by Diego M. Almaraz

When we think of the indigenous peoples of Mexico, we are often tempted to think of the great civilizations of old such as the Aztec Empire or the Classical Maya Civilization. One perhaps more knowledgeable in contemporary affairs might be familiar with the indigenous groups which still exist today in significant number such as the Nahuas, Yucatec Maya, Zapotec, or Otomi. Less well known, however, is the group known as the Lacandón. A relatively obscure group of around 1000 individuals, these people live in their namesake jungle, La Selva Lacandona, in the southernmost state of Mexico, Chiapas. This group’s long, obscure, and somewhat misappropriated culture has been the subject of great interest from both western academics and the Mexican government. In this paper, I will outline a brief history of these people and describe how many of the contemporary problems they face today are the result of poor government policy and false lenses of historical interpretation.

It is important to note that the Lacandón are divided into two distinct but related groups, northern and southern. This genealogy, of sorts, will primarily focus on the northern though much of the history and many of the problems that afflict the northern group are applicable to the southern group as well.

Who are the Lacandón Maya?

The Lacandón Maya are a group of Maya people who live in the Chipas, Mexico. Residing on land in the jungle, they are nowadays concentrated in 3 main settlements, the villages of Najá, Mensäbäk, and Lacanjá (Palka 2008, 110). They speak a variant of the Maya language most closely related to Yucatec (McGee 2002, 4). The traditional image and lifestyle of a Lacandón was characterized by both men and women wearing knee-length cotton tunics, with women sporting skirts in addition. Men wore their hair long and uncut (McGee 2002, 30). Their traditional beliefs involve incense burning, divination, and the drinking of Balché (Palka 2008, 110).

However, these days substantial change brought from the outside world has radically altered this character. Nowadays, the Lacandones can be found wearing typical western clothing, watching telenovelas, and speaking Spanish (McGee 2002, 30). Their traditional belief system has, for the most part, fizzled out and the language remains critically endangered (McGee 2002, 44). Where once they lived as primarily slash-and-burn horticulturalists who raised maize, beans, root crops, bananas, and more in fields called milpas, nowadays they have adapted to a tourist economy (Palka 2008, 110). New economic pressures have substantially altered the means by which they make a living (McGee 2002, 26).

In terms of defining themselves, the Lacandones categorize human beings into four groups: In their native tongue they call themselves Hach Winik, meaning real people and they call their language Hach T’an, meaning true language; Other indigenous peoples are called Kah; foreigner men are called tsur and foreign women are called xunaan (McGee 2002, 30). Anthropolgist, R. Jon McGee, has found that “the single diagnostic characteristic of Lacandoness is that one’s father is Lacandón” (2002, 31).

Regardless of how you see them, the Lacandón are a people with a rich history and they, as a people, have evolved consistently throughout that history. Living in isolated, dispersed communities for much of their history, they have had frequent contact with the outside world on their own terms. Today however, the modernity of “civilization” has crept into their world and radically altered the ways in which they interact with the outside world. Pressured by outside migration and external economic forces, their numbers have dwindled and their lives remain forever changed (Palka 2008, 110).

History

In the years following the Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire, numerous conquistadors were sent out to consolidate Spanish rule in the regions surrounding central Mexico. In the lowlands, situated near the modern-day border of Mexico and Guatemala, the Spanish encountered the Chol-Lacandón, another Maya people. During the 16th century, they were subject to numerous Spanish raids and occupation. The coming of the conquistadors saw much of their population die in battle, be enslaved, or die from diseases brought by the Spanish such as smallpox. In the following century, a number of reducciones campaigns would see the forcible relocation of virtually the entire Chol-Lacandón population such that by the start of the 18th century, their population in the Chiapas lowlands were entirely wiped out or relocated elsewhere to be used as labor and converted under the eye the Spanish colonial system (McGee 2002, 4-6). It was in the wake of this rapid and massive depopulation of the jungle that groups of Yucatec-speaking Maya moved in. Moving westward from Petén in modern-day Guatemala and into Chiapas, they slowly trickled into the region becoming the dominant population (McGee 2022, 7). These people are the people who would become the ancestors of today’s Lacandones. It was the jungles of southern Mexico that had often served as a place of refuge for indigenous peoples looking to escape Spanish rule, and it was here too that the Lacandones established a relatively high level of isolation from the outside world. It is important to note here that the name Lacandón was itself a vague term used by Spanish colonial authorities to describe a variety of unconquered, non-Christian peoples in southern Mexico (McGee 2002, 4).

