by Ila Chilberg

“Taking ink beneath the skin helps erase the historical damage of betrayal and pain inflicted by others, because it is a form of permanent medicine”

-Lars Krutak (Vogue 2022)

Medicine. Created by Indigenous hands for Indigenous peoples, tattooing serves as a permanent reclamation of both body and culture for those whose history is marred by colonial oppression. By analyzing the practice of traditional tattoo amongst Indigenous American women, I argue that bodily adornment diffuses colonial means of recognition through the revitalization and recommunalization of Indigenous culture, and the reclamation of bodily autonomy. Drawing on epistemological theory inspired by the writing of Glen Coulthard and Arturo Escobar, I situate this work as an exploratory venture into how bodily adornment asserts themes of diaspora, pluralism, and the politics of recognition. Through the reassessment of colonial documentation and introduction of subaltern perspectives this work will utilize Indigenous women’s voices as the primary means through which cultural revitalization establishes continuance. Despite an onslaught of institutionalized erasure and objectification, Indigenous women reclaimed the North American movement of traditional tattoo and are utilizing permanent ink as an assertion of presence and opposition towards colonial modes of recognition. Furthermore, through the employ of social media, women such as Lyn Risling, Stephanie Big Eagle, and Jody Potts-Joseph have capitalized on the ever-increasing digitization of the global network to advocate for Indigenous recognition and educate the general populace.

To properly assess indigenous tattoo practice, it is necessary to contextualize how ritual adornment intersects with theoretical understandings of diaspora, temporality, pluralism, and epistemology. As outlined in the work of Vera Parham, Indigenous diaspora functions as an “[implied] cultural construction and a state in flux” embodying loss, retention, agency, “the connections a community of people maintain over distance”, “some sense of isolation and belief in separation from the majority of society”(Partham 2014: 318). Furthermore, the resulting severance from ancestral territory has resulted in an “age of unsettlement” for many native individuals whose disconnection has forced many to reevaluate more individualized “territories of existence”(Escobar 2018: 200). The question becomes, if the body serves as the sole directing current for understanding coexistence between multiple cultural spheres, how then can it undergo modification to suit this need? How then, when a collective of individuals experience “the more or less unconcealed, unilateral, and coercive nature of colonial rule” do these populations rewrite their own forms of recognition regardless of what is pre-established for them (Coulthard 2014: 3)?

Likewise, anthropologists in line with the work of Ann Stoler fixate on temporality and postcolonial experience, fixating their view on “ruins and ruination”, the ways in which colonial systems are embodied along a nonlinear time frame (Stoler 2016: 340). “Ruins” are conceptualized as “sites of reflection”, in this instance Indigenous bodies and culture, that are perceived to be “beyond repair and in decay” (Stoler 2016: 347). On the other hand, “Ruination” is “a condition to which one is subject, and a cause of loss” (Stoler 2016: 350). Together, these two principles define the compounding influence of historical action into the modern subconscious and society. However, while this principle does properly address temporality in postcolonial thought, it regards ruins as beings in stasis, removed of agency, and without potential for repossession. From this, I argue that when physical bodies are subject to ruination but capable of agentive action, there is the potential for reclamation, the condition to which one obtains autonomy from ruin, and revitalization, the cause for repair and recovery.

In order to not fall prey to the colonial rhetoric of Indigenous cultural death, it is of utmost importance to both detail the history of Native American practice, to reevaluate these histories through the inclusion of Indigenous ways of knowing, and to emphasize their continuance through their adaptation in the present day. Culture historians fixated on adornment have often neglected Indigenous history in their accounts of American tattoo practice. This focus has propagated a colonized lens of tattoo history as a whole and subsequently categorized the practice as one “primarily derived from its ability to outrage members of conventional society” (Sanders & Vail 2008:162-163). Rather than adopt Indigenous principles of tattoo as a means for healing and integration into native communities, the American tattoo industry classified the practice as one intended for rebellion and ostracization. Of the literature which does include accounts of Indigenous tattoo practice, the overwhelming body considers its expression as but one ruin resulting from colonization (Stoler 2016: 347). Further, this scholarship often fails to acknowledge tattoo culture outside of Inuit women or Native Alaskan women, and consistently devalues the usage of oral history in its account. While Inuit practice is vital, the vast cultural multiplicity that encapsulates Native American experience cannot be defined by one individual community. Likewise, to do so would cater to the enforced narrative of cultural homogeneity central to colonial forms of recognition and would ultimately devalue the individual means through which communities such as the Haida, Karuk, Ojibwe, and Dakota nations are establishing their own means of reclamation (Coulthard 2014: 2). Further, the reinsertion of oral history into analytical thought addresses the matter of understanding how Indigenous populations render their own forms of knowing during periods of consistent recommunalization and unsettlement (Escobar 2018: 200). All things considered, to properly analyze the means by which reclamation and revitalization are incorporated into Indigenous women’s practice of tattoo, it is pivotal that their voices and understandings are placed at the forefront of academic focus.

