By Kayris Baggett

Colonial ideals are inextricably intertwined with the process of knowledge production in biomedicine, perhaps especially with regard to the infectious disease subspecialty. Whether through the direct treatment of colonized people as bodies for experimentation or the integration of colonial doctrine within medical teachings, the relationship between colonialism and Western infectious disease is undeniable. The discipline’s former name—tropical medicine—is itself a glaring example of the imperialistic undertones that ran (and still run) rampant in the making and practice of this field. Taking a critical anthropological lens to the histories of knowledge and knowledge production associated with tropical medicine, with a special focus on dengue fever, allows one to grasp colonial realities as they exist today within infectious disease and biomedicine at large.

In order to properly analyze this case study and its implications, one must first understand the etymology of infectious disease as a medical discipline. In the current age, infectious disease seeks to diagnose and treat patients from within the clinical setting. Epidemiology is the study of broader patterns of disease distribution and control, informing practice and policy in the adjacent fields of public and global health. It was not long ago, however, that these two branches were synthesized under the umbrella of tropical medicine, with the common goal of characterizing and documenting maladies hitherto unseen by Europeans as they colonized equatorial regions. Indeed, it can be said with certainty that tropical medicine was an inherently colonial project. This new knowledge system was designed to inform and protect the colonizer, not the colonized: Western doctors needed to understand how to treat soldiers and colonists as part of preserving colonial power structures (Hirsch and Martin 2022). Thus, a positive feedback loop between tropical medicine and colonialism developed from the specialty’s inception in the late 19th century. As the search for new colonial markets in Asia “transformed the basic premises of modern medicine,” the doctor came to be regarded as the “most effective and penetrating agent of peaceful colonization” (Chakrabarty 2014: 2; Todd 1902: 155). Early bacteriology and parasitology played supporting roles in the civilizing mission of the colonist-savior, while European tropical medical schools made “creating European colonizers” part of the standard curriculum (Neill 2012: 44). Tropical medicine became a cog in the colonial machine, using conflations of modernity and Western-ness to justify the continued appropriation of resources, land, and lives.

Case Study: Dengue Fever

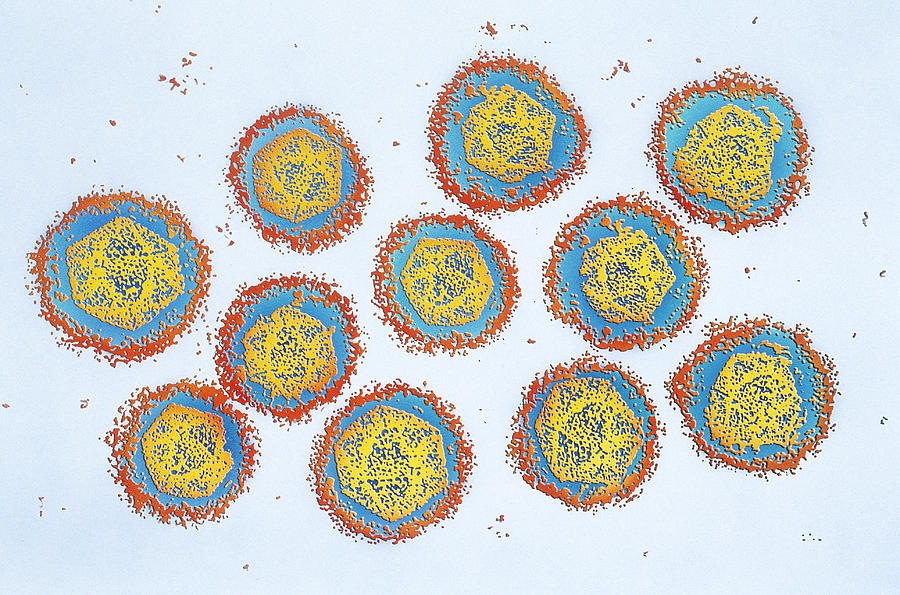

While the aforementioned conflations thread through many colonial histories—some of which are still being written—dengue in Southeast Asia serves as an excellent example. Almost entirely colonized by European powers by the late 19th century, the region provided a plethora of endemic pathogens to fuel the emerging specialty of tropical medicine (Hafner et al. 2005). Dengue virus is but one of these agents of illness. Accounts of clinically compatible diseases dating back as far as 992 AD indicate that it has thrived in this domain for a very long time (Gubler 2006). Believed to have originated in sylvatic cycles in Asia two to four thousand years ago, the dengue microbe made the jump to humans via mosquito vectors within the last millennium, and is now known to have four main serotypes (Health Desk 2022).

