By Kayla McManus-Viana

Introduction: “The Puerto Rican Problem”[1]

My capstone project is on the topic of Puerto Rican status alternatives and has largely been motivated by my own desire to find some hope for the future of Puerto Rico. But why does Puerto Rico need hope? Puerto Rico has been in an explicit colonial relationship with the United States (U.S) since 1898, when the island was ceded to the U.S. as part of the peace treaty that concluded the Spanish-American War. While some may argue that Puerto Rico achieved “decolonization” once it became a “Commonwealth” or “unincorporated territory” of the United States in 1952, I argue that the explicit colonial relationship between the U.S. and Puerto Rico has persisted, as the island’s shift in official legal designation to “Commonwealth” did nothing to tangibly address the technologies of colonial control the United States has and continues to implement to subjugate Puerto Rico.

“Technologies of colonialism” are the explicit mechanisms of domination that are used by colonial powers to subjugate and dispossess colonial subjects. These mechanisms can manifest politically, economically, strategically (i.e. be related to military concerns), culturally, etc. While I will be unable to get into the nitty-gritty of each and every technology of colonial subjugation the United States employs to keep Puerto Rico subordinate and dependent, I will address a few of the most explicit here.

The first technology of colonial control operating in Puerto Rico is constitutional, and subsequently political, domination. While Puerto Rico does have its own constitution and Puerto Ricans “…[can] elect their own local government, governor, and legislature,” Puerto Ricans remain “subject to Congress’s power under the Territorial Clause of the US Constitution and previous Supreme Court rulings [specifically the Insular Cases],” among other political limitations.[2] In other words, “Congress gives and Congress takes,” as the rulings of the U.S. federal legislature, in every scenario, supersede those of the Puerto Rican legislature. Additionally, the precedent set by the Insular Cases, which are a series of early-twentieth century Supreme Court rulings that established the “separate and unequal” status of U.S. territories, has created a situation in which only the barest of rights are guaranteed to Puerto Ricans as U.S. citizens.[3] Anything beyond the “fundamental rights established in the Constitution” are prejudicially and inconsistently decided upon on a case-by-case basis by the U.S. Supreme Court.[4] For example, the right to vote in federal elections is not one of the “fundamental rights” conferred to Puerto Ricans, and Puerto Ricans’ access to various social welfare programs (such as Supplemental Security Income) is decided by the Supreme Court and not guaranteed to Puerto Ricans by virtue of possessing American citizenship alone. Thus, not only do Puerto Ricans have functionally little control over their island’s governance, they also inhabit a space of second-class U.S. citizenship.

In order to fully understand the concept of “second-class citizenship,” one must first understand what full modern citizenship entails. According to Ariana Valle, “At its simplest level, citizenship is a legal status that represents formal membership in a political community; as such, citizenship as status distinguishes between citizens and foreigners” (emphasis added).[5] Beyond this legal differentiation, citizenship also confers “social, civil, and political rights as well as duties and responsibilities to all citizens” and, even further, a sense of belonging to a larger national community (emphasis added).[6] Valle argues that Puerto Ricans lack both the legal and social conceptions of membership modern citizenship confers. For Puerto Ricans, the lack of citizenship’s legal protections manifests in ways previously mentioned (not being able to vote in federal elections, unequal funding for and access to federal welfare programs), and the lack of a social membership conferred through citizenship – of belonging to the American national imaginary – manifests through the racialization of Puerto Ricans as “Latino.” According to Valle, Puerto Ricans are “subsumed into the Latino group and the broader racialization of Latino with foreigner” and as such are perpetually viewed as “Other than” American.[7] This results in a lack of inclusion of Puerto Ricans in the American imaginary. Moreover, Valle argues that the racialization of and discrimination against Puerto Ricans have been further compounded by socioeconomic vulnerability stemming from decades of colonial economic exploitation and dependence, which has contributed to the conceptualization of Puerto Ricans as “lazy, welfare dependent, and criminal.”[8]

The colonial technology of economic domination and exploitation manifests in Puerto Rico as colonial-capitalism. Colonial-capitalism refers to the “mutually constitutive and inextricable links that exist amongst capitalist logics and colonial power, which can continue even after formal colonization ends. These indissoluble relationships…continue to be highly influential in how governance, societies, economies, and certain cultural norms have been fashioned and operate [in the Caribbean and other formerly colonized territories].”[9] In other words, the technology of capitalism acts as an extension of and complement to colonial power, as capitalist policies are enacted through and inseparable from “colonial worldviews, institutions, and relations.”[10]

