Jackson Plemmons, Jenny Huang, and Michael Baird

Introduction: Representing Non-Linear Time

Ugandan author Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s 2014 novel Kintu simultaneously tells the story of one family as it unfolds over multiple generations. The book opens with the 2004 death of Kamu Kintu who is murdered in a suburb of Kampala after being falsely accused of theft before turning to Kintu Kidda, the ruler of a Baganda province who in 1754 accidentally kills his son. Readers of the novel follow the resulting “curse” as it manifests in successive generations before reaching Kamu; however, Makumbi subverts the Western convention of chronological narrative with its implied causal relations—notably and pertinently often employed in the tracing and validating of royal lineages—by having the story progress in each time period a little at a time before switching to another.

Rather than linear chronology, the resulting narrative resembles something like French philosopher Bruno Latour’s imagining of time as a spiral in which certain moments in the (chronologically) more distant past echo the present to a greater degree than the more recent past (Latour 1993, 75). Perhaps, even, the narrative is circular with the past continually playing out and collapsing into the present. In writing Kintu, Makumbi drew upon what she identifies as an emic Ugandan paradigm of time in which “the dead are not with us but are still with us” (Underwood 2017). It is the same one in which every set of twins is given an identical set of names. Simultaneously, they are an individual, an ancestor, a return, and a collective.

“Railway Time” in British East Africa

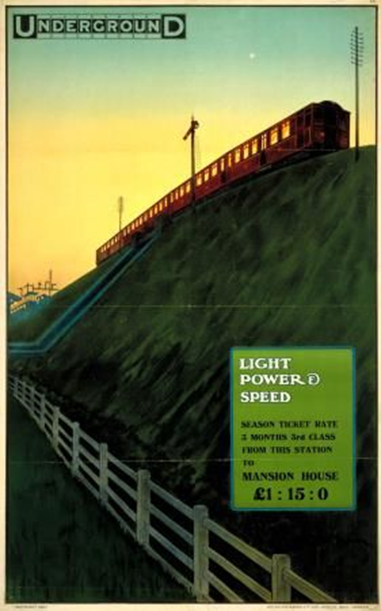

The British, in colonizing Uganda, exported their conception of linear time in a number of ways. Unidirectional, teleological time was a prerequisite for the civilizing and evolutionist rhetoric of the colonial project, but this temporal imaginary was not just a discursive formation. It also arrived in East Africa on a technology of rule that remade time and space in the region—the Uganda Railway.

The Uganda Railway, built between 1896 and 1901, was named for its final destination, but the track itself only ran from the Indian Ocean to Lake Victoria (Whitehouse 1948 and Carnegie Museum of Natural History). The Uganda Protectorate could then be reached by steamship. Reliable and consistent travel by train or steamer necessitated the establishment of regular and standardized time. Local temporalities and even the individual experience of time with its accelerations, decelerations, and multiplicities were reordered and challenged by time that only moved forward in a predictable and uniform manner. (On the experience of time see, for instance, Lefebvre 2004.) Unsurprisingly, the British placed themselves as the longitudinal center of the world from which time zones became measured.

The ontological and material ruins of the Uganda Railway continue to shape the political and economic landscape of the region. In Uganda, the development-focused National Resistance Movement political party, which has been in power for almost four decades, is reportedly attempting to work with a Turkish company to complete a project that the British never could—building a railway from the Kenyan border to the interior of the country (Reid 2017, Ngila 2023, and “Achievements”). The Kenyan Railways Corporation still utilizes the original route of the Uganda Railway, and the architects of the stalled Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia-Transport Corridor project have intentionally drawn on the historical precedent of the Uganda Railway in emphasizing the potential for similar “expansion and development” in northern Kenya (Asselmeyer 2022 and Aalders 2020).

The Colonial Ghost of Kenya: Land Privatization

Drought, violence, famine, poverty, and corruption are all too common in the rural pastoralist communities of Kenya. In many ways, the experience of modern Kenyan pastoralists is a product of colonial occupation by the British from 1895 to 1963. The legacies of colonialism bleed into modern day culture, infrastructure, and politics among other aspects of daily life. In this section, we will explore the implications of neoliberalism, modernity, and temporality in the context of pastoralist communities in Kenya. Specifically, modern policies favoring the privatization of tribal land and its connection to climate change will be discussed, drawing on both personal experience and outside sources.