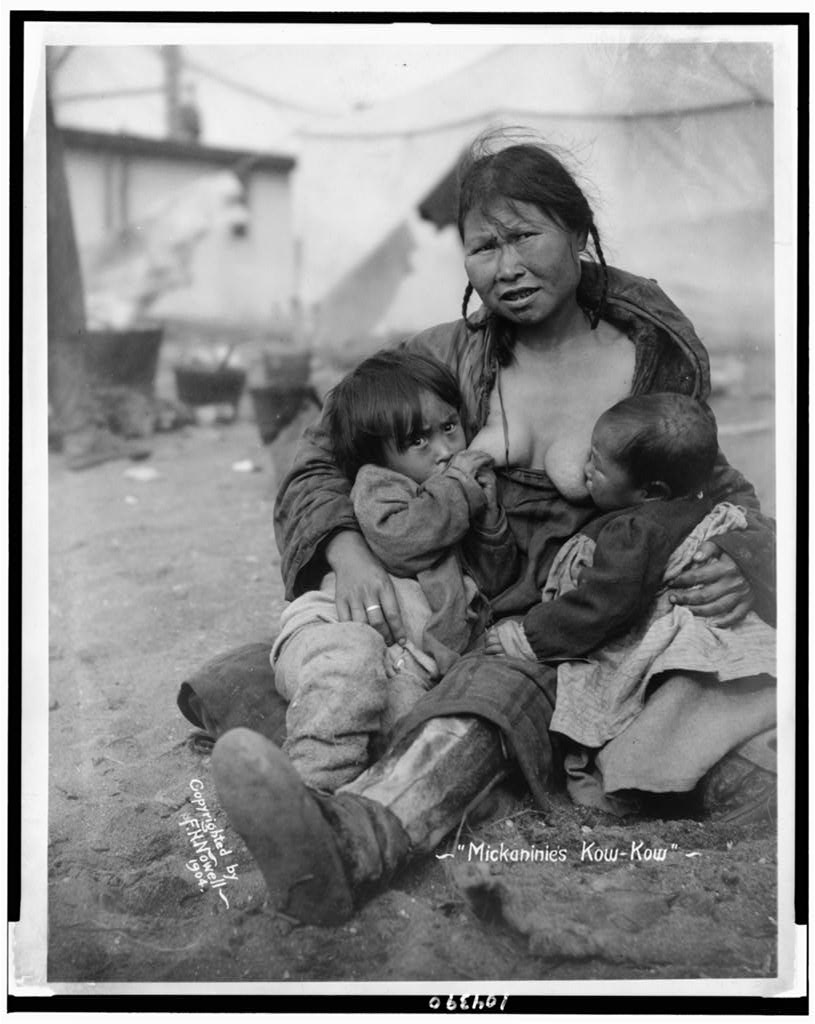

In order to fully encapsulate the significance of indigenous tattoo it is essential to first acknowledge that native histories did not begin with colonial settlement in North America. Additionally, Tattoo has had a wide spread of meaning for Indigenous women and it is impossible to minimize its importance to one locality or regional practice. Permanent adornment has been used for beautification, medicinal, religious, and ancestral purposes, all of which vary based on the individual cultures and heritage of each tribe and nation. For some, such as the Tlingit and Haida, tattoos signified social division within their societies and home units and were often depicted through animal crests “employed to affirm a group’s territorial claims”(Krutak 2007: 18). Thus, tattoo in this context served as a means of communal recognition outside of the context of colonial power, a principle which would later be utilized to implement a “resurgent politics of recognition” through reclamation (Coulthard 2014: 12). Other groups, such as the Yup’ik residents of Sivuqaq, utilized skin stitching and needle poking for both medicinal and social purposes (Adams 2018). Elder women within the community tattooed young women after they reached puberty by adorning them with chin lines believed to enhance their image (see Figure 1.). Similarly, it was not uncommon for Iglulingmiut residents of Iglulik to tattoo women’s thighs as it ensured that the first thing a newborn infant saw would be something of beauty (Gordon 1906: 81). Unangan peoples of Unalaska employed tattoos as a means of denoting the “accomplishments of their progenitors”, as they themselves became walking histories (Veniaminov 1840: 113). Practice in this sense was and continues to be incredibly varied amongst Indigenous populations and yet, regardless of the local, carries with it the identity and intent of the adorned.