As Naomi Klein evidences in The Battle for Paradise: Puerto Rico Takes on the Disaster Capitalists, colonial-capitalism is a persisting economic paradigm and tangible reality in Puerto Rico. Colonial-capitalism is so prevalent on the island that Klein goes so far as to describe the Puerto Rican experience as “shock-after-shock-after-shock doctrine.”[11] This “cyclical invasion and retreat of [American] colonial capital” is intimately tied to the imposition of neoliberal policies by the United States, which have wrecked the island’s manufacturing, education, and public sectors, resulting in “capital flight and the erosion of social programs and economic opportunities.”[12] This in turn creates additional crises, such as “unemployment, crime, debt, [and] dilapidated infrastructure,” which are used to further justify even more “austerity and privatization…exacerbating existing crises, spawning new ones, and continuing the cycle” of colonial capitalism and dependence.[13] A timely example to root the idea of colonial-capitalism in the reality of life on the island is the current move to privatize Puerto Rico’s power grid. As of January 25, 2023, Genera PR, a subsidiary of the New-York based company New Fortress, Inc., has signed a ten-year contract to take charge of operating and maintaining the island’s outdated and failing power grid from the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA), the public corporation previously in charge of the power grid until its 2017 bankruptcy.[14] While this is but a singular example of colonial-capitalism in Puerto Rico, it is part of a larger history of capitalist exploitation that has resulted in a ballooning $73 billion debt crisis, a massive flight of Puerto Ricans from the island, and immense economic inequality.

In addition to accelerating neoliberalism and austerity measures on the island, colonial-capitalism is directly working to dispossess Puerto Ricans of their homes and land. First established in 2012 to attract outside investment in exchange for income tax breaks, Act 60 of the Puerto Rican tax code grants massive tax breaks to Americans who relocate to Puerto Rico and establish a “bona fide” residence on the island. Since its inception, Act 60 has expanded its purview to “attract finance, tech and other investors” (such as “crypto currency miners”) in addition to new residents.[15] While resulting in an influx of cash to and interest in the island, the growth of the wealthy (largely white) American population has increased property prices on the island, accelerated gentrification, and resulted in the internal displacement of native Puerto Ricans.

Additionally, the explicit political and economic colonial modes of domination discussed above have led to the development of a state of “coloniality” in Puerto Rico. “Coloniality,” an idea pioneered by Anibal Quijano and further developed by Puerto Rican philosopher Nelson Maldonado-Torres, is defined as “long-standing patterns of power that emerged as a result of colonialism…that define culture, labor, intersubjective relations, and knowledge production well beyond the strict limits of colonial administrations” (emphasis added). According to Irma Serrano-García, the explicit modes of colonial relation and domination discussed above have led to and perpetuate a state of coloniality in Puerto Rico; colonialism and coloniality thus occur simultaneously, though they manifest in different ways. Serrano-García argues that coloniality in Puerto Rico primarily emerges in “the ‘Americanization’ of our way of life and the psychological, as well as concrete, dependence on U.S. welfare…[which have] generated a sense of American superiority, the idea that the United States is a nation to emulate, and that were it not for the United States we could not survive”[16]

The concept of coloniality and internalized inferiority is unpacked further in Chapter 2 of my thesis, but for now it is important to note that Puerto Rico exists in both a colonial relationship with the United States and a state of suspended coloniality. Thus any decolonization plan that does not sufficiently address both of these aspects of American domination will simply result in a reification of Puerto Rico’s subordinate, colonial status in relation to the United States.

Solving the “Puerto Rican Problem”

The most recent attempt to remedy the colonial relationship between the U.S. and Puerto Rico is the Puerto Rico Status Act (PRSA), introduced in the United States House of Representatives on July 20, 2022. Should the PRSA pass both the U.S. House and Senate, it would call for a binding plebiscite to decide Puerto Rico’s future. The current options between which Puerto Ricans would vote include: 1) full admission into the American Union as the 51st state, 2) independence in a Westphalian sense, or 3) a “Free Association” between a sovereign Puerto Rico and the United States.

Far from uniting the Puerto Rican people, however, the PRSA has been a source of controversy and debate. The grassroots social justice and decolonization advocacy organizations Boricuas Unidas en la Diaspora and CASA condemned the bill as being “negotiated behind closed doors in Washington, D.C., with minimal input from the Puerto Rican people.”[17] Other organizations, such as LatinoJustice and Power4PuertoRico, have similarly come out against the legislation in its current form because they claim it “[ignores] our community’s drumbeat for transparency and fairness.”[18] This sentiment was further echoed by Representative Jesús “Chuy” Garcia, a democrat from Illinois who currently sits on the House Natural Resources Committee, who justified his vote against the bill by arguing that “[the Puerto Rican community] was not given an opportunity to contribute their perspectives into the debate.”[19] The critiques presented here raise an important, albeit ironic, question: if the Puerto Rican people had little say in the plan meant to give them a voice in their island’s decolonization process, then whose opinions or voice does the bill actually reflect?