According to the World Bank, 93% of Kenyans in 1960 lived in rural communities which has steadily decreased to 72% of Kenyans in 2021. The majority of the rural population are pastoralist tribes, meaning they live off the land, herding animals and growing crops in small pockets of tribal communities. An estimated 9 million pastoralists still inhabit Kenya.

There are two main types of pastoralists: highlanders and lowlanders. Lowlanders live in lower altitudes, and consequently, more arid conditions not suitable for settling down permanently. Lowlanders are mostly nomadic and move settlement areas once the resources in that area cannot sustain grazing. In contrast, highlanders live in high altitude areas and receive more rain, which allows for more permanent settlements. Highlanders tend to own more livestock and are more wealthy in general than lowlanders. Both highlanders and lowlanders are often affected by long droughts and extreme starvation, with the lowlanders often experiencing more brutal conditions.

Before the British occupation, the lands inhabited by pastoralists were communally owned by each tribe, and land was generally free to graze. The British attempted to privatize land ownership in the 1950s, reasoning that private land ownership would lead to more sustainable land use and less degradation of resources. Recent research concluded that land subdivision “does not precipitate ecological sustainability in arid and semi-arid areas” (Rozen 2016). Before land privatization, “pastoralists could respond to seasonal variation and drought by moving freely across the land to find adequate grazing for their animals” (Rozen 2016). Climate change combined with land privatization has increased the length and strength of droughts, with Northern Kenya experiencing one of its worst droughts in history concurrently.

In addition to the environmental impact, land privatization leads to more conflict and violence between neighboring pastoralist tribes. The concept of ownership has led tribal warriors to steal or kill any animals from another tribe that enter their land, which leads to human on human violence often in the form of gunfights.

Like a haunting colonial ghost, land privatization continues to this day, having adverse effects and uprooting cultural traditions in favor of modernity, and amplifying the effect of climate change.

Tanzania: Limitations of Growth in the Modern Day

Tanzania, an East African country, is currently experiencing vast growth economically, socially, and politically. It has been deemed as “becoming one of the best investment destinations in the world” (Okafor 2023). The country being viewed in an economic sense in terms of its utility and resources it can provide for the world is a repetition of history that can be seen when Tanzania was first colonized by Germany in the 1880s (Ingham et al. 2023). After World War I, the country came into the possession of the British and independence from Britain was finally gained on December 9, 1961.

Tanzania existed as two separate entities in the colonial period, Zanzibar and Tanganyika (Ingham et al. 2023). The colonization of Tanzania left the country vulnerable and lacking the proper tools to prosper. The early post-colonial era was characterized by violence in the form of riots and revolutions. For example, the Zanzibar Revolution of 1964 took place when the African majority engaged in anti-Arab violence against Arab elites (Eddoumi 2021). These events proved to be pivotal in the merging of Zanzibar and Tanganyika into the Tanzania we know today.

Marks of colonialism manifest itself in contemporary life as seen by its largely agrarian economy, low quality public services, and corruption and inefficiencies of the government. The agriculture sector accounts for one quarter of the country’s GDP and employs three quarters of all Tanzanian workers (Machangu-Motcho and Rispoli). Furthermore, the land faces degradation issues because of unstainable farming practices, climate change, poverty, political instability, and insecure land tenure system (Kamuzora and Majule 2018). Additionally, the country faces issues of equitable access to public services. There is a disparity between the quality of services rural and urban areas receive. Reforms have been made to decrease corruption in the government as shown by the establishment of the Prevention and Combating of Corruption Bureau (PCCB); however, it is a pervasive issue that continues to affect all sectors such as government procurement, land administration, taxation, and customs (Hoseah 2008).