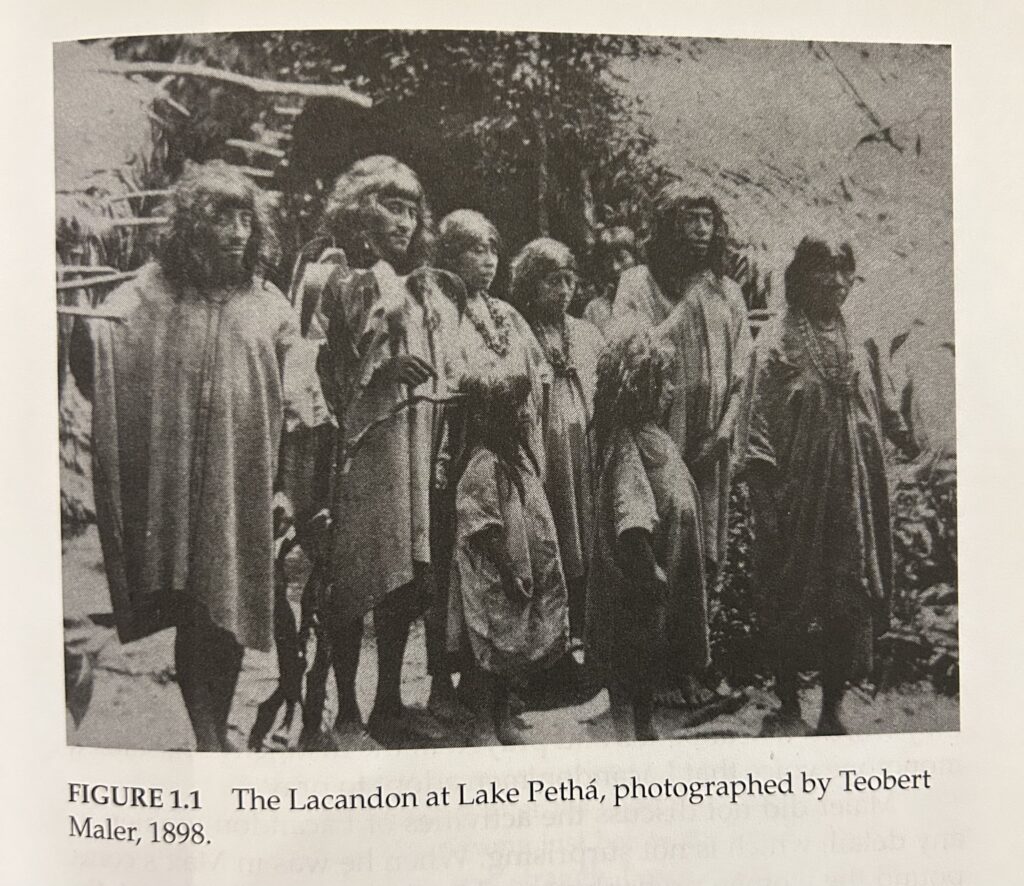

Despite their relative isolation, the Lacandones did have contact with the outside world. It was through these moments of outside contact that the Lacandones would trade goods such as bows, crops, and other goods for metal tools, cloth, salt, and other manufactured items (Palka 2008, 111). The earliest records of the Lacandones come from reports of Lacandón men trading in the town of Palenque and even reports of marriage between them and local women. In 1793, Father Calderón, a missionary, established the mission of San José de Gracia Real (McGee 2002, 8-9). The site was chosen by the Lacandones because of its advantageous location. It was here that the classical, stereotypical image of a Lacandón person emerged. Early accounts describe the long hair styles and the rough cotton tunics. Calderón, also described their communities as being dispersed settlements situated in or around milpas, a type of sustainable field used for growing crops (McGee 2002, 9). Their dwellings were unwalled, thatched huts and the people slept in hammocks. It is also here that the Lacadones’ system of strategic trade and barter with the outside world was established. Despite the mission’s best efforts, few Lacandones converted to Christianity, and those that did usually still clung to their old religious tradition involving burning incense, making offerings to the gods, and the drinking of balché (McGee 2002, 8). In fact, trade was probably the primary motivation of the Lacandón congregation to the mission. By 1807, the site had been completely abandoned (McGee 2002, 9). While intermittent contact persisted, it wasn’t until the late 19th and early 20th centuries that we see a number of pivotal contacts by western explorers. Of these, notable was German explorer Teobert Maler and Harvard anthropologist Alfred Tozzer. On September 3rd 1898, Teobert Maler, looking for the lost lake of Petha, encountered canoes and an abandoned Lacandón village (McGee 2002, 15). After exploring the area for some time further, he and his party encountered a Lacandón man, seemingly uneasy with their presence, as they tried to trace a series of rock paintings (McGee 2002, 16). It was this encounter that brought Maler into closer contact with the Lacandones as he managed to convince them to shelter his exploration party for some time. It was here that some of the first photographs of the Lacandones were taken.