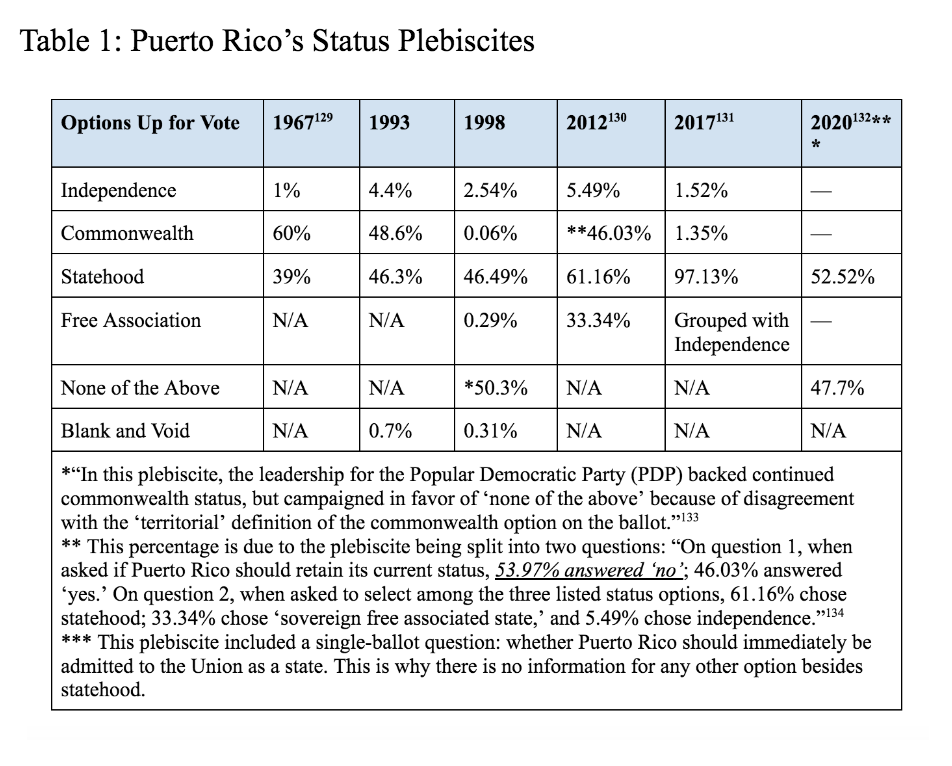

The lack of Puerto Rican input in the PRSA suggests that the bill centers the interests and positionality of the colonizer (the United States) more than it presents any true decolonial option for the colonized (Puerto Rico). This is not a novel argument, however. Puerto Rico’s decolonization process has been dominated by U.S. interests from the start, as evidenced by the factthat the same pool of options have been presented to the Puerto Rican people in seven separate plebiscites since 1967 (See Table 1). The only difference between the PRSA and these earlier plebiscites is that the option of the Commonwealth, or the ability to maintain the current status quo, would not be up for vote. The fact that Puerto Ricans have been presented with and have voted upon the same three options for decades speaks not only to the lack of interest or effort on the part of the United States to truly solve the “Puerto Rican Problem,” but also highlights how limiting these options truly are. Moreover, the PRSA’s attempt to “move the meter” towards a solution by presenting, once again, the same three options has only re-enforced the status stalemate. This begs the question: if these three options do not seem to be moving Puerto Rico toward decolonization, what other path(s) exists for the island?[20]

My research addresses this question by imagining an alternative path forward to shake up Puerto Rico’s status stalemate. Importantly, my research focuses on generating possibilities by thinking-through a different or “fourth” status option that could grant Puerto Rico dignified decolonial justice – not evaluating its viability or operationalizability. In this paper, “decolonial justice” is conceptualized as a status for Puerto Rico that directly addresses and remedies the colonial power relations between the island and the United States (i.e. the “colonial rot,” which includes the concept of coloniality), and prevents future (neo)colonial subordination from developing.

Methodological Approach: Hopeful Pessimism

“We have to find something that works for us. We have to create something new. And I think that’s where we are headed. There is a new movement that is being forged here. It still hasn’t been born, but it’s about to be born. A new future for Puerto Rico is already developing.” “Annie”[21]

As Yarimar Bonilla notes in “Postdisaster Futures: Hopeful Pessimism, Imperial Ruination, and La futura cuir,” in addition to a plethora of political, environmental, and economic crises, Puerto Ricans are currently experiencing the aftereffects of a “postcolonial disaster,” or “a political context of material and affective ruin that isno longer guided by the promise of a better postcolonial future or the palliative anticipation of a sovereignty to come” (emphasis added).[22] This means that many Puerto Ricans have become disillusioned with the promise of a future in line with the current, hegemonic definition of political “modernity” – understood here primarily by its organizing political factors, Westphalian-based sovereignty and territorially-bound states.[23] Thus, the question of “what comes next?” for many on the island no longer involves dreams of political independence or even US statehood, as successive mismanaged crises have shattered their faith in government. As one man Bonilla interviewed remarked, “The government [both local and federal] doesn’t work. So now we have to work harder because the government can no longer help us.”[24]

According to Bonilla, the pervasive feeling on the island is that top-down, government reform is not the solution; the Puerto Rican people are. Thus, self-reliance and community care, i.e. grassroots or bottom-up movements, not another status plebiscite, are increasingly seen as the most likely way to break free of US dependence.[25] This sentiment stands in stark contrast to the Puerto Rican Status Act and reaffirms the critique that those composing the bill did not take into account the perspectives and opinions of the Puerto Rican people but instead re-packaged and re-imposed what they thought the Puerto Rican people should want.