Tattoo ritual itself also varied considerably from culture to culture and stands as an ever-evolving practice. For instance, many Alaska Native cultures utilized steel needle and threading techniques to imbed lampblack, a soot-based pigment into the skin around their chin, cheeks, forehead, and hands (Frobisher 1578: 61, 628). Others, such as the Hupa, Yurok, Karuk, and Shasta, groups local to the California region, employed flint and obsidian tools to scrape the skin and rub in soot sourced from the local sweathouses (Risling 17:10). Often, the experience served as a community-based event in which family members, particularly female members, would commune and carry out the ceremony for the recipient (Risling 16:17 ). Following European contact and subjection to assimilation, discrimination, and genocide at the hands of colonial powers, predominately the United States government, many specialized practices were eliminated from the historical record. Since then, remaining Indigenous tattooists such as Hovak Johnston (see Figure 2.) carried the additional role of transferring their knowledge bases to other communities whose customs were obscured by colonial erasure (Bommelyn 7:30). In some cases, tattoo practices underwent modification during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries as several Indigenous tattooists altered their practice to include steel needles and commercialized ink. In the face of widespread diaspora, such alterations allow for a more malleable means of establishing reclamation and revitalizing individual practice. The alteration of ritual should not be considered the establishment of ruin, rather, the acknowledgment of adaptation is crucial to recognizing the weight that tattoo practice carries in light of colonization.

Further, in an age in which women’s bodily autonomy is consistently the subject of discussion and debate, the implementation of state and federal legislature to control bodily modification, be it superficial or permanent, bears particular familiarity to American audiences. Rhetoric emphasizing codes of conduct for women emerged from the outset of colonial occupation with Puritan pamphlets such as A wonder of wonders, or, A metamorphosis of fair faces voluntarily transformed into foul visages or, an invective against black-spotted faces / by a well-willer to modest matrons and virgins… targeted facial adornment for young women (Miso-Spilus 1662). Taking this into account, within the United State’s territory, both state and federal governments have repeatedly attempted to establish legislature which both explicitly and subversively allows the state to control women’s and indigenous bodies. Until the implementation of The American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978, Indigenous ritual, ceremony, and practice was continuously targeted by state officials who manipulated the legislative ambiguity to contort the separation of church and state (Prucha 1984: 1127). Before then, states used the flexibility of the preexisting system to implement tattoo bans and other forms of adornment, such as the attempted implementation of Kansas’ 1915 law which “tried to make it illegal for a woman under the age of forty-four to employ cosmetics for the purposes of creating a false impression” (Davies 2020: 107) Nevertheless, state legislature continued to circumvent religious exemption through the outlaw of practice rather than adornment. Between 1963 to 2006, all practice of tattoo was outlawed within the state of Oklahoma, neither indigenous nor non-native persons within state territory could perform tattoo regardless of its religious significance (Baker 2004). This not only centralized the means of identification around “mediated forms of state recognition” but also reproduced colonial power through compliance in “accomodation” to state desire (Coulthard 2014: 10).

Not only has the United States government functioned as a colonizing entity that utilized its legislative framework to control Indigenous bodies, it has also implemented programs through which to contort Indigenous image. When utilized by colonial authorities, photographs have the capacity to “denaturalize their subject matter, and through the processes of enclosure, capture, and dissemination (e.g. cartes de viste and postcards) they symbolically gain power over their “subjects” by transforming them into “objects” that can be displayed, traded, or even destroyed” (Krutak 2007: 20-21). Just as legislation established a framework through which to authorize ruination of Indigenous practice, commissioned photography constructed the ruin’s image and publicized it, furthering the influence of colonial recognition. From this, it was not uncommon for government officials to carry out staged photography for the purposes of manipulating and controlling indigenous image as they propagandized the idea of native exoticism (Edwards 1992: 9). Through the proliferation of photographed propaganda not only did the United States delineate the means by which Native personhood was publicized, but through the extension of its legislative control, it regulated the means by which Indigenous persons could oppose them.