Years later, in 1903 and 1904, Alfred Tozzer, a Harvard anthropologist, set out to study ancient Maya ruins in Chiapas. During his time there, he would make a number of descriptions of Lacadón life, notably detailing the Lacandones’ trade with monterías, or camp stores that served local lumber companies in the region (McGee 2002, 19-20). He also focused extensively on their religious practices, involving gods’ houses where, again, incense was burned and offerings were made to the gods (McGee 2002, 20).

The Problem of History

In briefly analyzing the history of the Lacandones, we discover the first problem afflicting them, representation. One of the chief problems afflicting academic study of the Lacadón people in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was a historical myth. That myth viewed the Lacandones as the direct descendants of the classical Maya (McGee 2002, 1). As such, they were thought to be an untouched and pure representation of what the old Maya civilization looked like (Gollnick 2008, 71-76). Maler, for example, tried to search for ancient Maya glyphs among the Lacandones but found nothing (McGee 2002, 17). Tozzer, for his part, attempted to claim that the religious practices of the Lacandones were a continuation of ancient Maya religious practices; however, the Lacandones were dumbfounded by anything that Tozzer tried to show them from the Maya codices (McGee 2002, 19). This narrative would remain prominent among scholars well into the 20th century despite all the evidence which suggested much to the contrary. The fact that they have a history of frequent trade with the outside world since at least the 18th century only further reinforces the idea that they are not simply an untouched and entirely isolated community (Gollnick 2008, 72). The simple reality is, historically they have as much connection with the classical Maya as any other Maya people, be it culturally or religiously.

This idea of the untouched native also peeks its head into the contemporary era as well. Modern tourist agencies in Chiapas will often market the trips through Lacandón territory as a chance to glimpse into the ancient Maya civilization, ignoring the fact that many Lacandón today dress in ostensibly Mexican clothing and possess modern technology like TVs (McGee 2002, 30) The Mexican government too is not shy about using the stereotypical image of a Lacandon to hold up as a model indigenous group that needs protecting (Gollnick 2008, 72). While not seemingly bad, viewing protection of indigenous groups through incorrect historical lenses can lead to paternalistic attempts at protection. Brian Gollnick, in writing about the Lacandón, describes this phenomenon as the “allegory of redemption” as a dominant society uses historical revisionism to imagine ways to right historical wrongs committed against other indigenous groups (Gollnick 2008, 72). This can lead to a number of problems. Because the group has come to be romanticized, attempts at protection are often built on the terms of the dominant colonial society rather than based on the input of the locals. It can also lead to an overlooking of other indigenous groups as the allegory of redemption provides justification for Mexico’s own contradictory policies toward the protection of indigenous groups. Rather than focus on those groups who exist now, the Mexican state focuses on protecting a romanticized ideal of the indigenous group feeling good in the thought that it has “protected” the last remnants of “untouched” pre-colonial society.