Bonilla takes care to assert that this turn toward community solutions is not an act of “giving up” but rather one of “hopeful pessimism.”[26] She asks, “Unlike a cruel optimism that blind us to the threats of the present, a hopeful pessimism opens our eyes to the hard tasks required to transform the here and now. How can we live and act politically in the absence of faith in a better future?[27] How can we develop not a cruel optimism that blinds us to what is to come but rather a kind of hopeful pessimism that can serve to build politically in the face of ruin and the promise of further decay?”[28] These are questions central to Bonilla’s current work and ones that have motivated my own research. To this end, I aim to build upon Bonilla’s work and critique what has been historically presented by the United States as the only potential paths forward for Puerto Rico and infuse the discursive conversation surrounding the “Puerto Rican Problem” with a sense of possibility in line with Bonilla’s call for “hopeful pessimism.”

While I amconscious ofthe disenchantment with both the U.S. and Puerto Rican governments across the island, I contend that top-down government transformations are possible and indeed necessary for Puerto Rico to decolonize because without such structural transformation, the rot of colonialism remains.[29] Thus, I am preoccupied in this thesis with exploring what alternative top-down government transformations are possible for Puerto Rico when inspired by and rooted in the grassroots organizations and solidarities the Puerto Rican people themselves view as the best path forward.[30]

In order to incorporate the voices of Puerto Ricans themselves, in lieu of being able to speak with them directly via ethnographic research, I analyze the work of three grassroots organizations on the island in order to imagine an alternative future rooted in the work of Puerto Ricans themselves. For the purpose of this short paper, I will only include my analysis of one: El Departamento de la Comida.

Imagining an Alternative: Grassroots Innovation and El Departamento de la Comida

“Prefigurative politics” is the main analytical framework through which I analyze the work of grassroots organizations across the island. As understood by Paul Raekstad, the “case” for prefigurative politics: “…starts from the premise that our basic institutions – capitalism, the state, the patriarchal family and so on – are inherently unfree and unequal…how can we emancipate ourselves if current institutions prevent us from developing the powers, drives and consciousness we need to do so?…Organizations of struggle and transition must begin to implement the social relations and practices they want for the future in the here and now. This is because doing so is important for developing the right kinds of revolutionary agency; for developing the powers, drives and consciousness necessary to bring about universal human emancipation” (emphasis added) (37-38).[31] In other words, prefigurative politics is concerned with living out a desired future in the present, with bringing into being by doing.

Prefigurative politics is closely related to what Puerto Rican filmmaker, scholar, and activist Frances Negrón-Mutaner describes as “sovereign acts.” Sovereign acts are understood as the “freedom to act and imagine in excess of an imposed law, order, or norm, [and may be] capable of opening up other ways of being in the world…In this context, sovereignty can be understood as the capacity to act and be otherwise” (emphasis added).[32] Sovereign acts attack both colonialism – through the actions themselves – as well as coloniality, through the concept of “problematization.” According to Cristina Pérez Jiménez, problematizacion subverts coloniality through the critical analysis of peoples’ “submission and exploitation” which leads to the realization that said submission is not natural and instead “the result of alterable socio-historical processes” (emphasis added).[33] It is this combination of action and analysis found in sovereign acts that “should lead to a different understanding of reality, and the belief that people can alter their circumstances.”[34]

Each organization discussed in my project involves both an action that directly works to undermine the ongoing relations and effects of colonialism in Puerto Rico as well as an effort to problematize Puerto Ricans’ exploitation and subjugation, thus targeting the island’s state of coloniality. Therefore, each organization is engaging in sovereign acts. Additionally, the work of these organizations is prefigurative in the sense that they are working toward a Puerto Rico in the present that they want to see emerge in the future. Thus, the following organizations can be described as engaging in prefigurative sovereign acts.

El Departamento de la Comida: Food Sovereignty

As mentioned earlier, part of the status quo in Puerto Rico is colonial subjugation by and dependence on the United States. Economic dependence in particular – on PROMESA to restructure the island’s billion-dollar debt crisis, on an infusion of cash from American investors and corporations – is part and parcel to everyday life on the island. This dependency can be starkly seen in the agricultural and food sectors.

Between 80-90% of the total food supply in Puerto Rico is imported, which has resulted in intense levels of dependency – particularly on imports from the United States:[35] “There is local agricultural production, but the food distribution companies have an almost absolute control of the market. While it is not hard for producers to grow food, it is quite hard for them to sell it. Local produce is frequently more expensive than imported food, even with taxes and transportation costs added. Since most of the Puerto Rican economy turned to developing its industrial sector decades ago, there is very little economic incentive from the government to boost local agricultural production and make it more competitive” (emphasis added).[36]

In the face of this extreme dependency, food sovereignty organizations are popping up across the island. Food sovereignty is as much about “having enough food” as it is creating “place-based alternatives to the destructive logic of the colonial state and highlight[ing] the imaginative potential of thinking beyond what exists…food sovereignty cultivates healing through mutual aid and community care, connecting resistant imaginations to tangible political possibilities” (emphasis added). El Departamento de la Comida is one of the most public-facing and well-known organizations trying to bring about food sovereignty in Puerto Rico.

