by Regina Lowe

Abstract

By following the life of chemical products from an area of concentrated petrochemical production in Louisiana (LA), I argue that chemicals are material artifacts that collapse temporality by building on the contingencies of the past and extending into the lives of individuals in the present and future. Drawing on post-humanist ideas and the writing of Michelle Murphy (2017) and Anne Laura Stoler, (2016) I situate this work as continuing to confound the boundaries between the human and non-human as well as the boundaries between past and present. The historic plantations in Ascension Parish, LA are archaeological examples of colonial contingencies making way for the petrochemical plants of Geismar, LA. By examining records from the plantations of Ashland-Belle Helene, L’Hermitage, and Linwood as well as the chemical plants of BASF and Shell in Geismar, I look at chemicals as a material to collapse space and time.

Introduction

In the following paper, I will first explore the history of the sugar plantation and petrochemical economy in Louisiana. Second, I will provide a specific example of sugar plantation lineage leading to petrochemical plant ownership. Third, I will discuss how these histories are entangled and fold on each other. Thus, I argue that by understanding chemicals in the landscape as persistent materials, we can understand temporality in a non-linear postcolonial framework.

Temporality is the way time is ordered and experienced. Anne Laura Stoler (2016) suggests there are multiple kinds of temporalities, such as rupture versus continuity. Where ruptures reflect distinct epochs and shifts in time and continuity represents seamless extensions and transitions. While tracking colonial presences, though, our colonized conceptions of time may inform the way we interpret the present and the past. Stoler (2016) instead uses a recursive analytic to describe how histories fold back onto themselves, revealing new contingent possibilities.

Stoler’s (2016) work feeds directly into the work of Michelle Murphy (2017) and the idea of materiality influencing colonial afterlives. In Murphy’s work, chemicals challenge the bounds of the body and the human. Murphy specifically draws on how PCBs have entered the human body through the pollution of the landscape to become persistent through time (2017). These inescapable entanglements and persistent materials are what the following of this paper revolves around.

History and Background

The sugar cane plantations of Louisiana were the driving mode of production and economic growth in the 19th century. Between 1820-1860, planters experienced rapid growth in the industrialization process of sugar. However, “Louisiana evolved as the last of the New World’s cane sugar colonies, and its industry combined the collected experience and suffering of plantation sugar production with lessons drawn from American slavery and industrialization” (Follett 2005:8). Due in part to the demanding cycles of sugar production and the horrific conditions of enslaved workers, the need for labor stability and consistent production drove the industrialization of cane processing and sugar production (Follett 2005:13-16).

