Visual arts allow the expression of subaltern knowledge when traditional modes of knowledge-making (the university, the government, etc.) are controlled by the colonial state. When we make art we are able to pull at heartstrings in a way that traditional forms of critique may not be able to do. Art can be a universal language: where obstacles such as translation and accessibility arise in interpreting works such as academic articles, art can heal wounds. Art is often seen as dangerous because it can lead to ideas, be it ideas of liberation or ideas of equality, that the colonial state would rather suppress to maintain its power. I hope you enjoy these works of colonial critique!

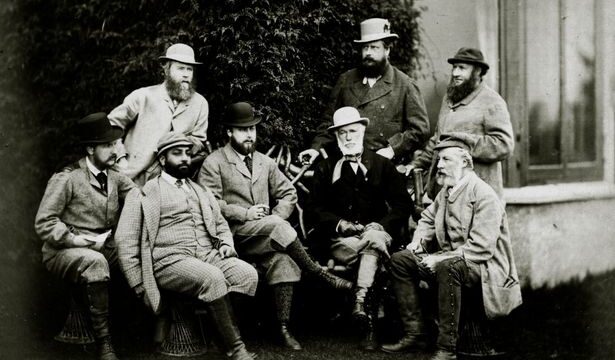

Vitr.(Indian) Woman by Durga Sreenivasan

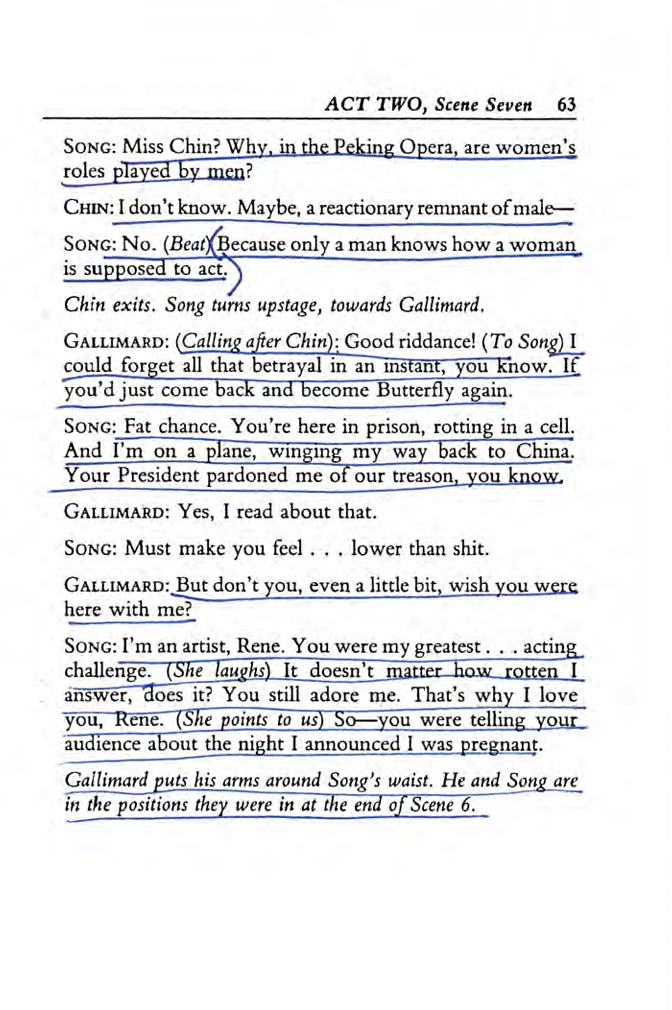

“Vitr. (Indian) Woman,” Ink upon Tea-Stained Paper (18 x 24 in.)

Summary:

Britain tore apart Indian land, leaving centuries of political violence in its wake. The care and effort put into the British governing system was not offered to the South Asian continent. Women and men were shipped off, miles away by boat. Woman were raped and assaulted as their villages were pillaged. All for tea, spices, and luxury goods. Thus, this piece is tea-stained, a method which I first encountered in the work of my uncle, Nitin Mukul. The tea-stain symbolizes that the the tea industry in India had underlying and long-lasting consequences. In Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, he writes step-by-step instructions on how to recreate his figure’s proportions. I used these instructions to create my piece, with hopes of illiciting a response to the recognizable artwork. Da Vinci’s work is an icon in Western work… perhaps it’s been decolonized.