El Departamento de la Comida (El Depa) was founded in 2010 by Tara Rodríguez-Besosa as a multi-farm community agriculture program that “aggregated produce from farms and sold it to families and restaurants in San Juan.”[37] Since then, the work of El Depa has expanded to encompass a food hub, a restaurant, and in the face of Hurricane Maria’s destruction, support for coalitions of volunteer brigades to help local farms in the aftermath of the disaster.[38] Through these initiatives, El Depa not only works to actively undermine the dependent and colonial relationship between Puerto Rican and the United States by providing access to locally grown (i.e. non-imported) food, but also the coloniality this relationship engenders.[39] As Rodríguez-Besosa notes, “We were told how to be civilized: It’s the can, it’s the microwave, it’s going into the supermarket and having money to treat yourself to packaged foods…we were told that these fruit trees growing in our backyards were worthless,” but El Depa problematizes this narrative and successfully illustrates that Puerto Ricans can support themselves, that the island provides, and that reliance on the United States and its packaged foods is not necessary.[40]

A common phrase among food sovereignty activists is, “if you can feed yourself, you can free yourself.”[41] In the case of Puerto Rico, El Depa is working to free Puerto Ricans from having to engage with a highly exploitative capitalist food system that is a byproduct of a dependent colonial relationship with the United States.[42] Thus, El Depa is engaging in prefigurative work to bring about a self-sustaining, “free” Puerto Rico.

What Are Puerto Ricans Showing Us They Want?

Using the concepts of prefigurative politics and sovereign acts, my analysis of grassroots mobilization in Puerto Rico points toward the following answer to the above question: self-sufficiency, an end to structural harms created and perpetuated by colonialism, and engagement in acts of consciousness raising that help to actively challenge coloniality and internalized inferiority.

I argue that a top-down “fourth-option” for Puerto Rican decolonization should be focused on generating an alternate “relationship with government.”[43] This top-down plan would involve re-orienting the Puerto Rican government to a supportive position focused on creating the infrastructure, policy, resource coordination, etc. necessary to support the expansion and existence of prefigurative organizations – across the island and even the world – and the sovereign acts they engage in.Such a “fourth option,” inspired by and rooted in supporting the mobilization and solidarity of Puerto Ricans, would not only help break the cycle of colonial dependency and foster self-sufficiency throughout the island, but also challenge the structural harms brought about due to both Puerto Rico’s colonial relationship with the U.S. and state of coloniality. Such a plan would allow Puerto Ricans to slowly untangle the threads that tether them to the United States and provide the decolonial future Puerto Ricans deserve – on their own terms.

The Bully in the Backyard: Issues for Operationalizing Puerto Rican Decolonization

The seeds of a decolonial future have already been planted in Puerto Rico, as evidenced by the prefigurative sovereign actions explored further in Chapter 3 of my thesis, and as such it is relatively easy to answer the question: what else is out there for Puerto Rico beyond the traditional three status options? But even beyond that, Puerto Ricans are showing us that the answer to this question — fostering the creation, existence, and spread of radical grassroots movements across the island – is possible to implement. But how does one create a top-down decolonization plan that fosters, for example, radical anti-capitalist food sovereignty projects? More specifically, what functional barriers exist to creating and implementing such a top-down decolonization plan throughout the island?

Before moving forward, it is imperative to state that this conclusion does not claim that a de-colonization plan along the lines of what has been imagined is unfeasible. Rather, it is here that I am engaging most directly with the pessimistic aspect of “hopeful pessimism.” Thus, in this section I am identifying what I believe to be the major challenges facing the arrival of any imagined decolonial future in Puerto Rico. Moreover, I argue that instead of debating whether or not a free association, the achievement of American statehood, or Westphalian independence is “right” for Puerto Rico for another sixty years, future researchers, policymakers, and those invested in Puerto Rico’s decolonial future should be more concerned with the following issues.

Firstly, as it stands, due to the island’s official Commonwealth status, both the U.S. House and the Senate would need to vote upon a decolonization plan in order for it to be implemented in the first place but also for Puerto Rican decolonization to be considered “legitimate” and “legal” – both in the eyes of the United States and the wider global community.[44] That being said, the United States has a rather violent knee-jerk reaction to anything “Other” in what it sees as its “backyard,” i.e. the entire Western hemisphere (see the Grenadine Revolution, the US’s involvement in Cuba and throughout Central and South America during the twentieth century for more information). Using the example I presented earlier, food sovereignty movements are inherently anti-capitalist, and addressing the structural harms incurred from unchecked and predatory colonial capitalism would be an inherently anti-capitalist project and thus considered unacceptable by the United Status. Resultantly, any plan that seems to challenge or undermine capitalism in any way would probably not pass Congress.[45] The question to ask ourselves now is: how do we get a decolonial plan with anti-capitalist components through Congress?

Second, there exists ample evidence of the predatory nature of neoliberal international institutions, such as the IMF and the World Bank, in their interaction with “developing” or recently-independent countries (see the documentary Life and Debt for more information). Resultantly, an important question is: how do we navigate the constraints of (transnational, exploitative) capitalism and protect Puerto Rico from incursions by global neoliberal institutions? Even further, what role, if any, does regional integration play in protecting Puerto Rico against neoliberalism and further economic exploitation?

