By: Ila and Katelin

With an ever-growing body of post-colonialist thought surrounding European colonization of non-European entities, it is important to reflect inward to see how such nations have and continue to colonize peoples within their own borders. In the case of Scotland, independence has been, and continues to be, a centuries-long dilemma. Through which England’s rule has controlled national identity and expression, as witnessed through the erasure of the laird system and outlawing of various cultural practices. However, the history of Scottish colonization is anything but clear-cut. Throughout its history, it has carried out its own forms of colonial rule, with the encroachment on Indigenous territory in North America and the Darien Scheme serving as but two examples. From this, we must ask ourselves how to contextualize Scotland as a subject of colonization. In what ways has colonization been forced upon Scotland? What technologies perpetrated its rule? How did Scotland use these technologies to colonize other peoples? What is the state of Scottish existence today? How should we go about reconciling Scotland’s place as both a colonized and colonizing entity?

Scotland as colonized

While Scotland was first declared as a feudal dependency of England in the late 13th century, active oversight by the English crown and its subjugation under the “imperial” throne of “Great Britain” was not imposed until 1603. Since then, several failed rebellions against the British Empire resulted in legislation intended to culturally erase Scottish heritage and establish hegemony with the English governing body. Through the Statues of Iona and Heritable Jurisdictions Act 1746, the British government dismantled the Highlands chiefdoms, disenfranchised the Scottish judicial system, and outlawed tartan and kilts, the speaking of Gaelic, and several other cultural practices.[1] However, by far, one of the most insidious practices was the control of presumably neutral industries for the enforcement of colonial rule. Similar to the Nil Darpan Affair, the British government systematically targeted and abolished anti-colonial media in order to force civil opinion, at least superficially, in favor of the colonialist regime.[2] From this existed “the relation between the state and those relatively autonomous institutions of public life that are supposed to constitute the domain of civil society.” [3]

Scotland as colonizer

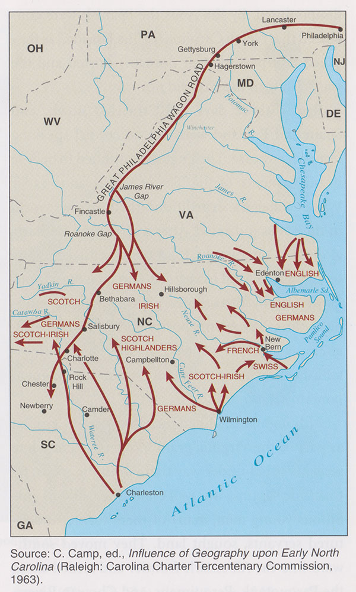

While Scotland may have a deep history of subjugation under the British Empire and the systems of colonization which went with it, “Scotland itself became an imperial nation within the British state.” [4] Most notably with the spread and influence of Scottish colonists throughout North America during the 18-19th century and the Darién Scheme. In North America, the purchase of land surveyed by the English planted newly arriving Scottish colonists on land occupied by Native Americans, who were then dispossessed of their territory.[5] In North Carolina, Cherokee, Tuscarora, and Lumbee are some of the surviving nations who directly experienced Scottish colonization.[6] Furthermore, Scottish educators and missionaries established “assimilative efforts among Native Americans” as traders and merchants skewed markets in their favor.[7] While these actions may not have been directly sanctioned by the Scottish Parliament, it can still be said that many Scots found advancement in the British Empire, became avid colonizers themselves, and forged new opportunities” through colonization.[8]

While bottom-up colonization remained prevalent throughout North America, top-down colonization was also prevalent. The attempted establishment of New Caledonia on the Isthmus of Panama, commonly referred to as the Darién Scheme, serves as an instance of state-organized colonialism by the Kingdom of Scotland. From 1698-1700 the established Company of Scotland Trading to Africa and the Indies, a rival to the English East India Company, sanctioned and funded expeditionary efforts to establish a colony at Darién in Panama for the purposes of establishing military and economic control of the region.[10] While famine and Spanish military intervention resulted in the colony’s failure, it still stands as one of the most blatant examples of a Scottish state-organized colonial effort.

Furthermore, the Darién scheme and North American enterprises serve as two examples of Scottish colonization, as evidenced by colonial efforts in the Caribbean, Asia, and Africa; they are by no means stand-alone phenomena.[11] From this arises several questions. As subjects of the British Empire, to what degree should Scottish colonialism be separated from that of its colonizer? What degree of agency should be afforded to Scottish colonists themselves, the institutions they represented, and the state that oversaw it all? As Scotland seeks referendums for its own independence, how, if at all, should its colonial history bear influence?