Although dengue virus flourished in pre-colonial Southeast Asia, it positively proliferated with the help of imperial endeavors and globalization in general. The first confirmed dengue fever pandemic was documented in 1779, sweeping across Asia, North America, and Africa, presumably aided by trade routes and interdependent commodity chains (Health Desk 2022; McMichael 2011: 9). Port cities developed for the export of extracted goods were prime breeding grounds for mosquitoes, and travellers brought them and their viral cargo to new areas. This included transporting different serotypes to new locations, opening populations to re-infection and, as a result, to the much deadlier manifestation as dengue hemorrhagic fever.

Regardless of its prevalence, dengue remained largely outside of public (read: European) consciousness. With the slightest bit of research into why this may be, one is forced to reckon with the colonial design of disease hierarchies and their impact on clinical research and treatment development. Ailments that captured public attention and much-needed private funding, such as leprosy or cholera, were usually associated with high mortality or morbidity rates, highly visible signs of disease, or “specific cultural resonances” that inspired fear, sympathy, activism, or a combination of the three (Meerwijk 2018: 2). Dengue fever did not carry these connotations. It was generally non-lethal, had a short course of illness, failed to cause major epidemics in northern imperial centers, and was dwarfed in importance by its flashier and more worrisome cousin, yellow fever. And so, it became an out-of-sight, out-of-mind disease for most colonizers… until the United States took over the Philippines following the Spanish-American War. After their arrival in 1898, troops were “encumbered” by non-deadly dengue; only when it became “a source of considerable economic loss to the Army” and an overall nuisance did it become worthy of study by American tropical disease specialists (Meerwijk 2018: 5). Even then, no notable strides were made, and the quantities of research related to local post-war struggles—illness-related or otherwise—and to the impact of tropical disease on U.S. soldiers are somewhat disappointingly similar. As will be discussed later, this mindset persists to this day, and dengue continues to inhabit the fringe of medical consideration.

The next major set of dengue-related concerns arose in the wake of World War II. The destruction of towns and cities in Asian theaters of war would have left many without access to clean running water, creating an ideal environment for mosquito-borne illnesses. The other side of the coin was not any better. As Southeast Asian nations gained independence between 1945 and 1957 and reconstruction efforts got underway, massive urbanization was frequently quick to follow (Metropolitan Museum of Art 2004). Subsequently, dengue and many other viruses became hyperendemic, and these populations were the first to fall victim to the aforementioned fatal dengue hemorrhagic fever (Gubler 2006). Finally, the founding of the World Health Organization in 1948, intended to serve as a unified authority on global health under the umbrella of the United Nations, filled the vacuum of healthcare-related resources and support for newly independent nations. The potential for International-Monetary-Fund-like dependence concerns aside, one cannot ignore the fact that the WHO was white-dominated in its infancy, if not still. The authors of the book on international public health most likely shared a very similar mindset: that of a white, Western-educated, financially-well-to-do, cisgender, heterosexual male. This is an enduring truth for many dominant occidental knowledge-producing fields, including biomedicine.