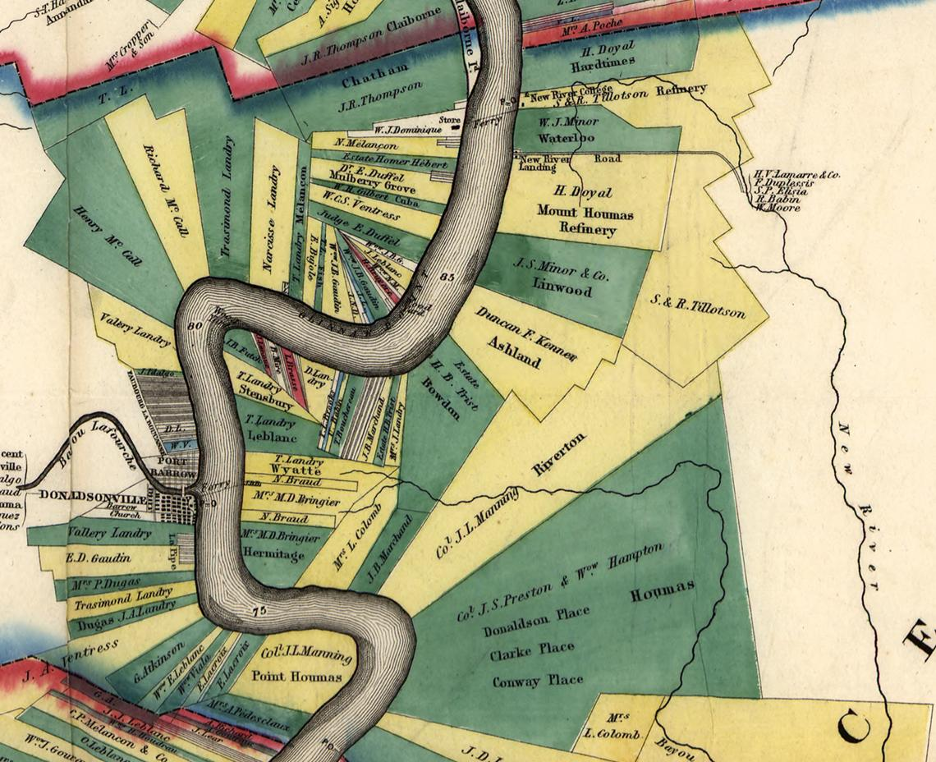

By 1805, the river bottomlands of South Louisiana had been transformed into a rising sugar production landscape (Follett 2005:19). In the early 19th century, demand and federal tariffs allowed planters to exploit the sugar market and the number of estates went “from 308 in 1827 to 691 in 1830” (Follett 2005:21) With tariff support, the sugar production expanded across South Louisiana with the core zone along the Mississippi River spanning between New Orleans and Baton Rouge (Follett 2005:21). In 1853, sugar planters in Louisiana produced a quarter of the world’s exportable sugar (Follett 2005:22). Sugar production did take a turn in the late 1840s as land, labor, and capital costs increased and federal tariff protections for sugar were reduced. This caused increased mergers between estates. “In 1850, the average sugar planter in Ascension Parish cultivated 460 acres. A decade later, fourteen fewer sugar planters recorded that 29,149 acres— approximately 800 acres per estate— lay under crop” (Follett 2005:32).

At the same time, the expansion of plantations caused a rise in enslaved populations. In 1830, one average plantation consisted of 52 enslaved peoples. In the 1850s, average plantations consisted of 85 enslaved workers, and “by the Civil War, most large sugar plantations listed as many as 110 enslaved African Americans on their inventories.” (Follett 2005:25-26) In Ascension parish specifically, enslaved persons outnumbered whites two to one (Follett 2005:26). Plantation landscapes have been a subject of anthropological, archaeological, historical, and geographical study. It has often been argued that Plantations are a panopticon based on Michel Foucault’s (1977) idea of prison panopticon. Scholars argue that the plantation is spatially organized for the social control of the enslaved black population (Marshall 2022; Nielson 2011; Singleton 2001; Kumar 2015; Davis 2016; Epperson 2000; Michelakos 2009)

From a postcolonial perspective, the plantation offers a place for reimagining the environment and ecologies. As the location of anthropogenic violence, plantations capture the capitalist nature of ecological simplification and progress and at the same time offer places of “multispecies resistance and resurgence” (Chao 2022:363). To envision the co-creation of life in these landscapes and the impacts of non-human forms draw on the work of Donna Haraway (2015), Anna Tsing (2012), and Catherine McKittrick (2013). McKittrick (2013) offers up the idea of futures within the plantation where opportunities emerge to contemplate survival. The rest of this paper will continue to think with her questions:

“What are some notable characteristics of plantation geographies and what is at stake in linking a plantation past to the present? What comes of positioning the plantation as a threshold to thinking through long-standing and contemporary practices of racial violence? If the plantation, at least in part, ushered in how and where we live now, and thus contributes to the racial contours of uneven geographies, how might we give it a different future?” (McKittrick 2013:4).

I continue to draw on these questions and thoughts of alternative ecologies (McKittrick 2013, 2020; Cervenak 2021; Haraway 2015; Tsing 2012; Barra 2023) as I draw out the relationships of place, time, and non-human actors.

