A World Beyond Imagination?

Day not so strenuous. Forms go faster. Also discover some mistakes made yesterday. Hope they get their sugar. D’Arcy McNickle, 5 May 1942

Sugar ration cards. The Tohono O’odham Tribal Cattle Program. Migrant farms. Cooperatives. Lectures on nutrition and health. These things, all of which D’Arcy McNickle wrote about as he traveled through the Southwest as a representative of the Office of Indian Affairs in the spring of 1942, might seem disparate.

In reality, they all speak, like McNickle’s garden writing, to the ways in which food shapes our lives. The quote featured here speaks to McNickle’s efforts to assist Native  workers in migrant labor camps register for sugar rations issued by the federal government after imports collapsed shortly after U.S. entry into World War Two. His references to cattle programs, cooperatives, migrant labor, and lectures on nutrition and health in still other entries further speak to the ways that tribal nations sought to build their economies and individuals sought to provide for their families in the midst of drought and the ongoing Great Depression.

workers in migrant labor camps register for sugar rations issued by the federal government after imports collapsed shortly after U.S. entry into World War Two. His references to cattle programs, cooperatives, migrant labor, and lectures on nutrition and health in still other entries further speak to the ways that tribal nations sought to build their economies and individuals sought to provide for their families in the midst of drought and the ongoing Great Depression.

Thinking about all the insights into food and foodways evident in McNickle’s diary led us to ask whether he could have imagined a world like ours–one in which community gardens, food sovereignty, Indigenous foodways, and traditional ecological and ethnobotanical knowledge have become not only powerful methods of individual and collective empowerment in Native America but also increasingly mainstream methods of addressing food inequality and the climate crisis. Of one thing we feel certain: local people, scientists, and academicsalike are doing so, like McNickle would have, with a growing awareness of the value of Indigenous knowledge and of the need for local community members to take the lead. How does food shape your experiential world and what are your foodways?

Thinking about all the insights into food and foodways evident in McNickle’s diary led us to ask whether he could have imagined a world like ours–one in which community gardens, food sovereignty, Indigenous foodways, and traditional ecological and ethnobotanical knowledge have become not only powerful methods of individual and collective empowerment in Native America but also increasingly mainstream methods of addressing food inequality and the climate crisis. Of one thing we feel certain: local people, scientists, and academicsalike are doing so, like McNickle would have, with a growing awareness of the value of Indigenous knowledge and of the need for local community members to take the lead. How does food shape your experiential world and what are your foodways?

