By Jaylon Crisp

Introduction

In today’s world economy, more than 45% of the world’s supply of cocoa used in chocolate products comes from Côte d’Ivoire, also known as the Ivory Coast, with about 70% sourced from the associated West African region. However, out of the estimated 100 billion in revenue made by the chocolate industry, the producers of Ivory Coast only receive around 4% of the capital gains. The average paid cocoa worker only receives the equivalent of $0.78 for a day’s work (Collins 2022). Despite the efforts of the Ivorian government, a combination of lobbying, government corruption, and outsourcing to other cocoa producers, allows the chocolate industry to make maximum profits at the expense of the cocoa workers. To compensate for the decreasing returns, cocoa farmers turn to one of the most questionable forms of labor: children.

Child laborers are often a mix of orphans, the children of other cocoa workers, or slaves sold to plantations. With little to no compensation, Ivorian kids face long work hours and, in some circumstances, dangerous work conditions (Busquet et al. 2021). At the surface level, it may seem that the Ivorian families and farmers are to blame for allowing such a heavily taboo practice in their work. However, to understand why child labor is so common in the West African cocoa industry, one must understand the bigger picture that Ivory Coast is a part of, from the colonial past of chocolate to the globalizing market of the 1950’s and beyond. Once the power dynamics of the Ivory Coast are better understood, then it may be more clear why the farmers make so little and child labour is so common.

Historical Background: Slavery, the Colonial Transition, and a Postcolonial Market

Originally, cocoa trees were once only native to South America, but during the 19th century, cocoa trees were first introduced to West Africa with Portuguese plantation owners bringing the plant to the islands of Principe and São Tomé. These islands would be the origins of the cocoa suppliers we know today. Plantation owners forced many Africans into legal forms of slavery, forcing the slaves into living in small huts on the islands. In 1876, the cocoa plant was brought to mainland Ghana, a neighboring country to the Ivory Coast. (Saripalli 2021). During the colonial period of Ghana, the country was inhabited not only by the British colonists, but German missionaries and entrepreneurs as well. The cocoa plants initially thrived in the hot tropical weather, and the beginning of a new colonial trade empire began. In the following years, cocoa production would establish a booming cocoa trade akin to the one established in South America, leading to the spread of cocoa throughout the coastal West African countries.

As the main cocoa producing country shifted from Ghana to the Ivory Coast in the 1920’s, eurocentric-origin chocolate confectionary companies became exponentially richer due to more availability of cocoa, along with the colonists that ran the trade. Like other colonized nations though, the indigenous laborers of the Ivory Coast made considerably lower wages than the middle men and chocolate manufacturers of the trade operation. During the mid-20th century, the postcolonial wave would strike the shores of West Africa, eventually leading to the independence of the Ivory Coast in 1960. Along with this freedom came the liberation of the colonial cocoa plantations, now mostly under the control of the Ivorian citizens (Ludlow 2012). Futures were looking hopeful for the African nation, as a new government established a communal-style tenure system to cocoa production, a model which would lead to Ivorian farmers earning a much larger sum from their harvests. As the country shifted from colonial to postcolonial, so too did the power dynamics that controlled the cocoa market. Power went from the colonial master of the nation to the ruling Ivorian elite, which established the communal tribe tenure farming system mentioned previously. While farms in these tribes have no legal papers documenting what land or plantations they owned, ownership of plantations and of land plots were usually agreed upon collaboratively by farmers and landowners. The Ivorian government encouraged expansion and increased production, converting forests into more arable land. (Anti-Slavery International 2004) Unfortunately, the boone of wealth would only be temporary, as more change was soon to follow.

The death of traditional colonialism would soon mark the birth of neoliberalism. The end of colonial rule in West Africa would also mark the economic shift towards a globalized capitalist market. Empires of rule were replaced by chocolate company giants such as Mars, Cadbury, Nestle, and others (Food Empowerment Project 2022). Once tapped into the globalized market, these companies naturally chipped away the price of cocoa with competitive pricings and economic/political manipulation, making the raw cocoa product increasingly unsustainable for the nation. The depreciating market, combined with aging trees and decreasing land availability for production, would force the Ivorian government back into trade relations with similar dynamics of those during the colonial era. Expansion ceased in the 1980’s, but the consequences were still much apparent. The Ivory Coast was struggling to match production quotas to meet the needs of the country. All the while, chocolate companies hid their suppliers of cocoa in favor of a consumer-friendly image for a seemingly innocent product. As the chocolate companies we’re familiar with today achieved unprecedented growth, the source of their success continued to struggle economically and politically. The result was a weak supporting infrastructure, impoverished cocoa workers, a rising market for child-trafficking, children working in cocoa plantations rather than attending school, and an inherited invisibility (at least until the last 20 years or so) to the public sectors of consumers.