These ideological hegemonic structures persisted in tropical medicine throughout (and after) its integration into infectious disease, epidemiology, and public and global health as we know them today. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever remain unsolved problems, and a case in point. There are no effective antiviral drugs. While there are two approved vaccines, only one (Dengvaxia) is designed for all serotypes, and it confers only partial non-lifetime immunity in 50% of recipients, requires three doses over the course of a year (which can present major accessibility issues), and its recipient population is limited to children aged nine to 16 with a laboratory-confirmed history of dengue living in high-risk regions (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2023). The only large-scale mitigation efforts are mediated by the World Mosquito Program (WMP), which releases modified mosquitoes to reduce the transmission capability of dengue, chikungunya, yellow fever, and Zika vectors without compromising ecosystems (2012). While the WMP’s method has proven to be sustainable and effective in protecting humans from these pathogens, it takes time for the reduced-transmission trait to accumulate in a sufficient proportion of the mosquito population, and faster solutions with more guaranteed results would be ideal. Nevertheless, dengue fever is but one of twenty neglected tropical diseases, or NTDs, affecting an estimated one billion people across the globe (World Health Organization 2023). Upon closer inspection, it becomes evident that disparities in disease distribution play a significant role in maintaining the patterns of uneven development which underpin global inequality (Escobar 1994). The socioeconomic burdens associated with NTDs support neo-colonial power dynamics by reinforcing the cycles of poverty in which so many former colonies find themselves after gaining independence. The often already overloaded and under-equipped state of new nations’ healthcare systems and general infrastructure is exacerbated to a devastating degree. It is indubitable that many of the factors which caused dengue and similar ailments to fall through the cracks of scientific research in the 19th and 20th centuries are still applicable to NTDs today. One could wonder if, with global warming broadening the latitudinal range deemed habitable by certain disease-carrying mosquito species, these forsaken maladies will gain more attention as they affect Western powers to greater extents, as with dengue following the American occupation of the Philippines. Ongoing struggles to transcend colonial constructions of recognition and difference could become indisputably conspicuous if NTD-related research expands in correlation with Western interests. In being explicitly designated as ‘other’ and ‘lesser’ relative to illnesses that occupy more prominent positions in public and scientific consciousness, NTDs can be viewed as colonial legacies being acted out on the global stage before our very eyes. Infectious disease and public health understandings, hierarchies, and endeavors continue to be embroiled in the politics of recognition.

Future Directions

With all that being said, the concept of decolonizing infectious disease and biomedicine at large is a daunting one. The knowledge used in medical education and practice (and those of many other fields) today relies on understandings gained via colonial means and conveyed by conventionally Western authors. Knowledge represents a fundamental form of power: the thought system established as ‘objective’ and ‘pure,’ key tenets in Western biomedicine, was and is used as an instrument of colonial dominance. In this vein, history legitimizes and perpetuates colonial systems of thought and power because it has the potential to, and often does, marginalize or altogether remove alternative voices. This realization raises concerns related not only to the teaching of historical knowledge, but also to the production of it, as these unilateral narratives frequently serve as the bases for further history-writing. What are the ramifications of standards or histories established using knowledge from a homogenous set of perspectives? How do we grapple with the voices that were and are overwritten or erased? How do we parse out these concerns and their heavy implications for the teaching, learning, and application of medicine as we know it? Michel-Rolph Trouillot offers some reassurance that these questions are potentially answerable. Firstly, by remaining cognizant of the politics contributing to which stories are told and by whom, one can begin to pick away at these concerns (Trouillot 1995). Secondly, one cannot ignore the ways in which histories are made through their telling in the pursuit of a complete ‘truth.’ Lastly, maintaining an awareness of silences, blank spaces where subaltern perspectives could and should exist, is imperative. These principles are all applicable to decolonizing the medico-historical record. While there are, of course, complicating factors—for example, not every actor is aware of their agency in the creation of knowledge, its documentation, or its teaching—making these part of a standard approach to learning may be sufficient to begin the process of unraveling everyday colonialities in the classroom. Jennifer Johnson supplies further impetus (2016):

[One must find] ways to dismantle binary pairings, most notably, metropole/colony, Western biomedicine/“traditional” medicine and colonial/post-colonial. These points of intersection… point toward a continuum, rather than a rupture, of time and space, thus pushing historians to re-evaluate medical authority, scientific knowledge production and local agency in the twentieth- and twenty-first centuries.

Her words invoke the work of Arturo Escobar in their call to construct different ontological vantage points that diminish the dominance of black-and-white dichotomies (2018). Euro-centric vertical hierarchies have fundamentally infiltrated our methods of structuring knowledge, down to the very ways we perceive the world. It is easy to see these stark divisions in action in Western biomedicine, with its implicit presumption of the Cartesian duality among others such as normal/abnormal, right/wrong, central (biomedicine itself)/peripheral (every other healing system). When one considers these profoundly ingrained divisions in conjunction with those to which decolonial theory is sometimes susceptible, the potential benefit of pluralizing thoughts and histories as part of the postcolonial project is undeniable. Approaching knowing and learning from a position of horizontal relationality would more authentically recognize and reflect the diversities of the lived human experience. With ideas from Trouillot, Johnson, and Escobar, one can begin to re-balance the unequal power dynamics behind dominances and silences in knowledge on an everyday basis—and it is these kinds of small-scale consistent efforts that create widespread, deep-rooted change. Although it may not be easy or simple to implement these notions, they impart some level of hope unto aspiring un-doers of colonial influence.