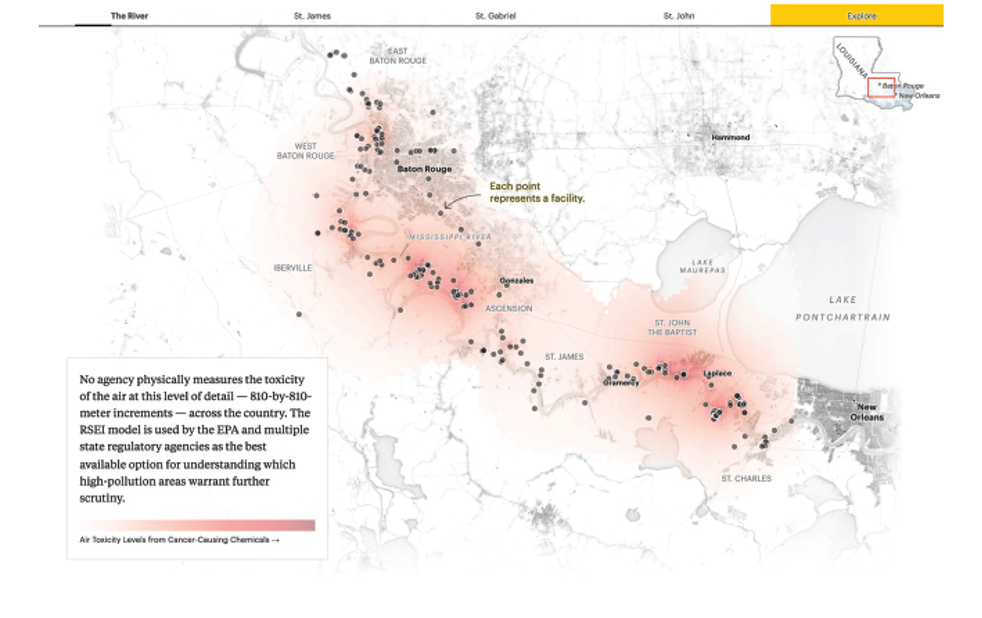

The area between Baton Rouge and New Orleans that was the core of sugar production in the 19th century is now home to “more than 150 petrochemical plants and petroleum processors” (Allen 2006:112). In the aftermath of the civil war, the Freedmen’s Bureau awarded small areas of land to black family groups in the area where they had previously been enslaved and worked. However, large plantation lands stayed in the hands of white owners. As a result, the region was made up of large blocks of land owned by a single owner with smaller separated communities of freed blacks and poor whites adjacent to the larger properties (Allen 2006). As chemical and petroleum companies moved into the region, the preferable land for building was large areas owned by a single owner. Thus, the smaller “African-American communities and petrochemical facilities came to exist in such close proximity along the river” (Allen 2006:113).

Initially attracted to the region for its access to transportation and ports as well as favorable treatment from Louisiana politicians, Mexican Petroleum (now Amoco) and Standard Oil (now Exxon) were the first companies to establish plants in the area. Despite the economic downturn of the 1930s, “the Gulf Coast experienced tremendous growth in both petroleum processing and chemical production” (Allen 2006:114). Decades later, in 1964, the African-American town of Geismar was sighted as the next location for major petrochemical development. By this time, there was multi-corporation cooperation making the region interconnected by infrastructure and piping and ideal for increased development. The list of corporations buying property along the river in Geismar included Mobil, MonoChem, BASF, Morton, Allied, and others.

The attraction to this area was not just based on the property availability and corporate cooperation/infrastructure but also the government assistance in the forms of little to no property taxes, Corps of Engineers work on levee stabilization, construction of state highways and bridges, and the lack of political pressure from the governor (Allen 2006). The biggest benefit to building and operating in Louisiana is the state’s corporate tax-exemption programs, which assist plants like Shell’s Norco facility and Exxon’s Baton Rouge refinery (Allen 2006). These two companies in particular “avoided paying over $175 million in taxes during the 1980s” (Allen 2006:117). This exemption dates to 1936 and has persisted into the present where Louisna grants the exemption status without local approval or input such that the lack of tax revenue has caused these local areas to be underfunded and lack access to basic resources (Allen 2006).

Case Study – Geismar, Ascension Parish, Louisiana

The case study I present here offers an opportunity to examine how the postcolonial landscape is shaped and changed over time. I specifically look here at how chemicals can change temporality and expose recursive sociohistorical elements of the landscape. To do this, I will delineate the landscape history of two chemical plants in Geismar, LA. These plants are situated on property that used to be large sugar plantations in Ascension Parish. Thus, I will begin with a lineage of plantation ownership before moving on to their present-day petrochemical plant counterparts and the persistent chemicals they produce.