Third, as Frantz Fanon argued in The Wretched of the Earth, having the colonial bourgeois (who are “mimic men” that want to assimilate with the colonists) come to power after a colonizer retreat results in “neo-colonialism.” With that in mind, how do we guard against elite-capture and potentially the establishment of neo-colonial relations with the United States? (This is a major concern for Puerto Rico, given the history of former U.S. colonies’ postcolonial experiences, see: The Philippines).[46]

Finally, the “national question” is still an unanswered and incredibly complicated question in Puerto Rico. A de-colonization plan rooted in island-wide and international networks and solidarities would help challenge the idea that national space and a state’s territory are congruent, thus making more “space” for the diaspora in the “Puerto Rican imaginary.” However, the issue of who is and is not Puerto Rican is about much more than geographic location – it is about language, race and ethnic background (ex. if you are part of the Creole elite or of African or Taíno-descent), where you were educated, etc. Additionally, there exists a “hierarchy of suffering” in determining if one is “Puerto Rican enough.” Meaning, the more time you have spent on the island, enduring the effects of colonization, climate change, the debt crisis, etc., you are “more” Puerto Rican than those who were born and raised in the diaspora and insulated from such experiences and subsequent suffering. Working through these issues, in my opinion, is as difficult as getting an anti-capitalist decolonization plan through the U.S. Congress, because it would require a problematization of the diaspora among Puerto Ricans – both on the island and off – and the challenging of a generations-long understanding of what it means to be Puerto Rican.

The obstacles identified in this section are some – not all – of what I believe to be the most pressing challenges facing the implementation of any decolonial plan in Puerto Rico today.[47] While daunting, addressing these questions, in lieu of debating the efficacy of the three traditional status options for another sixty years, will result in more productive conversations regarding the “Puerto Rican problem” and generate the type of critical, problematizing engagement necessary for creating a true, dignified decolonial future for the island.

Bibliography

Acevedo, Nicole. “Puerto Rico Officially Privatizes Power Generation Amid Protests, Doubts.” NBC News, January 25, 2023. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/puerto-rico-officially-privatizes-power-generation-genera-pr-rcna67284.

Bonilla, Yarimar. “The coloniality of disaster: Race, empire, and the temporal logics of emergency in Puerto Rico, USA.” Political Geography 78 (2020): 1-12.

Bonilla, Yarimar. “Postdisaster Futures: Hopeful Pessimism, Imperial Ruination, and La futura cuir,” small axe 62 (2020): 147-162.

“BUDPR, CASA Issue Joint Statement on Opposition to Puerto Rico Status Act.” Latino Rebels, August 19, 2022. https://www.latinorebels.com/2022/08/19/bupdrpuertoricostatusact/.

Bustos, Camila. “The Third Space of Puerto Rican Sovereignty: Re-imagining Self-Determination Beyond State Sovereignty.” Yale Journal of Law and Feminism 32, no. 1 (2020): 73-102.

Cabán, Pedro. “Bad Bunny, AOC, and Decolonizing Puerto Rico.” The American Prospect, September 7, 2022. https://prospect.org/politics/bad-bunny-aoc-and-decolonizing-puerto-rico/.

Coulthard, Glen. Red Skin, White Masks. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove Press, 1963.

Gahman, Levi, Gabrielle Thongs, and Adaeze Greenidge. “Disaster, Debt, and Underdevelopment: The Cunning of Colonial Capitalism in the Caribbean.” Development 64 (2021): 112-118.

Kirts, Leah. “How El Departamento de la Comida Fights Colonialism Through Food,” them, October 21, 2022. https://www.them.us/story/el-departamento-de-la-comida-tara-rodriguez-besosa-puerto-rico-food-farming.

Life and Debt. Directed by Stephanie Black. Los Angeles: Tuff Gong Pictures Production, 2001.

Mignolo, Walter. “Epistemic Disobedience and the Decolonial Option: A Manifesto.” Transmodernity: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World 1, no. 2 (Fall 2011): 44-66.

Murphy Marcos, Coral and Patricia Mazzei. “The Rush for a Slice of Paradise in Puerto Rico.” The New York Times, January 31, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/31/us/puerto-rico-gentrification.html.

Raekstad, Paul. “Prefiguration: Between Anarchism and Marxism,” In The Future is Now: An Introduction to Prefigurative Politics, edited by Lara Moticelli, 32-46. Bristol: Bristol University Press, 2022.

Rodrigues, Meghie.“Puerto Rico Adapts to a Changing, Challenging Environment.” UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, April 22, 2021. https://eos.org/articles/puerto-rico-adapts-to-a-changing-challenging-environment.

Rodriguez, Franklin, and Richard Huizer. “The Politics of Inclusion and Exclusion: Puerto Rico, Colonialism, and Citizenship,” Middle Atlantic Review of Latin American Studies 3, no. 2 (2019): 119-140.

Serrano-García, Irma. “Resilience, Coloniality, and Sovereign Acts: The Role of Community Activism.” American Journal of Community Psychology 65, no. 3 (2020): 3-12.