21st-century independence movements

Over half a decade after the Brexit referendum and what many, including the present prime minister, described as a “once-in-a-generation opportunity,” there has been some discussion surrounding the mobilization of indyref2, another referendum. Originally, the people of Scotland had voted 55-45 in 2014 to stay in the UK, but this was prior to Brexit.[12] As a result of Brexit, the prevalence of economic, trade, education, and government harm has increased in Scotland. Yet from an article published this past November, statistics show split support for indyref2, with 49% supporting independence and 51% against it when “don’t know” votes are included.[13] With further complications coming from a recent supreme court case stating that Scotland cannot unilaterally hold a second referendum, pro-independence parties view this as a block to Scottish democracy. The current prime minister Nicola Sturgeon stated on Twitter that “A law that doesn’t allow Scotland to choose our own future without Westminster consent exposes as myth any notion of the UK as a voluntary partnership & makes (a) case” for independence.”[14] Yet she hasn’t lost hope for the referendum and believes that the 2025 election cycle will be a single-issue vote for independence.[15] However, the prevailing political climate surrounding the furtherance of the referendum is generally pessimistic, with the odds of people being swayed one way or the other unlikely, with fewer undecided voters now than there were in 2014.

In the past, the unique history of Scotland as both a colonizer and the colonized has shaped Scottish society in a way that is dissimilar to any other to nearly any other place in the world. Scotland’s past as a colonizer and the colonized continues to permeate society through language, religion, and art, as it is a mixture of what has been imposed on the Scottish people and what has been taken via imperialism. This creates significant issues when it comes to complicated ties between Scotland and the UK, especially financially, as Scotland would be under no legal bounds to bear the weight of the UK’s debt following independence. Yet the supreme court ruling in November barred most hope of independence at least until 2025. We will likely continue to see Scotland separating itself from the UK in other ways by not giving into Westminster whims and continuing to rally in support for a second referendum until the next election in 2025, where the now prime minister believes that the referendum could gain some real traction.

[1] Tom M. Devine, Clanship to Crofters’ War: The social transformation of the Scottish Highlands, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1994), 11-17; Michael Lynch, Scotland: a New History (London; Pimlico, 1992) 304.

[2] Partha Chatterjee, “The Colonial State” in The Nation and Its Fragments (Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2003) 22.

[3] Partha Chatterjee, “The Colonial State” in The Nation and Its Fragments, 22.

[4] Colin Galloway, “‘Have the Scotch no Claim upon the Cherokees?’ Scots, Indians and Scots Indians in the American South,” in Global migrations; the Scottish diaspora since 1600 (Edinburgh; Edinburgh University Press, 2017), 77.

[5] Charles R. Holloman, “John Lawson 1674-1711,” in Documenting the American South, UNC press, accessed February 6, 2023, https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/lawson/bio.html.

[6] Colin Galloway, “‘Have the Scotch no Claim upon the Cherokees?’,” in Global migrations, 78.

[7] Colin Galloway, “‘Have the Scotch no Claim upon the Cherokees?’,” in Global migrations, 77.

[8] Colin Galloway, “‘Have the Scotch no Claim upon the Cherokees?’,” in Global migrations, 77.

[9] David Goldfield, “Early Settlement,” NCpedia, October 2022, https://www.ncpedia.org/history/colonial/early-settlement

[10] Dennis Hidalgo, “To Get Rich for Our Homeland: The Company of Scotland and the Colonizaiton of the Darién,”Colonial Latin American Historical Review (2001): 5.

[11] Angela McCarthy and John MacKenzie, “Introduction Global Migrations: The Scottish Diaspora since 1600” in Global migrations; the Scottish diaspora since 1600 (Edinburgh; Edinburgh University Press, 2017), 20.

[12] Meilan Solly, “A Not-So-Brief History of Scottish Independence,” Smithsonian Magazine, January 30, 2020. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/brief-history-scottish-independence-180973928/.

[13] BBC News, “Scottish Independence: Will There Be a Second Referendum?,” November 23, 2022. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-scotland-politics-50813510.

[14] Rob Picheta, “Scotland Blocked from Holding Independence Vote by UK’s Supreme Court.” CNN, November 23, 2022. https://edition.cnn.com/2022/11/23/uk/scottish-indepedence-court-ruling-gbr-intl/index.html.

[15] Rob Picheta, “Scotland Blocked from Holding Independence Vote by UK’s Supreme Court.”

[16]Petere Davidson, “Scottish Independence Supporters to Consider Holding Indyref2 Protests in London.” Daily Record, May 27, 2021. https://www.dailyrecord.co.uk/news/politics/scottish-independence-supporters-consider-holding-24197271.