Although post-colonial Tanzania has made great strides in terms of political, social, and economic improvement, the country still grapples with issues that can be rooted in its colonial past. It shows that hauntings from the past continue to affect Tanzania’s livelihood in both visible and invisible ways.

Bibliography

Aalders, Johannes Theodor. “Building on the Ruins of Empire: The Uganda Railway and the LAPSSET Corridor in Kenya.” Third World Quarterly, vol. 42, no. 5, 2020, pp. 996–1013.

“Achievements.” Achievements | National Resistance Movement, https://www.nrm.ug/achievements. Accessed 22 Mar. 2023.

“A Guide to the United States’ History of Recognition, Diplomatic, and Consular Relations, by Country, since 1776: Kenya.” U.S. Department of State. U.S. Department of State. Accessed March 22, 2023. https://history.state.gov/countries/kenya#:~:text=The%20United%20States%20recognized%20Kenya,independence%20on%20December%2012%2C%201963.

Asselmeyer, Norman. “Ruin of Empire: The Uganda Railway and Memory Work in Kenya.” Journal of Educational Media, Memory, and Society, vol. 14, no. 1, Mar. 2022, pp. 14–32.

Eddoumi, Nabil. “The Zanzibar Revolution of 1964 .” The Zanzibar Revolution of 1964, Black Past, 29 Nov. 2021, https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/events-global-african-history/the-zanzibar-revolution-of-1964/.

Hoseah, Edward. Corruption in Tanzania: The Case for Circumstantial Evidence. Cambria Press, 2008.

Kamuzora, Faustin, and Amos Enock Majule. 2018, pp. 12–13, United Republic of Tanzania Land Degradation Neutrality Target Setting Programme Report.

Karuka, Manu. Empire’s Tracks: Indigenous Nations, Chinese Workers, and Transcontinental Railroad. University of California Press, 2019.

Latour, Bruno. We Have Never Been Modern. Translated by Catherine Porter, Harvard University Press, 1993.

Lefebvre, Henri. Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life. Continuum, 2004.

Makumbi, Jennifer Nansubuga. Kintu. Transit Books, [2014] 2017.

Mascarenhas, Adolfo C., Kenneth Ingham, Frank Matthew Chiteji, and Deborah Fahy Bryceson. “Tanzania”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 21 Mar. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/place/Tanzania.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark. “Current and Future Challenges and Opportunities in Tanzania.” Current and Future Challenges and Opportunities in Tanzania, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, Apr. 2014, https://um.dk/en/danida/strategies-and-priorities/country-policies/tanzania/current-and-future-challenges-and-opportunities-in-tanzania.

Ngila, Faustine. “Uganda Courts Turkey to Build Its Railway, Cancels China Contract.” Quartz, 13 Jan. 2023, https://qz.com/uganda-is-now-courting-turkey-to-build-its-railway-1849983843.

Okafor, Chinedu. Tanzania Is Fast Becoming One of the Best Investment Destinations in the World, Business Insider, 14 Mar. 2023, https://africa.businessinsider.com/local/markets/tanzania-is-fast-becoming-a-top-investment-destination/4wtk1gv.

Reid, Richard J. A History of Modern Uganda. Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Rozen, Jonathan. “Land Privatisation and Climate Change Are Costing Rural Kenyans.” ISS Africa, November 30, 2016. https://issafrica.org/iss-today/land-privatisation-and-climate-change-are-costing-rural-kenyans.

“Rural Population (% of Total Population) – Kenya.” Data. Accessed March 22, 2023. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS?locations=KE.

“Uganda Railway.” Carnegie Museum of Natural History, https://mammals.carnegiemnh.org/childs-frick-abyssinian-expedition/uganda-railway/.

Underwood, Alexia. “So Many Ways of Knowing: An Interview with Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi, Author of ‘Kintu.’” Los Angeles Review of Books, 31 Aug. 2017, https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/so-many-ways-of-knowing-an-interview-with-jennifer-nansubuga-makumbi-author-of-kintu/.

Whitehouse, G. C. “The Building of the Kenya and Uganda Railway.” The Uganda Journal, vol. 12, no. 1, Mar. 1948, pp. 1–15.