The first plantation I followed the history of is Ashland-Belle Helene, or Ashland Plantation, also known as the Belle Helene or Ashland-Belle Helene Plantation. It may be evident already that this plantation is a result of property consolidation. Today, the entire property of the estate belongs to and is surrounded by the Shell Chemical, LP, Geismar plant (Couvillion 2015). In 1840 the Kenner brothers acquired the Oakland, Belle Grove, and Pasture Plantations. In addition to this consolidation, Duncan Kenner acquired land and property that included not only what was to be named the Ashland Plantation and mansion that he built for his wife, Anne Guillemine Nanine Bringier, but also the Bowden, The Houmas, the Hollywood, the Hermitage (as his wife was related to the Bringier family), the Fashion (home of his brother-in-law and partner General Richard Taylor), and Roseland plantations (“Bibliographical and Historical” 1892). The 1860 U.S. Census Slave Schedules for Ascension Parish, Louisiana (NARA microfilm series M653, Roll 427) includes the Kenner name and number of enslaved people associated with them. Duncan F. Kenner is associated with 473 enslaved people (Blake 2001).

The second plantation is the Hermitage, or L’Hermitage. Shortly after his marriage in 1812- to fourteen-year-old Louise Aglaé duBourg, Michel Doradou Bringier built the Hermitage on land given as a wedding gift by his father. At Bringier’s death in 1847, his second son, Louis Amédée, became owner of the plantation. In 1881 Duncan Kenner of Ashland-Belle Helene, who was married to Bringier’s daughter Nanine, purchased a part share of the plantation. He acquired full control from 1884 until his death in 1887 (“Bibliographical and Historical” 1892). The 1860 U.S. Census Slave Schedules for Ascension Parish, Louisiana (NARA microfilm series M653, Roll 427) includes the Bringier name and number of enslaved people associated with them. Louis A. Bringier held 144 enslaved people and M. L. Bringier (likely the first son) held 386 enslaved people (Blake 2001).

Linwood Plantation was owned by the J.N. Brown until his death in 1859 (“Bibliographical and Historical” 1892). Probate records of Brown (1807–1859), a wealthy sugar planter from Iberville Parish, Louisiana, contain primarily financial records related to the administration of his estate, which mentions legal and family ties to the families Ventress and Minor (Brown J. (1858-1871). The 1860 U.S. Census Slave Schedules for Ascension Parish, Louisiana (NARA microfilm series M653, Roll 427) includes the Brown, Ventress, and Minor names and number of enslaved people associated with them. John M. Brown held 105 enslaved people, John L. Minor held 193 enslaved people, Wm. J. Minor held 223 enslaved people, James A. Ventress held 88 enslaved people, and W.C.S. Ventress held 89 enslaved people (Blake 2001).

The petrochemical plants that have replaced these plantations in the present firstly include Shell Geismar. The facility uses ethylene feedstock to manufacture ethylene glycol and alpha olefins, chemicals that can be converted into plastic resins and polyester fibers. Linear alpha olefins are used to make polyethylene, synthetic lubricants, detergents, and waxes (Environmental Integrity Project 2022). The second major plant is BASF Geismar. BASF, which owns the complex, is an acronym that stands for Badische Anilin und Soda Fabrik, which is German for Baden Aniline and Soda Factory. Germany’s largest chemical company was founded by Friedrich Engelhorn in 1865. “Currently, the Geismar Complex is composed of 14 plants which produce ethylene oxide/glycols, aniline, acetylene, butanediol, and other chemicals and petrochemicals” (Environmental Integrity Project 2022).

As recently as April 7, 2022, BASF invited representatives from Ascension Parish, the River Road African American Museum, the United Houma Nation, and members of the descendant community to dedicate a new memorial at the BASF site in Geismar to those who were enslaved on what was previously Linwood plantation (Anderson 2022).

Discussion

Steiniger (2021) argues that there are connections of the petrochemical corridor in Louisiana to German industrialism. Because of this Steiniger argues that it is important to develop a “‘chemical cultural theory’ that seeks to observe the specific technicalities of modern materiality and the historical settings that enabled this” (265). Because chemicals have a significant materiality, the material and technical aspects are entangled with mechanisms of power (Steiniger 2021:265). Steiniger (2021) combines aspects of the study of the Anthropocene and contingencies with a material centered approach that I suggest is archaeological in perspective. In a material ontological turn, Stieniger (2021) places the chemicals (in his argument fertilizer) in an agentive role transforming history, landscape, and power.