Deep-dive:

Tea as a Technology of Rule

In chapter two of “Science and Colonial Expansion,” Lucille Brockway provides broader context on how plantations were used as a technology of rule in the context of colonial expansion.

The tea industry was the most critical economic venture for Britain in India during the colonial period, and it was a tool for colonization in the region. Plantations required the use of technology, and, as Brockway notes, the implementation of scientific knowledge in order to produce raw materials for export to Europe (Brockway 2002). Furthermore, the tea industry in India was intertwined with colonial policies of land ownership and control. Brockway explains that social domination was pervasive throughout plantations, and the tea industry was no exception. British colonizers established tea plantations on land that had previously been owned and cultivated by Indian farmers, and they used their military and economic power to maintain control over the region.

The tea industry’s social and cultural impacts reverberated throughout the subcontinent. As Brockway notes, the establishment of plantations brought with it a new social order entrenched with discrimination, racial hierarchies, and gender inequalities (Brockway 2002). The tea industry in India was staffed largely by Indian laborers, who were subjected to harsh working conditions and low wages (Chatterjee 2001). The industry also reinforced harmful stereotypes, as British colonizers constructed an image of India as a place of exoticism and mystery, and Indian tea became a symbol of British colonial power and superiority.

The tea industry in India was a significant technology of rule for the British during the colonial period. It relied on scientific and technological innovations to establish and maintain control over the region. This control and the oppression it permeated was experienced particularly by women.

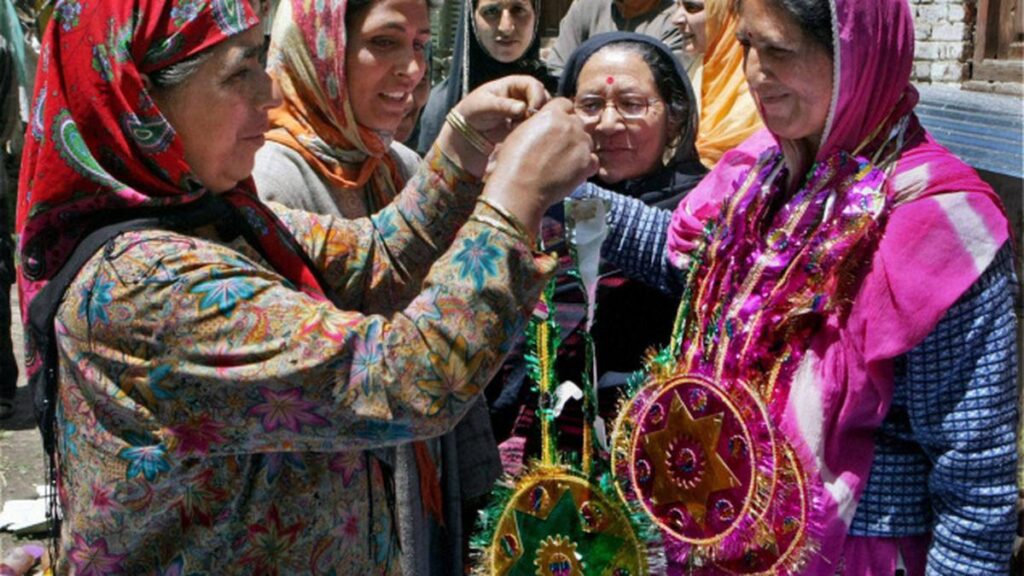

Tea & Postcolonial Feminism

According to Jayeeta Sharma’s “Empire’s Garden,” the tea industry in India played a significant role in generating profits for British companies and contributing to the growth of the British Empire. However, this growth came at a cost for Indian women, who severely suffered from negative social and economic impacts. One of the most vulnerable groups affected by the colonial project, women often endured sexual violence under colonialism (Sharma 2011). As explained by Eric Young in “Postcolonial Feminism,” women were among the most vulnerable groups affected by the colonial project, and they often suffered from sexual violence and other forms of oppression under colonialism (Young 2008). The establishment of tea plantations, particularly in Assam and north India more broadly, was a key element of British colonial policy, as it provided a lucrative commodity that could be exported to Britain and other parts of the world (Sharma 2011).

Another author, Piya Chatterjee, emphasizes in “A Time for Tea,” that the product that brought Britain immense prosperity had horrific social, economic, and environmental impacts on the region (Chatterjee 2001). Sexual degradation and violence were simply an added dimension of this story (Sharma 2011).