This problem, of viewing the Lacandones as pure and untouched, taps into another pressing problem, the denial of coevalness or the denial to see another group as existing in the same time as oneself. Sitting on the periphery of Mexican society, the Lacandones of Chiapas acted as a gateway for the Mexican government and many scholars of the 20th century to a long-lost world. In this way, the Lacandones are turned into a sort of model native to be learned from and who will provide absolution for the colonial crimes of the past. Viewing “isolated” groups as pure, untouched, and existing in a different time isn’t a new idea either. Such ideas actually stem from older indigenous stereotypes such as the Quechua concept of auca, a word used to describe Amazonian groups with little outside contact (Gollnick 2008, 76). The reemployment of these old stereotypes by colonial forces is something Anthropologist Michael Taussig termed the “colonial mirror of production” (Gollnick 2008, 76). By redeploying older stereotypes from indigenous groups, colonizing forces and, indeed, much scholarship in the 20th century, justify the violence of the colonial past by viewing colonial violence as barbaric but working in service to taming another barbarity, indigenous “barbarity”. Thus, the “civilizing” missions of yore, or the recognition and protection project of today, act as a means by which to grant the colonizer absolution for the violence of colonialism. Indeed, during the late 1940’s, scholars collaborating with the University of Chicago went as far to make the Lacandón society point zero for measuring the “civilization” and cultural change of other indigenous groups in Mexico (Gollnick 2008, 77).

The totality of all this, the romanticization and the false lens of history serve as a clear example of what Edward Said dubbed “Orientalism”. In this sense, Said tells us that the orient is viewed as “a place of romance, exotic beings, haunting memories and landscapes, remarkable experiences (Said 1978, 1). The Lacandón and their history are treated as an exotic other, something to be spoken for just like the Egyptian woman, represented in the works of Flaubert, as described by Said (Said 1978, 6). What we see then is that the very history of the Lacandones is Orientalized so as to be made subject to the needs of the colonizer. This is possible precisely because they are viewed as existing in a different era, outside of our own, even if history and the modern-day suggest otherwise. For the Mexican government, this Orientalization serves as a tool of absolution and as means to control the narrative on their indigenous policy.

Contemporary Problems

Of course, faulty views of history and the denial coevality are not the only problems the Lacandón face. There are a number of material, contemporary problems which afflict the Lancondes in more recent times. During the 1930’s and 1940’s a series of land reforms initiated by the government of Mexico made the rainforests of Chiapas national territory and opened it up to colonization (McGee 1990, 4). Since the Second World War, Mexican industries have also increased the rate of exploitation of their traditional lands (McGee 1990, 4). This has brought vast swaths of settlers, mostly other groups of Mayas such as Tzeltal and the Chol, descendants of the Maya people who had been displaced centuries earlier by the Spanish (McGee 1990, 4). By 1954, a new community was founded by people of Tzeltal and Chol descent called Lacandón (McGee 2002, 24). Further land reform in the 1970’s further eroded the land rights of the Lacandón bringing in settlers from as far away as Sonora (McGee 2002, 24). These new settlers put increasing pressure on Lacandón communities forcing them to abandon their dispersed settlements for a number of consolidated settlements such as that of Mensäbäk (McGee 1990, 5). Along with the new settlers came increased development as these primarily agrarian settlers sought to cultivate their new land given to them by the Mexican government (McGee 1990, 4). The 1970’s also witnessed the increased presence of lumber companies and the construction of many new roads further contributing to the erosion of the Lacandón land rights and the deforestation of La Selva Lacandona. However, in an odd contradiction of policy, the Mexican government established Zona Lacandona, a reserve intended to help protect against deforestation (McGee 1990, 5). Moreover, much of the land rights were given to the Lacandones while the Mexican government kicked out settlers who had come to the region due to land reform policies (McGee 2002, 5). The end result is substantial animosity between native groups aimed at the Lacandones who they perceive as receiving special treatment, especially given their small population size (McGee 2002, 5). What’s more, the Mexican government has, since the 1980’s, done a relatively poor job at enforcing the land rights of the Lacandones leading to frequent land disputes and infringement of their territory (McGee 2002, 5). Seeking simple protection of their land and lifestyle, the Mexican government has, in effect, established a highly contentious set of recognitions that have led only to increased animosity aimed at the Lacandones and done more damage to the actual protection of their lands and livelihood.