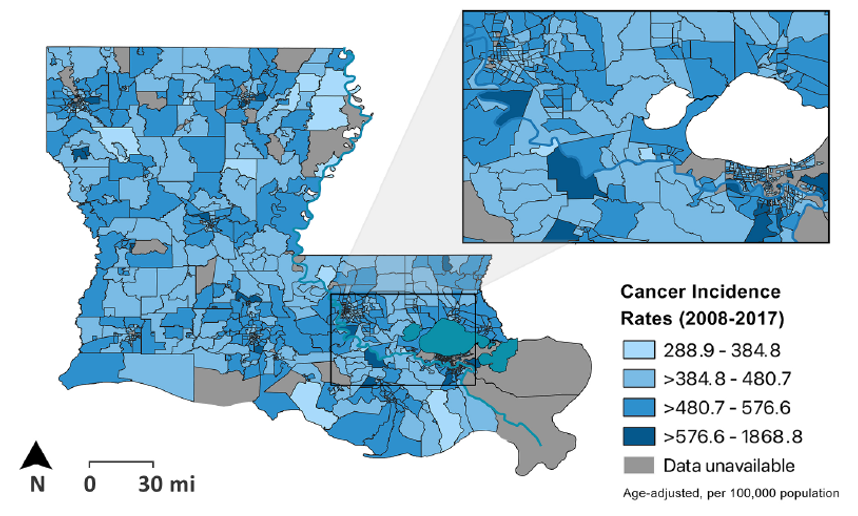

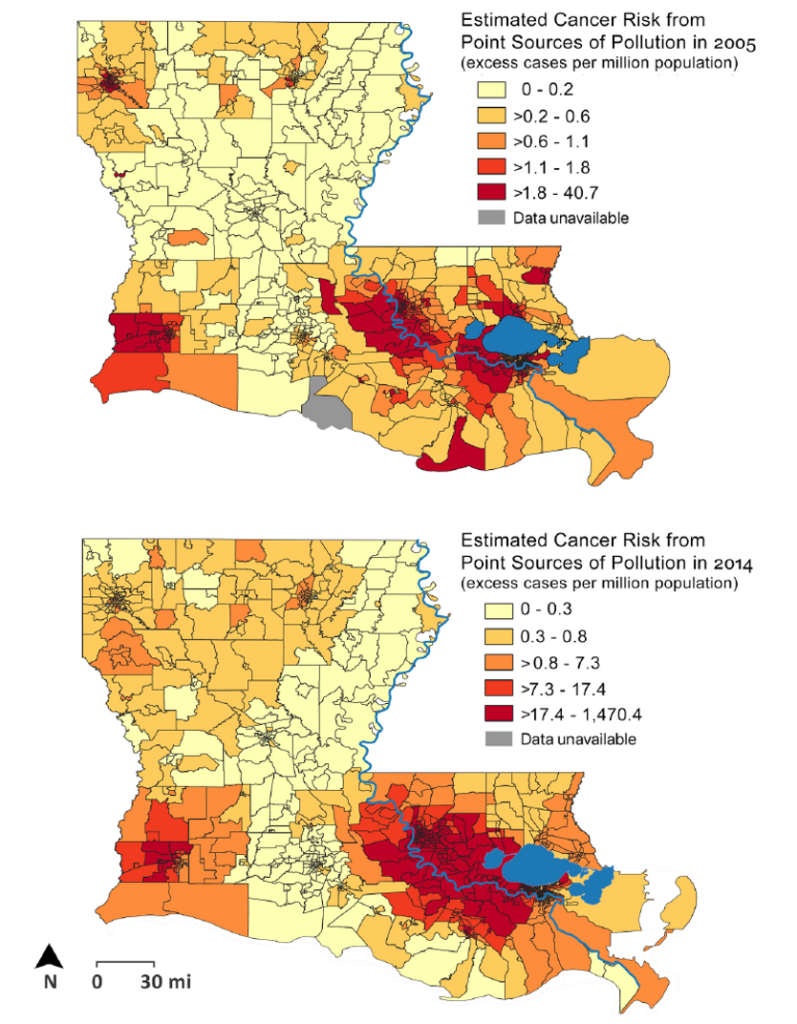

One persistent aspect of these chemicals that is felt and seen is in the pollution of the landscape and the health of the residents of the area. “According to a seven-parish survey of residents living within a mile of the river, where industry is most heavily concentrated, 35 percent suffer from respiratory problems, 21 percent from allergy problems, and 17 percent from other sinus problems, in addition to claims of elevated cancer rates” (Allen 2006:117-118). Terrell and St. Julien (2022) explore these claims of elevated cancer rates that residents of the area have long said they are disproportionately affected by. Their results (Figures 2 and 3) show that there is a higher cancer risk from air toxins and higher cancer incidence did affect black populations and impoverished populations, which tended to coincide (Terrell and St. Julien 2022:10).

The chemical presence and continued pollution in Cancer Alley (Figure 4) illustrate the chemical persistence as well as the way the chemical presence collapses temporality. Kang (2021) argues that the Plantationocene “firmly emplaces the machination and violence of the plantation in the present. As such, the material theorization of coloniality and the temporalization of the Plantation epoch helped give