As a woman whose family history is rooted in rural India, I can only feel the pain of the women whose bodies have become objects. Britain’s need for capital and luxurious products trumped basic human rights. This violence is haunting. However, this piece is not to reflect some form of martyrdom or pity – rather, doing this research has helped me expand on my knowledge and think about how I, and we as college students, can use our privilege for good. I, for one, am not faced by certain obstacles that low-caste Indians face, and understanding the unique discrimination and violence that low-caste Indians have endured historically are essential in this piece.

Author Piya Chatterjee, in “A Time for Tea,” hones in on the added marginalization of lower- individuals: caste discrimination led to the intensification of labor exploitation where upper-caste Indians had more control in plantations (Chatterjee 2001). Although caste was not created under the British, they further systematized the caste system. In understanding this artwork, we cannot overlook the legacy of colonial rule that Dalit Indians continue to face. Ten Dalit women every day are reportedly raped, and Dalit women who are survivors of sexual assault face intersectional oppression, that of being a Dalit alongside being a woman (Soutik 2020).

The tea industry in India was detrimental to the well-being of women, who were subject to sexual violence and low wages. These gendered impacts of colonialism and capitalism highlight the need for feminist and anti-colonial approaches to social and economic development, which I hope to explore in my further work.

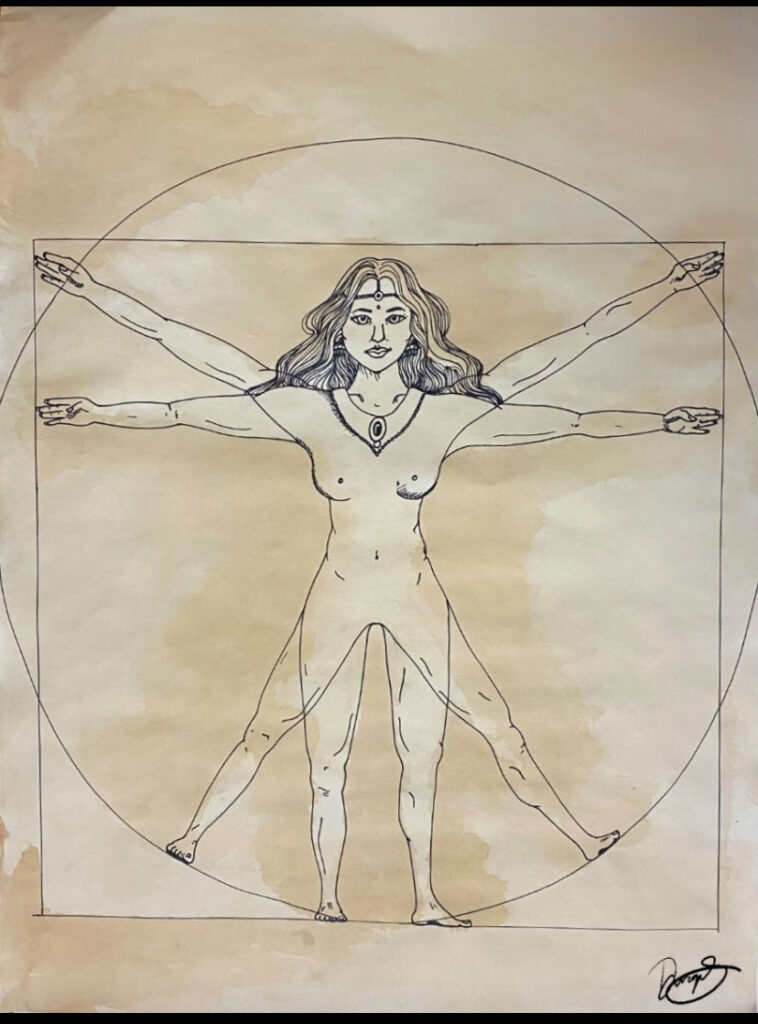

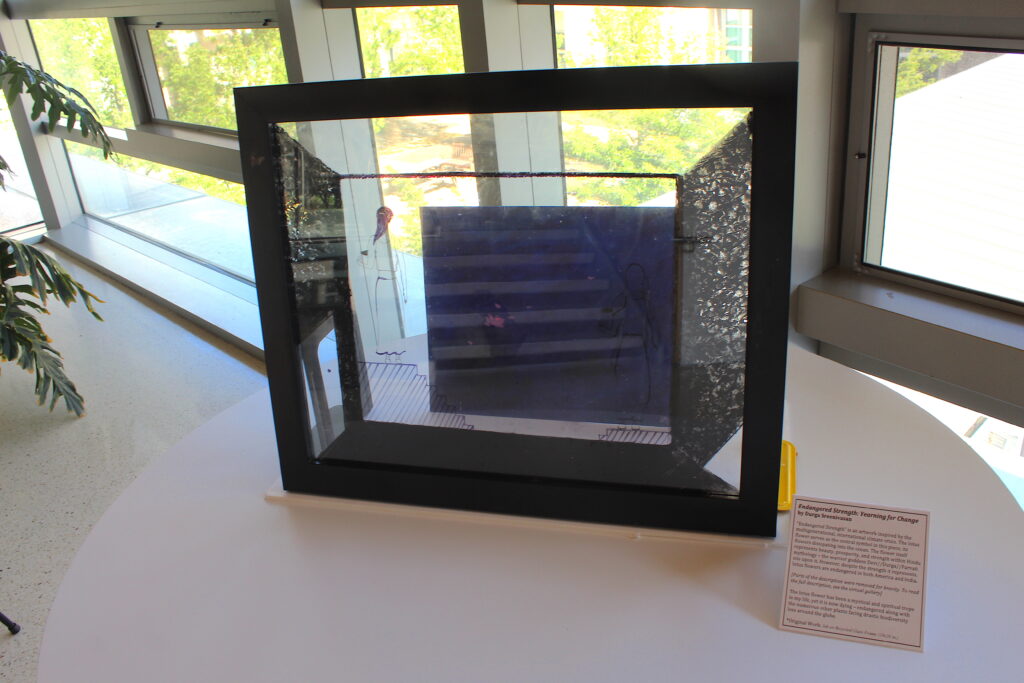

Endangered Strength: Yearning for Change by Durga Sreenivasan

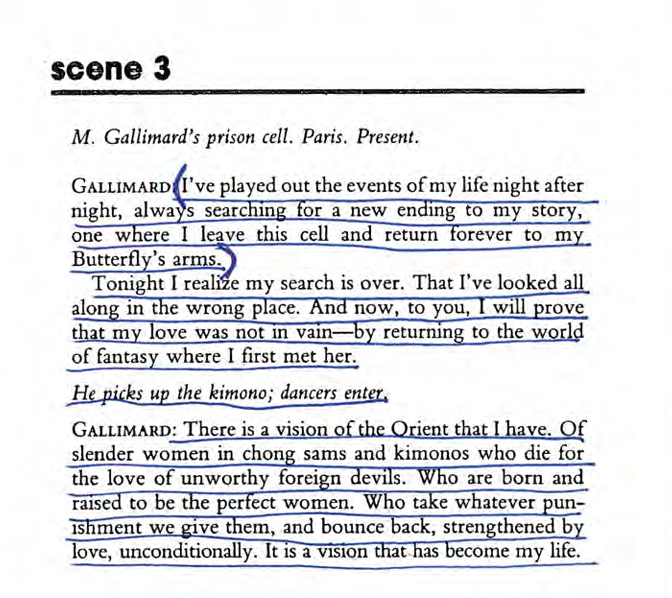

“Endangered Strength,” Acrylic and Ink on Recycled Glass Frame (18 x 22 in.)

Summary:

“Endangered Strength” is an artwork inspired by the multigenerational, international climate crisis. The lotus flower serves as the central symbol in this piece.The flower itself represents beauty, prosperity, and strength within Hindu mythology – the warrior goddess Devi//Durga//Parvati sits upon it. The lotus flower has been a mystical and spiritual trope in my life, yet it is now dying – endangered along with the numerous other plants facing drastic biodiversity loss around the globe due to climate change (Sivaramakrishnan 2009; Mooney 2021).