Similar to Rolph Trouiott’s ideas of a subjective past and historicity, the narrative of chocolate to consumers has historically left out the details of the laborers who made the product possible (Trouillot 1995). It is often understood that Africa is inherently poor and without a history. A common trend for many antiquated products, chocolate companies adopt the facade of a sanitized reputation, burying the truth behind flashy advertisement campaigns. Once again, the subaltern voices are silenced in favor of the protection of eurocentric interests.

In the perspective of Michelle Murphy, the people of Ivory Coast are forced to carry the colonial burden from 150 years ago (Murphy 2017). The cocoa farmers do not have a choice either, as cocoa production is essential for most smallholder families to make a living in the generational struggle of chocolate. Unlike the chemicals that accumulate in the physical body of the subaltern people in Murphy’s case study, the cocoa tree has accumulated in the economic structure of the Ivory Coast. And like the chemicals accumulated inside us, it is unlikely that the Ivory Coast will ever be able to abandon their cocoa, as it is their most stable link between them and the modern global market that supports their income flow Ivorian citizens have become reliant on.

Contemporary Ivorian Dynamics: Economic and Sociocultural

While sentiments on child labour understand that the practice is morally wrong in more developed countries like the US, the sociocultural dynamics of Ivorian Families are not the same as others. As mentioned previously, child laborers range from trafficked children, orphans, and children of cocoa workers. However, a large portion of child laborers fall into the familial category, especially for the small-holders farms that are family-owned. Child workers are often recruited by close or extended family members, a practice that is considered normal in the culture developed by decades of cocoa. A scholarly article from Milande Busquet et al. reveals that under the Sustainable Livliehood Approach of understanding the child labour in Ivory Coast plantations, a narrative is formed in which child labor becomes a commodity for the child, the community and the family. (Milande et. al 2021). With information collected from small-holder farmers in both Ghana and the Ivory Coast, the ethnographic researchers observed the communal tribal culture interconnected to the idea of land and property ownership. Tribal communities run plots of land through sharecropping-like systems, with each family responsible for a section of land. Children are included in this community and are viewed culturally as potential human and social capital. As cocoa is often the primary source of income for many families, children are often expected by the community to work under the adults to learn the craft of harvesting and processing the raw cocoa rather than going to school. The job is often seen as the child’s link to being a part of the community with work often being viewed as an internship, as well as a chore. The work prepares the children for their futures of harvesting cocoa, learning practical information while also helping the family in collections and processing.

It should be emphasized that many of the interviewed cocoa workers felt the children would be better learning a more traditionally academic education. However, due to poor infrastructure and unreliable education sources, parents often find themselves convinced that the children are better off staying with family and helping with work, a guaranteed certainty that will always be available for them. Under this perspective, child labor becomes a negative consequence of the resulting poverty from a struggling, unstable government resulting from the abuse of Western ideals. This approach to understanding resembles more closely the Global Value Chains perspective also discussed in the article(Milande et al. 2021). With both perspectives, we can understand the work of children in the family is an improvised form of cutting corners, supervising the children, teaching practical skills, and helping the family. While this may seem like a wholesome spin on child labor, one should remember that the only reason for the need to improvise these values is because large companies refuse to pay families livable wages that only adults need to perform to meet quotas. Additionally, while the larger portion of child laborers are from families, a portion of the children are still orphans or trafficked into the work, in which the values mentioned do not apply. They do not have the supervision of the family to look after them.