shape to the ongoing violence of Cancer Alley” (109). Because of this, the perception of time and place has consistently changed for the residents of the area. There is visual change with the surrounding influx of industrialization and slow death of the environment, which itself is a non-human actor part of the larger ecology. In addition, residents of the area have an underlying consciousness of their potentially shortened life-span. Time and the time spent in their homes affects them differently. Time is afforded differently because of the chemical conviviality residents endure.

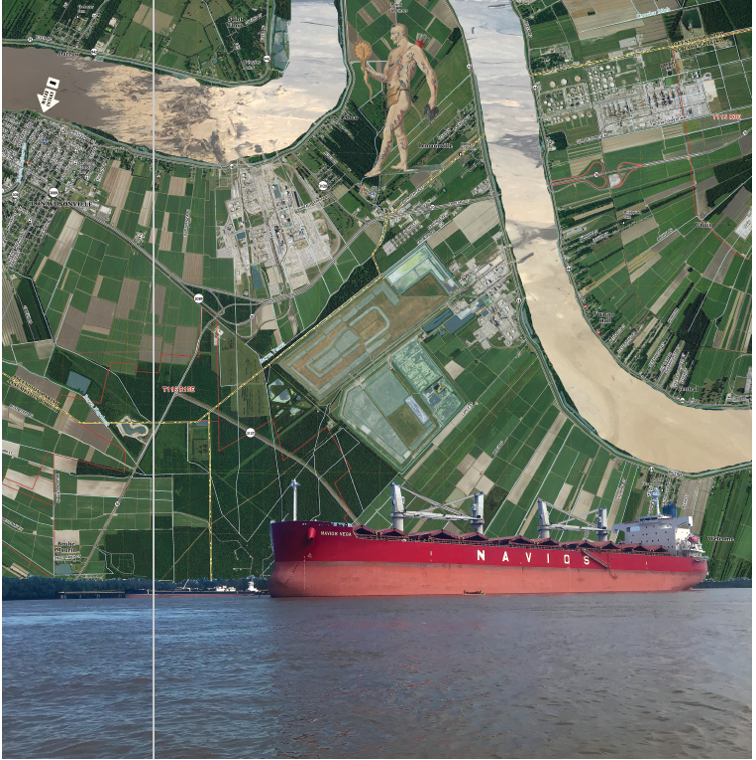

In addition, the chemical landscape provides us an opportunity to interrogate recursivity in the history and use of the landscape. Returning to colonization and plantations while connecting with the present allows us to see webs of contingencies. Indigenous artist, Monique Michelle Verdin, uses collages to collapse time and demonstrate colonial and postcolonial erasure on the landscape. She describes this work as: “The collages illuminate how these sites are variously represented or simply erased, and how the challenges of today are founded in colonialism, with rapacious multinational corporations and international financing fueling violations against basic human rights like clean water” (Verdin 2020:80).