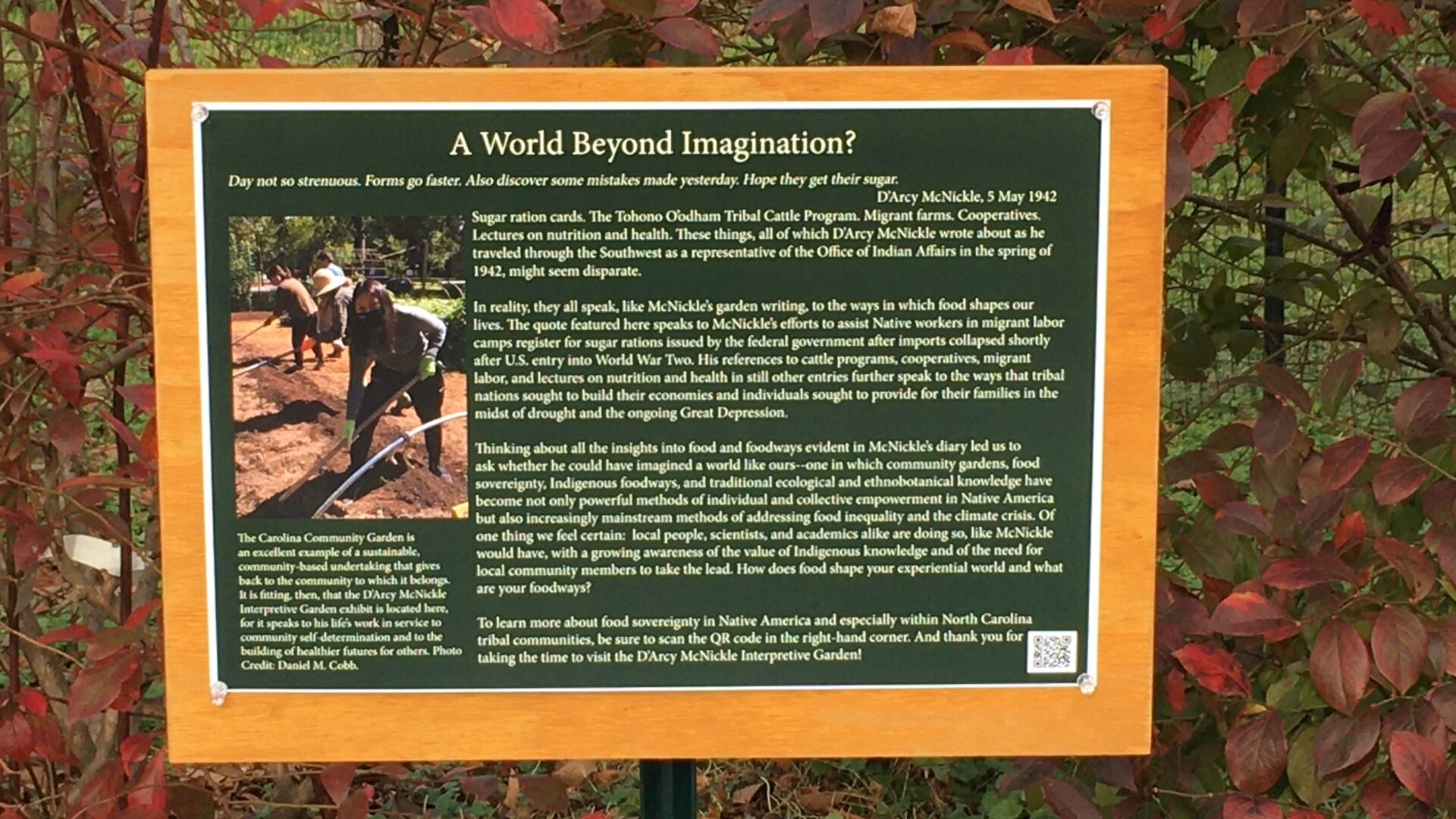

The Carolina Community Garden is an excellent example of a sustainable, community-based undertaking that gives back to the community to which it belongs. It is fitting, then, that the D’Arcy McNickle Interpretive Garden exhibit is located here, for it speaks to his life’s work in service to community self-determination and to the building of healthier futures for others.

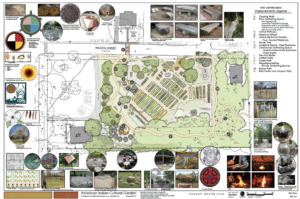

The UNC American Indian Center is currently creating an American Indian Cultural Garden (AIGC) on UNC’s campus. The AICG will be a haven for Indigenous plants and food pathways meant to revitalize the Native plant species and produce in the local area. The landscape is set to feature various installations that represent aspects of Indigenous culture and traditional food systems. Specific of the garden will hopefully include a crossing walk, entry gathering space, Native pathway, medicine wheel, Native medicinal garden housing the Four Sacred Medicines, a prayer tree, sculpture fence/deer inclosure, ceremonial gathering space, fire and water, cattail gate, snake path, woodland setting, return path, and red cedar and yaupon holly trees. This directly contributes to the revitalization and reclamation of Indigenous food sovereignty and the right to local, fresh produce for and by Indigenous peoples here at UNC. The AICG will enable a bridge between the abundance and richness of American Indian and Indigenous cultures in combination with the resources found in Carolina’s research, education and service to flourish for years to come.

Contributors: Caroline Horne, Zoey Locklear, Kaylee Ransom, Mariana Rodriguez, and John Zuluaga-Romero

Original Text: Samara Airy Perez Labra and Professor Dan Cobb