Encountering colonial influences within facets of Western society is less akin to finding a needle in a haystack and more to bumping into a pachyderm in a room full of elephants. The fundamentally colonial nature of tropical medicine and related younger fields continues to manifest in the ways we understand and approach disease, including dengue fever. Despite its relatively lengthy history, dengue has yet to receive the level of public attention or scientific research necessary to generate effective treatments and vaccines. This illness, along with the twenty other neglected tropical diseases, is something of an orphan in the worlds of biomedical and public health, in large part due to inherited colonial designs and hierarchies. It is what we do with our awareness of these inheritances that will define our success as contributors to the postcolonial project. Classic defenders of critical theory call us to rebel against the often insidiously ubiquitous colonial regimes of truth that run deep within global society today. We must approach dominant histories with open eyes in order to understand what lies beyond such limited narratives, and actively seek out subaltern voices. We must deconstruct old systems of recognition and create new ones that make space for multiple stories and knowledges. We must release reductionist dichotomies that keep us from coexisting within that kind of plural space. In the style of Escobar, our world is ours to make and unmake within the pluriverse… not at the expense of others, but in concert as mutually flawed beings just trying to comprehend a little more about life and living than we did before. Ours is a complicated and sometimes dauntingly damaged society, but it is with hope and pragmatic optimism that I leave you with these words from Ari Satok:

Fear cannot be quarantined

But neither can love,

Kindness too can spread,

Catastrophe can hold in it the seeds of compassion If we choose to let them grow.

Works Cited

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “The Dengue Vaccine.” Last modified April 3, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/vaccine/parents/eligibility/faq.html.

Chakrabarty, Pratik. Medicine and Empire: 1600-1960. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

Escobar, Arturo. Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994.

Escobar, Arturo. Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018.

Gubler, Duane J. “Dengue/Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever: History and Current Status.” Novartis Foundation Symposium 277, no. 1 (2006): 3-16. https://doi.org/10.1002/0470058005.ch2.

Hafner, James A., et al. “Thailand.” Encyclopaedia Britannica website. Accessed April 22, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/place/Thailand/The-postwar-crisis-and-the- return-of-Phibunsongkhram.

Health Desk. “What is dengue and where did it originate from?” Last modified July 21, 2022. https://health-desk.org/articles/what-is-dengue-and-where-did-it-originate-from.

Hirsch, Lioba A., and Rebecca Martin. “LSHTM and Colonialism: A Report on the Colonial History of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (1899– c.1960).” Project report, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 2022. https://doi.org/10.17037/PUBS.04666958.

Johnson, Jennifer. “Review: New Directions in the History of Medicine in European, Colonial and Transimperial Contexts.” Contemporary European History 25, no. 2 (May 2016): 387-99. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26294107.

McMichael, Philip. Development and Social Change: A Global Perspective. Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press, 2011.

Meerwijk, Maurits Bastiaan. “Dengue Fever, the Rockefeller Foundation, and Southeast Asia.” PhD diss., University of Hong Kong, 2018.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Southeast Asia, 1900 A.D. – present.” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, October 2004. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/?period=11®ion=sse.

Neill, Deborah J. Networks in Tropical Medicine: Internationalism, Colonialism, and the Rise of a Medical Specialty, 1890-1930. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2012.

Satok, Ari. “Untitled Poem.” Unknown date, accessed March 23 2020.

Todd, John to Rosanna Todd, letter of December 3, 1902, in Letters, p. 155.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press, 1995.

World Health Organization. “Neglected Tropical Diseases.” Last modified January 16, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/neglected-tropical-diseases#:~:text=Neglected%20tropical%20diseases%20(NTDs)%20are,who%20live%20in%20impoverished%20communities.

World Mosquito Project. “Our Wolbachia Method.” Accessed April 25, 2023. https://www.worldmosquitoprogram.org/en/work/wolbachia-method.