Orienting us within the native language she describes what is now Baton Rouge: “Istrouma is both a place and a symbol, a red stick, le bâton rouge, used to mark territorial lines, acknowledging the Houma nation’s hunting grounds to the north and the rights of the Bayou-goula tribe to the south, or thus it was recorded in the journals of colonizers” (Verdin 2020:81). Geismar is not represented within her collages but sits on the eastern Bank of the Mississippi River between Plaquemine Island and Donaldsonville: Point Houmas, which I include in this paper. She follows the river to “Bvlbancha (“place of many languages” in Choctaw) is the original name of the lower Mississippi River that was successfully rebranded “Nouvelle Orleans” by French colonizers. Plaquemine means persimmon in Mobilian, a pantribal pidgin language and the predominant trade jargon spoken in the territory when the colonizers arrived.” (Verdin 2020:83).

The collage of Plaquemine Island (Figure 5) connects it to the long history of extraction in the region. As she states, “In the early years of colonialism, from the late seventeenth century through the 1920s, the fur trade fueled such a get-rich-quick furor that beavers, minks, muskrats, and other furry creatures nearly went extinct” (Verdin 2020: 83). Second the collage (Figure 6) of Donaldsonville: Point Houmas represents “the historic distributary La Fourche des Chitimatchas (the fork of the Chitimatcha), also called the River of the Chitimatcha, [which] is known today as Bayou Lafourche” (Verdin 2020:84). This area was historically an area that connected a web of bayous to Indigenous settlements, a place where enslaved peoples found food security, and where sugar planters began to claim land after the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 (Verdin 2020).

Conclusion

Throughout this paper, I have worked to show that the landscape of Ascension Parish offers a case study to reconsider chemical materiality. As persistent and invasive artifacts of human activity ion the region, their presence and agency shape the ecosystem in new and different ways. In addition, their role in the present is underscored by contingencies of the postcolonial world. Because of this, chemical artifacts also change our temporality. They represent a postcolonial present and past interacting in one locality.

I want to end this paper by turning to the questions posed by McKittrick in “Plantation Futures”:

“What are some notable characteristics of plantation geographies and what is at stake in linking a plantation past to the present? What comes of positioning the plantation as a threshold to thinking through long-standing and contemporary practices of racial violence? If the plantation, at least in part, ushered in how and where we live now, and thus contributes to the racial contours of uneven geographies, how might we give it a different future?” (McKittrick 2013:4).

Using the case study, I have presented, what at stake in linking a plantation past to the present is a different understanding of temporality and ecologies. Positioning the plantation as a threshold to thinking through long-standing and contemporary practices of racial violence allows us, as Verdin (2020) shows, to see the hidden parts of the post-colonial world and the continued racial inequities that manifest from those parts. Finally, McKittrick (2013) invites us to consider a different future. By reckoning with the past, we begin to shape how we can change the future, but with our understanding of a non-linear temporality, we can also consider how the future we design will fold back on the past and where we are in the present.

Works Cited

Allen, B. L. (2006). Cradle of a revolution? The industrial transformation of Louisiana’s lower Mississippi river. Technology and Culture, 47(1), 112-119.

Anderson, S. J. (2022, April 8). BASF Dedicates Memorial to honor enslaved of former plantation. Gonzales Weekly Citizen. Retrieved April 27, 2023, from https://www.weeklycitizen.com/story/news/2022/04/08/basf-dedicates-memorial-honor-enslaved-former-plantation/9510302002/

Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Louisiana: Embracing an Authentic and Comprehensive Account of the Chief Events in the History of the State, a Special Sketch of Every Parish and a Record of the Lives of Many of the Most Worthy and Illustrious Families and Individuals …. (1892). United States: Goodspeed publishing Company.

Blake, T. (2001) Ascension Parish, Louisiana. Largest Slaveholders from 1860 Slave Census Schedules and Surname Matches for African Americans on 1870 Census. Transcribed from the 1860 U.S. Census Slave Schedules for Ascension Parish, Louisiana (NARA microfilm series M653, Roll 427)

Brisbois, B. W., Spiegel, J. M., & Harris, L. (2019). Health, environment and colonial legacies: situating the science of pesticides, bananas and bodies in Ecuador. Social Science & Medicine, 239, 112529.

Brown J. (1858-1871) James N. Brown Papers, 1855-1879, Iberville, Ascension, Plaquemines, and East Baton Rouge Parishes, Louisiana. In Records of Ante-bellum Southern Plantations from the Revolution Through the Civil War. Series G: Selections from the Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin. Part 5: Natchez Trace Collection— Other Plantation Collections. University Publications of America.