Deep-dive:

Environmental Injustices

The ink drawing on the glass frame depicts two women. The woman on the right is dressed in Western attire, while the woman on the left is dressed in classical Indian sari – placed in America and my ancestral home of Kerala, India respectively. The woman on the right is standing on a higher pedestal to represent the unequal situations in the U.S. and in India. Additionally, the throes of the climate crisis is hurting populations in emerging countries (the majority of which are in the Global South) at a disproportionate rate. A statement from the United Nations COP26 reads: “While no one is safe from the health impacts of climate change, they are disproportionately felt by the most vulnerable and disadvantaged.” (UN News, 2021)

Colonialism & Biodiversity Loss

The two women in the drawing represent the beauty of nature and the need for its preservation. Lotuses, with their elegant form and rich symbolism, serve as a metaphor for the endangered state of the natural world. This artwork is a call to action to protect the lotus flower, which is currently facing endangerment in Kerala, India and America. According to The Times of India, lotus farming in Kerala is being threatened by climate change and pollution particularly. Due to the increasing temperatures and erratic rainfall, lotus cultivation has become a challenge for farmers. Furthermore, industrial pollution (an aftereffect of colonialism) and waste have polluted the waters where lotus plants grow, leading to their decline (The Times of India, 2019).

Similarly, lotus plants in America, particularly in the southeast region, are facing habitat loss due to urbanization and agricultural expansion. The plant’s natural wetland habitats have been drained or filled for development, leading to the decline of the lotus populations in these regions (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service).

Colonialism has played a significant role in the current state of biodiversity loss and climate change. The exploitation of resources, including land and labor, by colonial powers has led to ecological degradation and environmental injustice. Industrialization has specifically fueled the loss of biodiversity, through infringing on land and creating harsh conditions that mitigate the chances of survival of plants and animals (Lopez, 2021). Understanding this crisis has brought me immense sadness – something only art, in its ability to display the ineffable, has allowed me share.

“Endangered Strength” is a call to action to protect the lotus flower and the ecosystems they support. I urge viewers to take action to address the climate crisis and support vulnerable communities who face the disproportionate impact of climate.

Untitled. by Durga Sreenivasan

“Untitled,” Acrylic on Canvas, (12 x 16 in.)

In preparing the previous two pieces, I included heavy theory and selfishly interpreted my own pieces of art. Here, I’d like to explore the idea of art as a blank slate: what does this piece mean to you? One fact about this art piece is that the large black dots on the left hand side were thumb prints placed by a few of my people of color (POC) friends. I hope to see a comment or two below!

Bibliography

Biswas, Soutik. “Hathras Case: Dalit Women Are among the Most Oppressed in the World.” BBC News, BBC, 6 Oct. 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-54418513.

Brockway, Lucile. 2002. Science and Colonial Expansion. Yale University Press.Ch.2.

Das, B., & Hossain, S. M. D. (2023). Ecofeminist Concerns and Subaltern Perspectives on ‘Third World’ Indigenous Women: A Study of Selected Works of Mahasweta Devi. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 25(2), Article 2.

Ecovision Law. (April 6, 2021). How Colonialism is Fueling the Biodiversity Crisis and Why a Genuine Commitment to Reconciliation is Urgently Required. Ecovision Law. https://www.ecovision-law.ca/blog/how-colonialism-is-fueling-the-biodiversity-crisis-and-why-a-genuine-commitment-to-reconciliation-is-urgently-required

Liboiron, Max. Pollution is Colonialism. (May 2021). Duke University Press. https://www.dukeupress.edu/pollution-is-colonialism

Mooney, Joseph. University of Michigan Matthaei Botanical Gardens and Nichols Arboretum. (June 28, 2021). Native Plant of the Week: American Lotus. https://mbgna.umich.edu/native-plant-of-the-week-american-lotus/

Mukul, N. (Artist). (n.d.). Chandelier 3 A [Photograph]. artnet. https://www.artnet.com/artists/nitin-mukul/chandelier-3-a-0ZgT7keqbOYHxVMvQACdsA2

Sharma, J. (2011). Empire’s Garden: Assam and the Making of India. Duke University Press. https://www.academia.edu/43619794/Empires_Garden_Book_by_Jayeeta_Sharma

Sivaramakrishnan, Parameswaran. “Rare Lotus under Threat in India.” BBC News, 17 Sept. 2009, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/8269273.stm.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. (n.d.). American lotus (Nelumbo lutea). https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp0/reports/ad-hoc-species-report?kingdom=P&status=E&status=T&status=EmE&status=EmT&status=EXPE&status=EXPN&status=SAE&status=SAT&mapstatus=3&fcrithab=on&fstatus=on&fspecrule=on&finvpop=on&fgroup=on&ffamily=on&header=Listed+Plants

UN News. (October 27, 2021). UN aid chief warns of ‘dire and worsening’ situation in north-eastern Nigeria. UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/10/1102702