality.” Cultural Studies 21, no. 2–3 (2007): 168–78.

Richardson, Marion. Art and the Child. London, United Kingdom: University of London Press, 1948.

Ruskin, John. The Stones of Venice. 2nd ed. London, United Kingdom: Smith, Elder, and Company, 1867.

Said, Edward. Orientalism. New York City, New York: Vintage Books, 1978.

Sanyal, Sunanda K. “‘Being Modern’: Identity Debates and Makerere’s Art School in the 1960s.” In A Companion to Modern African Art, edited by Gitti Salami and Monica Blackmun Visona, 255–75. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 2013.

Sanyal, Sunanda K. “Modernism and Cultural Politics in East Africa: Cecil Todd’s Drawings of the Uganda Martyrs.” African Arts 39, no. 1 (Spring 2006): 50–59.

Sanyal, Sunanda K. “Modernism and Cultural Politics in East Africa: Cecil Todd’s Drawings of the Uganda Martyrs.” African Arts 39, no. 1 (Spring 2006): 50–59.

Sassoon, Rosemary. Marion Richardson: Her Life and Her Contribution to Handwriting. Bristol, United Kingdom: Intellect Books, 2011.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” In Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory: A Reader, edited by Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman, 66–111. New York City, New York: Columbia University Press, 1993.

The College of Engineering, Design, Art and Technology: Makerere University. “The Makerere Art School Through The Ages.” Accessed December 8, 2021. https://cedat.mak.ac.ug/academics/schools/mtsifa/the-makerere-art-school-through-the-ages/.

Thiongʼo, Ngũgĩ wa. Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature. London, United Kingdom and Portsmouth, New Hampshire: James Currey Ltd. and Heinemann, 1986.

Trowell, Margaret, and K.P. Wachsmann. Tribal Crafts of Uganda. London, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 1953.

Trowell, Margaret. “Modern African Art in East Africa.” Man 47 (1947): 1–7.

Trowell, Margaret. “The Kampala Art Exhibition–A Uganda Experiment.” Oversea Education: A Journal of Educational Experiment and Research in Tropical and Subtropical Areas 10, no. 3 (April 1939): 131–35.

Trowell, Margaret. African Arts and Crafts: Their Development in the School. London, United Kingdom: Longmans, Green and Co., 1937.

Trowell, Margaret. African Design: An Illustrated Survey of Traditional Craftwork. 2nd ed. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 2003.

Trowell, Margaret. African Tapestry. London, United Kingdom: Faber and Faber, 1957.

Trowell, Margaret. African Tapestry. London, United Kingdom: Faber and Faber, 1957.

Trowell, Margaret. Classical African Sculpture. 3rd ed. London, United Kingdom: Faber and Faber, 1970.

Van Beurden, Sarah. Authentically African: Arts and the Transnational Politics of Congolese Culture. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2015.

Wolukau-Wanambwa, Emma. “Margaret Trowell’s School of Art or How to Keep the Children’s Work Really African.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Race and the Arts in Education, edited by Amelia M. Kraehe, Ruben Gaztambide-Fernandez, and B. Stephen Carpenter, 85–101. London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.