What we can take away from these land relations established by the Mexican government is that the problem extends from what Glen Coulthard dubbed “the politics of recognition” (Coulthard 2014). What we see is that in attempting to correct the wrongs of the colonial past, the Mexican government has established various laws and reforms; however, these recognitions have only created further problems. In summarizing the work of Frantz Fanon, Coulthard tells us that “when delegated exchanges of recognition occur in real world contexts of domination the terms of accommodation usually end up being determined by and in the interests of the hegemonic partner in the relationship” (2014, 12). And this is precisely what we see in the case study of the Lacandones. Relations are established, seemingly to make right for the wrongs of the past, yet it is done so on terms favorable to the Mexican government. The Lacandones are used as a “model tribe” while their land rights go relatively unenforced against outside incursion. By creating animosity among tribal groups directed at the Lacandones, the Mexican government makes itself both the instigator of inter-indigenous violence and the protector and mediator. In this sense, they make the various indigenous groups dependent on official state solutions, hindering the possibility for reconciliation. It also acts as a means to direct attention away from the government’s own shortcomings in indigenous policy. Furthermore, we can also see how the Mexican government has been able to utilize its indigenous policy for its own ends. The substantial land reform policies implemented by the Mexican government encouraged massive migration, of people and companies, into the traditional homelands of the Lacandones; since then, the Mexican government has also invested substantial amounts of many toward development projects in the region (McGee 2002, 75). This confirms what Coulthard says when he talks about settler-colonialism as being a form of domination meant to dispossess natives of their land (2014, 5). By utilizing their indigenous policy, the Mexican government was able to engage in a project of development of these “undeveloped” lands showing the inextricable relationship between capitalist development and the colonial project and further showing how, through the politics of recognition, Mexico used indigenous systems of recognition to support their own hegemonic ends.

Along with the issue of erosion of land rights and problematic relationships forced onto them by short-sighted government decisions, the Lacandones have also experienced substantial change to their lifestyle from outside pressure. The influx of new settlers along with the building of new roads has led to an influx of new things into Lacandón society (McGee 2002, 27). Where once the Lacandones met with the outside world on their terms, the outside world has come to them. Following the weakening of the oil market, Mexico’s highly oil centric export economy suffered greatly in the 1980s (McGee 2002, 26). The result was a significantly weakened Peso that proved highly lucrative to western tourists. While the Lacandones remained relatively unaffected by the economic downturn of Mexico, the sudden influx of tourists proved a lucrative economic opportunity. Adapting to the changing times, many Lacandón men have set to producing quintessentially Lacandón goods and trinkets to sell to foreign tourists interested in attaining an authentic piece of Maya civilization (McGee 2002, 48). The 1990’s also witnessed the arrival of electricity, satellite and dish television, and telephone service (McGee 2002, 27). The net result has been the transition of Lacandón society from primarily subsistence living to the full-time sale of crafts. Furthermore, the influx of outside culture has essentially completely eroded the practice of Lacandones’ traditional religion (McGee 2002, 27). They haven’t converted to an outside religion, rather most young Lacandón have, since the 1990’s, had little interest in the traditions of their predecessors except insofar as it sells for tourists (McGee 2002, 48). When the tourists are gone, few participate in the traditional religious practices.

Conclusion

The Lacandon Maya are an indigenous group in southern Mexico who live in the state of Chiapas. They have a long, obscure history, and today they suffer a number of problems ranging from internal colonialism, eroded land rights, contentious relations, and the commodification of their culture. While modern scholarship has rejected the outdated romanticization of Lacandón culture as pure and untouched, modern touring companies and tourists themselves often don’t know this (or choose to ignore it). It can be hoped that in the future, the Mexican government will grant more agency to these peoples and work to solve the contentious land disputes that afflict the Lacandones today. Regardless, it is important to recognize that these people are people in their own right, people that seek to make a living and protect their families. While the erosion of traditional culture may be regrettable, it is still their culture and it is their choice of which direction they want to take it, be it in terms of preservation or a move toward something else. All we can do is work to facilitate it by providing them as much agency as possible lest we make the mistakes of scholars and government officials of the past.

Bibliography

Coulthard, Glen Sean, and Taiaiake Alfred. “Red Skin, White Masks,” 2014. https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816679645.001.0001.

Gollnick, Brian. Reinventing the lacandón: Subaltern Representations in the Rain Forest of Chiapas. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2008.

McGee, R. Jon. Watching Lacandon Maya Lives. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 2002.

McGee, R. Jon. Life, Ritual, and Religion among the Lacandon Maya. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company, 1990.

Palka, Joel W. “Lacandones.” In Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, 2nd ed., edited by Jay Kinsbruner and Erick D. Langer, 110-111. Vol. 4. Detroit, MI: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2008. Gale eBooks (accessed April 27, 2023). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX3078903078/GVRL?u=unc_main&sid=summon&xid=50bcfc49.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York, 1978.