Standen, Alex. “Confronting Colonial Capitalism.” Review of The Battle for Paradise: The Battle for Paradise: Puerto Rico Takes on the Disaster Capitalists, by Naomi Klein. New Labor Forum 29, no. 1 (Winter 2020). https://newlaborforum.cuny.edu/2020/02/01/confronting-colonial-capitalism/.

Stoler, Ann Laura. Duress: Imperial Durabilities in Our Times. Durham: Duke University Press, 2016.

Stoler, Ann Laura. “‘The Rot Remains:’ From Ruins to Ruination.” In Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination, edited by Ann Laura Stoler. Durham: Duke University Press, 2013.

Valle, Ariana. “Race and the Empire-state: Puerto Ricans’ Unequal U.S. Citizenship.” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 5, no. 1 (2019): 26–40.

Wilms-Crowe, Momo. “‘Desde de Abajo, Como Semilla:’ Puerto Rican Food Sovereignty as Embodied Decolonial Resistance.” B.A. Honors Thesis, University of Oregon, 2020.

[1] “The Puerto Rican Problem” is a colloquial phrase used to refer to Puerto Rico’s “in-between” status as neither a U.S. state nor a Westphalisn (nation) state. Rather, Puerto Rico is an “unincorporated territory” of the United States, but what this means, entails, and what rights this status secures for the Puerto Rican people in practice is constantly up to (re)interpretation. Solving the Puerto Rican Problem would involve providing clarity re: the island’s status.

[2] Franklin Rodriguez and Richard Huizer, “The Politics of Inclusion and Exclusion: Puerto Rico, Colonialism, and Citizenship,” Middle Atlantic Review of Latin American Studies 3, no. 2 (2019): 135; “Article IV, Section 3, Clause 2 of the United States Constitution, the ‘Territorial Clause,’ empowers Congress to ‘make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States’” (emphasis added) (Rodriguez and Huizer 130).

[3] Puerto Ricans were granted U.S. citizenship in 1917 as part of The Jones Act, but as many authors argue (Torruella 2017, Smith 2017), Puerto Ricans experience second-class and incomplete U.S. citizenship.

[4] Rodriguez and Huizer, “The Politics of Inclusion and Exclusion,” 131.

[5] Ariana Valle, “Race and the Empire-state: Puerto Ricans’ Unequal U.S. Citizenship,” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 5, no. 1 (2019): 27.

[6] Valle, “Race and the Empire-state,” 27.

[7] Ibid., 36.

[8] Ibid., 27.

[9] Levi Gahman, Gabrielle Thongs, and Adaeze Greenidge, “Disaster, Debt, and Underdevelopment: The Cunning of Colonial Capitalism in the Caribbean,” Development 64 (2021): 113.

[10] Gahman, Thongs, and Greenidge, “Disaster, Debt, and Underdevelopment,” 114.

[11] Here, Klein is making an explicit reference to her breakthrough and widely praised book, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism.

[12] Alex Standen, “Confronting Colonial Capitalism,” review of The Battle for Paradise: The Battle for Paradise: Puerto Rico Takes on the Disaster Capitalists, by Naomi Klein, New Labor Forum 29, no. 1(Winter 2020): https://newlaborforum.cuny.edu/2020/02/01/confronting-colonial-capitalism/.

[13] Standen, “Confronting Colonial Capitalism,” https://newlaborforum.cuny.edu/2020/02/01/confronting-colonial-capitalism/.

[14] Nicole Acevedo, “Puerto Rico Officially Privatizes Power Generation Amid Protests, Doubts,” NBC News, Jan. 25, 2023. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/puerto-rico-officially-privatizes-power-generation-genera-pr-rcna67284.

[15] Coral Murphy Marcos and Patricia Mazzei, “The Rush for a Slice of Paradise in Puerto Rico,” The New York Times, January 31, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/31/us/puerto-rico-gentrification.html.

[16] Irma Serrano-García, “Resilience, Coloniality, and Sovereign Acts: The Role of Community Activism,” American Journal of Community Psychology 65, no. 3 (2020): 4.

[17] “BUDPR, CASA Issue Joint Statement on Opposition to Puerto Rico Status Act,” Latino Rebels, August 19, 2022, https://www.latinorebels.com/2022/08/19/bupdrpuertoricostatusact/.

[18] Pedro Cabán, “Bad Bunny, AOC, and Decolonizing Puerto Rico,” The American Prospect, September 7, 2022, https://prospect.org/politics/bad-bunny-aoc-and-decolonizing-puerto-rico/.

[19] Pedro Cabán, “Bad Bunny, AOC, and Decolonizing Puerto Rico,” https://prospect.org/politics/bad-bunny-aoc-and-decolonizing-puerto-rico/.

[20] Through a qualitative analysis of de-colonial critiques of Eurocentric modernity, Chapter 2 of my thesis goes into more depth as to why the “traditional status options” would not bring about decolonial justice for Puerto Rico. This discussion has been excluded for the purpose of this short paper.

[21] Yarimar Bonilla, “The coloniality of disaster: Race, empire, and the temporal logics of emergency in Puerto Rico, USA,” Political Geography 78 (2020): 10.

[22] Yarimar Bonilla, “Postdisaster Futures: Hopeful Pessimism, Imperial Ruination, and La futura cuir,” small axe 62 (2020): 150.