However, such measures are still in effect, albeit in different ways. With the present federal legislature currently in development to regulate social media platforms such as TikTok, the United States Congress has continued to attempt measures by which they can control indigenous means of expression (Masheshwari & Holpuch 2023). Despite this, creators have increased their media profiles exponentially over the past two decades and utilized accessible platforms to circumvent government intervention.

Presently, these women are actively engaged in “the production of culture perspective” as their development of modified traditional practice is continuously “conceived, created, distributed, evaluated, and utilized” in order to manifest recognition of identity Sanders & Vail 2008: 21). In a way, this movement is not dissimilar to the therapeutic usage of tattoos within institutionalized prison systems. Outlined in the research of Erving Goffman, individuals subject to continuous “identity stripping ” establish “kits” and symbolism through which that identity can be permanently reclaimed and withheld from officials (Goffman 1961: 14-21). For some, Indigenous ink served as “one of the last pieces’ ‘ left towards revitalization as adorning the body established a permanent visible construction of identity in the face of diaspora (Brommelyn 2:15). It is for this reason that reclamation answers the question of how, in the face of demoralization, objectification, and ruination we “recreate and recommunalize our worlds” (Escobar 2018: 200).

Likewise, bodily modification has also produced a means through which non-binary, transgender, and two-spirit persons have assumed identities contextualized by their ancestral heritage. Many native nations of the present day such as the Ojibwe nation contextualize gender under different criteria than other communities. On Kodiak Island in the early 19th century, those perceived by their community as women were “often brought up entirely in the manner of girl, and instructed in all the arts women use to please man: their beards are careful plucked as soon as they begin to appear, and their chins are tattooed like those of the women” (Langsdorff 1813: 47-48). As a result, for residents of Kodiak Island the body was not considered whole until its visage suited that of the individual’s communicated identity. Tattoo served as one of the most sacred mechanisms by which that fulfillment could be obtained and through adornment, individuals gained recognition within their communities. Presently, this practice is continued by two-spirit persons such as Yal (@good_suupaq), a Yup’ik content creator whose adornment of their tamlurun helped them reclaim their gender identity(@good_suupaq 2022).

Others utilize Indigenous adornment as a means of reconciliation and revival of their personal connections with their heritage and local communities. For Athabascan and Hän Gwich’in teacher’s assistant, Jaelynn Pitka (see Figure 3.), “they’re a symbol of strength, and a reminder of how hard our ancestors fought for us to be here” (Allaire 2022). In this instance, the acknowledgement of ruination is transformed into revitalization through the reclamation of traditional practice. It serves as a permanent reminder of Indigenous presence and connection and is a guiding path for others in the community to ground themselves. Hupa artist Lyn Risling viewed her “111” tattoo as an inspiration to other women in her community, guidelines which “reinforced [her] commitment to [her] culture” and allowed her “to build balance in [her] life” (see Figure 4.) (Rising 28:13). Rather than prescribe to colonial means of recognition, these women are actively shaping their own identities through ways of knowing that existed before European occupation. It is a conscious decision to engage with heritage and its significance. In a short form video Big Eagle reported: “What we are reviving is the understanding of their sacredness, their beauty, their power, and their cultural significance, by doing this we are making the path easier for our children to express themselves and to wear their culture with pride” (@stephaniebigeagle 2022). The significance of revitalization extends beyond the individual themselves, it is the active development of Indigenous means of recognition and serves as a locus for drawing upon centuries of native culture before and during colonial occupation.