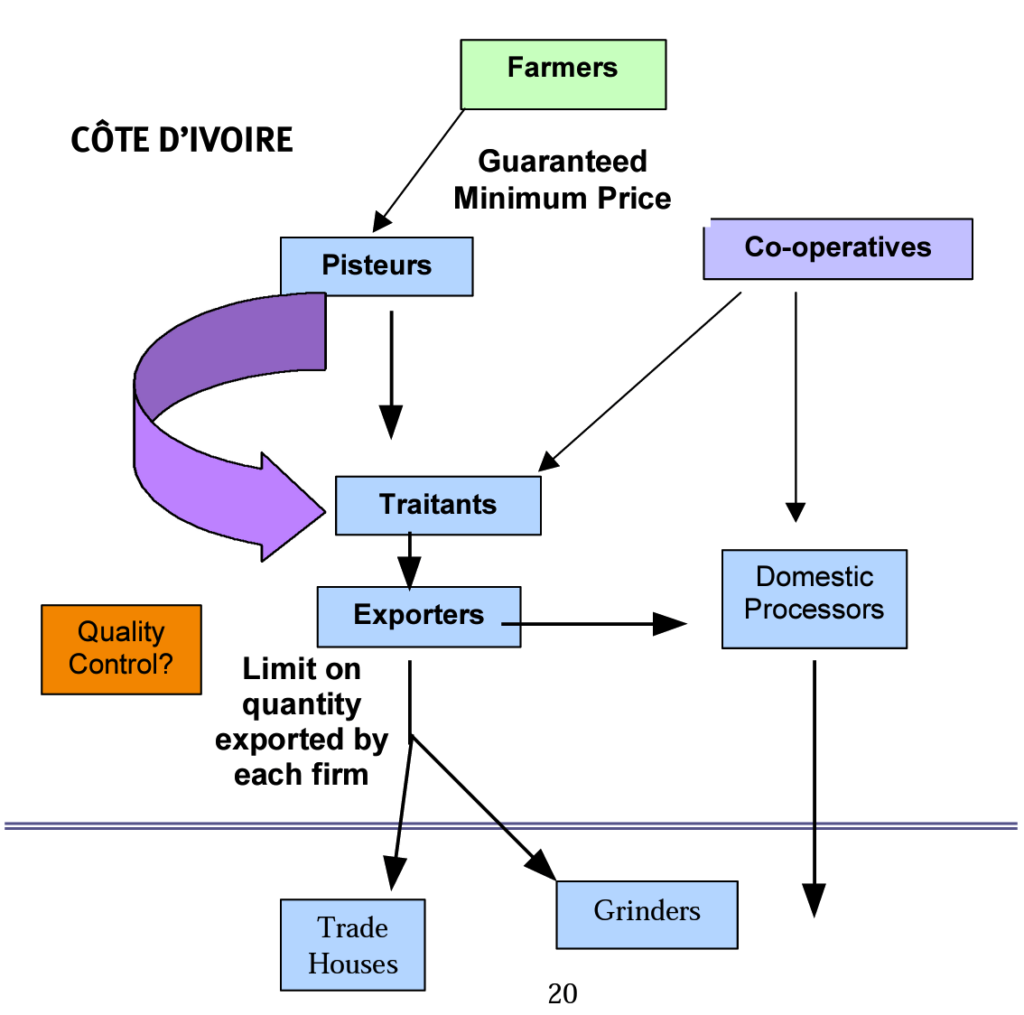

In addition to sociocultural dynamics in the Ivory Coast, the economic dynamics of trade are also helpful in understanding the systems of exploitation in play. Raw product goes through many middlemen, such as pisteurs, traitants, and cooperatives before being sold to exporters. With such a complex system of trade, it becomes clear how farmers can often become exploited in price. The blame of the complexity is partially due to the liberalization of the cocoa market in 1999 (Anti-Slavery International 2004).

The Modern Struggle: Issues that Remain, and the Modern Trade Dynamics

The year 2000 marked the release of Slavery: A Global Investigation, a documentary which explores modern forms of forced labor, including the Ivorian children (Woods and Blewett 2000). The documentary exposed the truth about the labor crisis in West Africa, revealing the desperateness of the workers and the children accessory to the operation. With the truth of chocolate exposed, the public became outraged with the associated companies. Boycotts and protests ensued, marking one of the first times in which the Western world was critiquing its own practices.

To quell the disapproval of child labour, in 2001, the chocolate industry collaborated together to announce the Harkin-Engel protocol, an anti-child labour initiative to eliminate all chocolate sourced from cocoa plantations using children workers by the year 2005. While the initiative was first very promising to the future of the chocolate industry, once fallen out of the news’ proverbial eye, companies became lax in their procedures. The deadline to end unethically sourced chocolate was missed, extended, and missed again. Eventually, the chocolate companies reformed their directive, aiming to reduce unethically sourced cocoa by only 70%. While the Harkin-Engel protocol failed to meet their initiatives time and time again, the chocolate paraded the minimal changes they did make with large press reports to maintain the facade that change is occurring. The project continues to be a major failure, with little to no enforcement of the rules by the industry and virtually zero legal action against those who disobeyed the ethical sourcing protocols (Siegel and Whoriskey 2019). As of 2023, the Harkin-Engel protocol still has yet to cut child labor by 70%.

The Ivory Coast along with Ghana, the two largest cocoa producers in West Africa currently, have recently taken another approach to increase financial gains in the country. Both countries implemented the Living Income Differential (LID) premium into their trade systems with manufacturing exporters (Collins 2022). The labor premiums charge an extra $400 for every ton exported from the countries. The $400 premium price was decided by both collaborating governments to request the bare minimum to allow for livable wages in the cocoa trade. While the premium laws provide promise for a better future, chocolate companies have already found loopholes around the requirements to pay more. By buying cocoa from a middle-man agency inside the countries rather than directly from the farmers and producers, the large companies are not required to pay LID premiums. Additionally, chocolate companies can displace LID premiums by dodging the origins differential, a premium based on provenance and inspected quality of the cocoa beans, qualities that can be very easily manipulated. The Ivory Coast and Ghana continue to attempt the enforcement of LID, with more West African countries accepting the premium to create a standard charge in Africa. Additionally, boycotts and manipulating the supply of cocoa in circulation have also been used as rebellious acts to persuade the stubborn chocolate companies to accept the premium as an industry standard.