[23] Aka “statist solutions.”

[24] Yarimar Bonilla, “The coloniality of disaster…” 7.

[25] Bonilla, “The coloniality of disaster…,” 9.

[26] Also referred to in this thesis as “visionary pragmatism.”

[27] Here, Dr. Bonilla is referring to Lauren Berlant’s book Cruel Optimism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012) here.

[28] Bonilla, “Postdisaster Futures: Hopeful Pessimism, Imperial Ruination, and La futura cuir,” 157.

[29] I also recognize that this is a rather privileged position to take, keeping in mind my positionality as a member of the Puerto Rican diaspora who was born, raised, and educated on the mainland;

This is a direct reference to Ann Laura Stoler’s “‘The Rot Remains:’ From Ruins to Ruination,” In Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination, ed. Ann Laura Stoler. Durham: Duke University Press, 2013.

[30] That being said, I do recognize the need to imagine within the confines of reality, to be rationally “hopefully pessimistic”. As Frank Gatell observed when discussing the state of the Puerto Rican status debate in the 1940s, “…without a viable economic life, arguments about political status represented a luxury which the island simply could not afford” (emphasis added).# This remains the case today, nearly eighty years later. With this in mind, while the majority of this thesis imagines an ideological ground upon which we can build a fourth option by listening to the opinions and analyzing the actions of the Puerto Rican people, the conclusion brings us back down to Earth and investigate the tangible barriers impeding the development of said imagined future in Puerto Rico today.

[31] Paul Raekstad,“Prefiguration: Between Anarchism and Marxism,” In The Future is Now: An

Introduction to Prefigurative Politics, ed. Lara Moticelli (Bristol: Bristol University Press, 2022): 37-38.

[32] Irma Serrano-García, “Resilience, Coloniality, and Sovereign Acts: The Role of Community Activism,” The American Journal of Community Psychology 65, no. 3 (2020): 7.

[33] Irma Serrano-García, “Resilience, Coloniality, and Sovereign Acts,” 4.

[34] Ibid.

[35] This is largely due to policies like the Jones Act which subsidize U.S. shipping and products at such a rate that Puerto Ricans cannot afford the premium attached to locally grown products. For more information, see: “How the U.S. Dictates What Puerto Rico Eats” by Israel Meléndez Ayala and Alicia Kennedy, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/01/opinion/puerto-rico-jones-act.html?referringSource=articleShare.

[36] Meghie Rodrigues, “Puerto Rico Adapts to a Changing, Challenging Environment,” UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, April 22, 2021. https://eos.org/articles/puerto-rico-adapts-to-a-changing-challenging-environment.

[37] Camila Bustos, “The Third Space of Puerto Rican Sovereignty: Re-imagining Self-Determination Beyond State Sovereignty,” Yale Journal of Law and Feminism 32, no. 1 (2020): 99.

[38] Leah Kirts, “How El Departamento de la Comida Fights Colonialism Through Food,” them, October 21, 2022. https://www.them.us/story/el-departamento-de-la-comida-tara-rodriguez-besosa-puerto-rico-food-farming.

[39] Kirts, ““How El Departamento de la Comida Fights Colonialism Through Food,” https://www.them.us/story/el-departamento-de-la-comida-tara-rodriguez-besosa-puerto-rico-food-farming.

[40] Additionally, El Depa challenges coloniality on the island through the existence of its resource library, “which includes a collection of seeds from native plants, books about the plant history of Puerto Rico, Indigenous poetry, and agricultural fiction, along with a tool library stocked with equipment for farming, small-scale construction, volunteer projects, and emergency response” (Kirts).

[41] Momo Wilms-Crow, “‘Desde Abajo, Como Semilla’: Puerto Rican Food Sovereignty as Embodied Decolonial Resistance” (Honors Thesis, University of Oregon, 2020): 48.

[42] Momo Wilms-Crow, “‘Desde Abajo, Como Semilla,’” 48.

[43] Again, my thesis is not focused on exploring what this relationship would look like in practice. Rather, I am simply imagining an alternative future informed by the work of Puerto Ricans on the island. The next step for this project would include drawing from Escobar’s Designs for the Pluriverse to figure out how to “design” or “operationalize” the suggestions put forth in my thesis project.

[44] At the time of writing, the Puerto Rico Status Act has only passed the U.S. House of Representatives. Additionally, the question of legality gets into the territory of theories of recognition (see Coulthard, Red Skin, White Masks). Working through questions of recognition would be another line of inquiry for future iterations of this project to consider/expand upon.

[45] While this might be the case, prefigurative movements on the ground in Puerto Rico could and would most likely persist in the face of a lack of Congressional certification. That being said, as I argued in Chapter 2, without fundamentally challenging the ongoing colonial relationship between the United States and Puerto Rico, true decolonization will not occur. So these prefigurative movements would simply be trying to reform the system, not contributing to its transformation.

[46] See Daniel Immerwahr, How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States (New York:

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019).

[47] For example, the issue of what to do about Puerto Rico’s debt is another question I believe to be essential to address in order to achieve decolonial justice for the island.