However, while Indigenous tattoo serves as one of the most personal forms of recognition and reclamation, the subversive nature of Western colonial influence still presents considerable pushback towards native individuals. Dakota author Stephanie Big Eagle documents how “Western culture has distorted” facial tattoos “that tell our story, our identity, and our accomplishments, our commitments” and “twisted” their designation “into markings that instead make us unemployable, delinquents, less than, or unintelligent, or even less beautiful” (@stephaniebigeagle 2022). Additionally, Indigenous women are faced with individuals whose appropriation of native culture and practice has escalated with the popularity of tattoos as artistic expression. Through tattoo, the manifestation of cultural presence and history for Indigenous women is deeply ingrained into the body; they are “a way to celebrate a woman’s life, and when you dilute it and just anyone can get a traditional tattoo, those things aren’t celebrated and they aren’t important” (Adams 2018). Furthermore, the treatment of Indigenous image as a means of appropriative artistic expression is not only extended by the objectification of Native Americans, but also the perpetuation of colonial means of racism, discrimination, and idolization.The adornment of Indigenous iconography or portraiture often relies on caricatures and stereotypes and not only does not represent native history or existence in a respectful manner, but perpetrates those stereotypes to a public audience. In response to commentary defending non-indigenous adornment of Inuit and Ojibwe tattoo, social media activist Cheyanne @fireweedhoney declared that safeguarding native practices serves as the primary means by which indigenous communities “keep our people safe”, that it is “not only to make sure that nobody is a culture vulture but also to make sure that no one is going to hurt our people”(@fireweedhoney 2023). Conversely, many believe that widespread representation and visibility of tattoos serve as the most effective means of establishing recognition and education that will ultimately diminish appropriation. Lyn Risling, Hupa citizen and Yurok and Karuk descendant, defined the practice of appropriation as “uneducated” rather than filled with ill intent; “they’re uneducated to what this means to our people” “there is so much that has been appropriated from our culture” “I don’t want people to think, oh you just go into a tattoo shop and this is just what you decided to do because everybody is getting tattoos now” (Risling 25:00-28:00). Indigenous practice carries with it centuries of knowledge and cultural significance and is now a crucial tool for reclamation, adornment made without awareness bears the potential to ultimately undermine a vital means of revitalization for native individuals.

In light of established historiography, it is essential to further publicize how Native Women conceptualize their own histories through the means by which they are understood. Likewise, while there are connecting threads of Indigenous experience, native diaspora is a highly variable and personal experience that necessitates further investigation. Similarly, Native American tattoo is by no means the sole movement in which adornment is utilized for reclamation against colonial powers. Examples of other movements include Beber women of Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia, Sami of Scandinavia, Quechua of Peru, Ainu of Hokkaido, and Maori women of New Zealand. As the body is reterritorialized and centered as the locus for reclamation, permanent ink became a practice in which Indigenous women reassert their own forms of recognition against colonial regimes. An instrument supported by millennia, tattoo’s origins as an apparatus for “expressing, reinforcing, and camouflaging the psychological dimensions of life, love, health, illness, and death” is pivotal to many cultures around the world (Krutak 2007: 15). As colonial governments and institutions targeted bodily adornment for the purposes of cultural genocide and assimilation, Indigenous societies suffered from an erasure of their heritage and customs. Together, through the publicization of permanent ink, tattoos became a medium through which women in native communities are reconnecting with their own histories and using the medium to inspire others to revitalize and reclaim their own. Revitalization of Indigenous practice must be understood not only by its precolonial and colonial histories, but also by its modification and adaptation to suit native women in the present. Not only does tattoo establish “a more visible indigenous sisterhood”, it “helps erase the historical damage of betrayal and pain inflicted by others, because it is a form of permanent medicine.”(Adams 2018; Allaire 2022). All in all, the future of native reclamation is heralded by the likes of Lyn Risling, Stephanie Big Eagle, and Jaelynn Pitka, whose dedication and bravery is inked on their faces alongside thousands of like-minded women daring to rewrite their own narrative on their terms.

Works Cited

Adams, Ash. “An ‘Ancestral Memory’ Inscribed in Skin.” The New York Times, September 29, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/29/style/alaska-native-women-tattoos.html.

Allaire, Christian. “In Alaska, Indigenous Women Are Reclaiming Traditional Face Tattoos”. Vogue. March 8, 2022. https://www.vogue.com/article/in-alaska-indigenous-women-are-reclaiming-traditional-face-tattoos.

Baker, Michael “Tattooing: Banned in Oklahoma since 1963 Senate bill seeks to legalize, regulate businesses that practice in pinpricks.” The Oklahoman, February 9, 2004. https://www.oklahoman.com/story/news/2004/02/09/tattooing-banned-oklahoma-since-senate-seeks-legalize-regulate-businesses-that-practice-pinpricks/62003635007/.