Even as the systems of colonial rule recede into the past, the persistence of power dynamics and the abuse of the Ivory Coast continues into the present. Borrowing ideas from Ann Stoler about non-linearity of history, an analysis of the history of cocoa production highlights the uncanny similarities of labor sources and economic trends of modern day (Stoler 2016). The establishment of new laws, governments, and freedoms only become overshadowed with remaining colonial dynamics. The recursiveness of control, or lack of, remains, even with countries like the Ivory Coast and Ghana as a free nation.

Conclusions

The practice of child labor is best understood as an unfortunate byproduct of a nation perpetually performing the same service as their colonial ancestors. Restrained by the practice of neoliberalism and a global market, the people of Ivory Coast and West Africa experience poverty by forces outside their control, despite growing the base product for one of the world’s most popular sweets. However, there is a sociocultural aspect for child child laborers in the familial category which work due to their families believing it’s more beneficial for them and the community. This introduces a perspective where child labor in this category lies in a gray area, where neither outcome is completely favorable due to the instability of the Ivory Coast.

Regardless of any events during the creation of the West African cocoa empire and beyond, the only reason the plant was grown in Africa was because colonists saw the opportunity as a great way to maximize profits at the expense of the exploitation of Africa’s land and its people. The damage from the unforgiving plague of colonialism leaves the region with open wounds that postcolonial theory has only recently attempted to fix, albeit with heavy resistance with the companies implicated. Pushback for change continues today with big chocolate companies, as values are placed not in people, but money.

In my own opinion, the Ivory Coast will never be able to fully decolonize, as the countries’ infrastructure is essentially made on foundations of past colonizers’ intent. It’s plausible for the nation and other cocoa-associated West African nations to decolonize politics and development of the countries, but for a country like the Ivory Coast which primary sources of income are based off colonial systems, it’s hard to imagine a transition to a decolonial-based source of capital without endangering the people of the nation. It truly speaks volumes that even the country’s name is colonial in language and their main export isn’t even native to their country. In true decolonial theory, the Ivory Coast would become radically different from the raw cocoa producer observed today, if even possible at all. The only solution to such a substantial problem is to acknowledge the history, mend the damage, and most importantly, act against the companies feigning innocence. Once these actions are taken, maybe West Africa will decrease child labor.

Bibliography:

- Collins, Tim. 2022. “Ivory Coast battles chocolate companies to improve farmers’ lives.” Aljazeera, Dec. 8, 2022. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2022/12/22/ivory-coast-battles-chocolate-companies-to-improve-farmers-lives#:~:text=Ivory%20Coast%20produces%20around%2045,to%20the%20World%20Economic%20Forum.

- Busquet, Milande, Niels Bosma, Harry Hummels. 2021. “A multidimensional perspective on child labor in the value chain: The case of the cocoa value chain in West Africa”. World Development 146, Oct. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105601.

- Saripalli, Krishi. 2021. “Cadbury, Cocoa, and Colonialism in West Africa.” Brown Political Review. Jan. 4, 2021. https://brownpoliticalreview.org/2021/01/cadburycocoacolonialism/

- Ludlow, Helen. 2012. “Ghana, cocoa, colonialism and globalisation: introducing historiography.” Yesterday and Today 8, 01-21. Apr. 27, 2012. http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2223-03862012000200002&lng=en&tlng=en.

- 2004. “The Cocoa Industry in West Africa: A history of exploitation.” Anti-Slavery International. n.d., 2004. https://www.antislavery.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/1_cocoa_report_2004.pdf

- 2022. “Child Labor and Slavery in the Chocolate Inudustry.” Food Empowerment Project. Jan. 2022. https://foodispower.org/human-labor-slavery/slavery-chocolate/

- Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. 1995. ”The Power in the Story.” Silencing the Past : Power and the Production of History. 1-30. Boston, Mass. :Beacon Press

- Murphy, Michelle. 2017. “Alterlife and Decolonial Chemical Relations.” Cultural Anthropology 32 (4). 494-503. http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5173-1717

- Siegel, Rachel, and Peter Whoriskey. 2019. “Hershey, Nestle and Mars Won’t Promise Their Chocolate Is Free of Child Labor.” The Washington Post. WP Company, June 5, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2019/business/hershey-nestle-mars-chocolate-child-labor-west-africa/.

- Stoler, Ann. 2016. “Critical Incisions.” Duress: Imperial Durabilities in our Time. 3-36. Durham, NC: Duke Press.

- Woods, Brian and Kate Blewett. 2000. Slavery: A Global Investigation.