Cervenak, S. J. (2021). Black gathering: Art, ecology, ungiven life. Duke University Press.

Chao, S. (2022). Plantation. Environmental Humanities, 14(2), 361-366.

Couvillion, E. (2015, June 17). Ashland-Belle Helene in Ascension Parish restored to former glory; Historic Plantation Home owned by Shell Chemical. NOLA.com. Retrieved April 27, 2023, from https://www.nola.com/news/communities/ashland-belle-helene-in-ascension-parish-restored-to-former-glory-historic-plantation-home-owned-by/article_be6d82c9-f2ec-54fb-ab6f-9960dc41df05.html

Davies, T. (2018). Toxic space and time: Slow violence, necropolitics, and petrochemical pollution. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 108(6), 1537-1553.

Davis, C. (2016). The panoptic plantation model: geographical analysis and landscape at Betty’s Hope Plantation, Antigua, West Indies.

Environmental Integrity Project. (2022). Oil and gas watch: BASF Geismar Chemical Complex. Oil and Gas Watch. Retrieved April 27, 2023, from https://oilandgaswatch.org/facility/5156

Environmental Integrity Project. (2022). Oil and gas watch: Shell Geismar Chemical Plant. Oil and Gas Watch. Retrieved April 27, 2023, from https://oilandgaswatch.org/facility/5156

Epperson, T. W. (2000). Panoptic plantations. Lines that Divide: Historical Archaeologies of Race, Class, and Gender, 58.

Follett, R. J. (2005). The sugar masters: planters and slaves in Louisiana’s cane world, 1820-1860. LSU Press.

Foucault, M. (1977) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Trans. A. Sheridan. New York: Vintage.

Haraway, D. (2015). Anthropocene, capitalocene, plantationocene, chthulucene: Making kin. Environmental humanities, 6(1), 159-165.

Kang, S. (2021). ” They’re Killing Us, and They Don’t Care”: Environmental Sacrifice and Resilience in Louisiana’s Cancer Alley. Resilience: A Journal of the Environmental Humanities, 8(3), 98-125.

Kumar, M. (2015, January). Coolie Lines: A Bentham Panopticon Schema and Beyond. In Proceedings of the Indian History Congress (Vol. 76, pp. 344-355). Indian History Congress.

Marshall, L. W. (2022) Slavery, Space, and Social Control on Plantations, Journal of African Diaspora Archaeology and Heritage, 11:1, 1-4, DOI: 10.1080/21619441.2022.2079251

McKittrick, K. (2013). Plantation futures. Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism, 17(3 (42)), 1-15.

McKittrick, K. (2020). Dear science and other stories. Duke University Press.

Michelakos, J. (2009). The Caribbean Plantation: Panoptic Slavery and Disciplinary Power.

Murphy, M. 2017. Afterlife and Decolonial Chemical Relations. Cultural Anthropology 31(4): 494-501.

Nielsen, C. R. (2011). Resistance Is Not Futile: Frederick Douglass on Panoptic Plantations and the Un-Making of Docile Bodies and Enslaved Souls. Philosophy and Literature, 35(2), 251-268.

Persac, M. A., Norman, B. M. & J.H. Colton & Co. (1858) Norman’s chart of the lower Mississippi River. New Orleans, B. M. Norman. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/78692178/.

Singleton, T. A. (2001). Slavery and spatial dialectics on Cuban coffee plantations. World Archaeology, 33(1), 98-114.

Steininger, B. (2021). Ammonia synthesis on the banks of the Mississippi: A molecular-planetary technology. The Anthropocene Review, 8(3), 262-279.

Stoler, A. L. 2016. Duress: Imperial Durabilities in Our Times. Durham NC: Duke University Press. Pp.3-8, 24-27.

Terrell, K. A., & St Julien, G. (2022). Air pollution is linked to higher cancer rates among black or impoverished communities in Louisiana. Environmental Research Letters, 17(1), 014033.

Tsing, A. (2012). Unruly Edges: Mushrooms as Companion Species. Environmental humanities, 1(1), 141-154.

Verdin, M. M. (2020). Cancer Alley. Southern Cultures, 26(2), 80-95.