Big Eagle, Stephanie (@stephaniebigeagle). 2022. “Part 6 @stephaniebigeagle #indigneoustattoo #indigenous #nativetiktok #LearnOnTikTok #culture #birthright #didyouknow.” TikTok, April 11, 2022.https://www.tiktok.com/@stephaniebigeagle/video/7085377546799320362.

Bommelyn, Lena, “Revitalization Stories: Lena Bommelyn.” California Indigenous Chin Tattooing. April 27, 2023, https://www.californiaindigenouschintattooing.com/.

Cheyanne (@fireweedhoney).2023. “Replying to @holistically_nicole kindly and holistically see yourself out #nativetiktok #native #nativetiktoks #indigenous #indigenoustiktok #indigenouspride #inuit #inuittiktok #alaskan #alaskannative #inuittattoo #inuittattoos #tuniit #tuniittattoos #closedpractice.” TikTok, March 31, 2023.https://www.tiktok.com/@fireweedhoney/video/7216810883664645418.

Coulthard, Glen. Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

Davies, Stephen. Adornment: What self-decoratioin tells us about who we are. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020.

Edwards, Elizabeth. “Introduction.” in Anthropology and Photography, 1860-1920. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992.

Escobar, Arturo. Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018.

Frobisher, Sir Martin. A true discourse of the late voyages of discovery for finding of a passage o cathaya and India by the North West. London: Henry Bynneman, 1578.

Goffman, Erving, ASYLUMS: ESSAYS ON THE SOCIAL SITUATION OF MENTAL PATIENTS AND OTHER INMATES. New york: Random House, 1961.

Gordon, George Byron. “Notes on the Western Eskimo.” in Transactions of the Department of Archaeology 2, no. 1 (1906): 101.

Krutak, Lars. The Tattooing Arts of Tribal Women. London: Bennet & Bloom/Desert Hearts, 2007.

Langsdorff, Georg H. von Voyages and Travels in Various Parts of the World During the Years 1803, 1804, 1805, 1806, and 1807.London : Printed for Henry Colburn, 1813.

Masheshwari, Sapna and Amanda Holpuch. “Why Countries Are Trying to Ban TikTok.” The New York Times, April 26, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/article/tiktok-ban.html.

Miso-Spilus., Smith, R., A wonder of wonders, or, A metamorphosis of fair faces voluntarily transformed into foul visages or, an invective against black-spotted faces. London: Printed by J.G. for Richard Royston, 1662.

Nowell, F. N. Mickaninies Kow-Kow. Photograph. Loc.gov, 1904. https://www.loc.gov/item/91794617/.

Parham, Vera. ““All Go to the Hop Fields” The Role of Migratory and Wage Labor in the Preservation of Indigenous Pacific Northwest Culture.” in Native Diasporas: Indigenous Identities and Settler Colonialism in the Americas. edited by Gregory D. Smithers, and Brooke N. Newman. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unc/detail.action?docID=1666553. 318.

Prucha, Francis Paul. Enumeration of areas of conflict from Francis Paul Prucha, The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians, volume 2. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984.

Reed, Jessica. “Tattoos, tanning and tears: inside the Yukon’s great indigenous festival” The Guardian, July 13, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2018/jul/13/canada-akada-festival-tattoos-inuit-first-nation

Risling, Lyn. “Revitalization Stories: Lyn Risling.” California Indigenous Chin Tattooing. April 27, 2023, https://www.californiaindigenouschintattooing.com/.

Risling, Lyn. “About Lyn Risling.” lynrisling.com. April 27, 2023. https://www.lynrisling.com/about-lyn-risling.html.

Sanders, Clinton R. and D. Angus Vail. Customizing the Body: The Art and Culture of Tattooing Revised and Expanded Edition. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2008.

Stoler, Anne Laura. Duress: Imperial Durabilities in Our Times. Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2016.

Veniaminov, Ivan Evsieevich Popov. Zapiski ob ostravakh Unalashkinskago otdiela [Notes on the Islands of the Unalaska District]. Translated by Richard Pierce. Kingston, Ontario: Limestone Press, 1984.

Yal (@good_suupaq). 2022. “I finally got my tamlurun! #nativetiktok #fyp #alaskanative #inuittiktok #yupik #nativetattoo #inuittattoo #nativewoman #twospirit.” TikTok, February 1, 2022 .https://www.tiktok.com/@good_suupaq/video/7059884410128174383.