Presentation Slide Image:

Explication of Research:

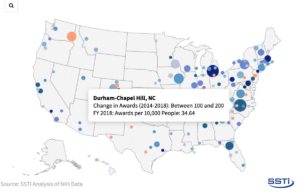

The funding needed versus the funding currently being allocated to Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) research is a widely debated topic in the medical research community. There is a gap in the literature in explaining why ALS is an underfunded terminal illness: ALS has been given orphan disease status, a status used to signify a disease that is neglected due to its rarity and therefore the lack of financial incentive for pharmaceuticals to pursue a cure, despite it exceeding the maximum prevalence threshold for an orphan disease. The sad reality is that ALS is not an orphan disease or a rare disease given its prevalence statistics, but simply a neglected disease, and a terminal one at that (Grisold et al., 2019, p. 9). Additionally, there is another gap in the proposals of legitimate methods to alleviate this problem. This disconnect is especially frustrating in a state like North Carolina, where medical research is integral to the identity of the state and is a primary draw in bringing many bright minds from all over America and the world to the state (Haskins, 2019, para. 4). Prominent, reputable research organizations in North Carolina lacking funding, patients and families being unable to advocate, and the lack of a non government sponsored annual fundraising event illustrate the need for additional advocacy to increase awareness and funding for ALS; reaching out to Congress with patient stories, establishing the non-political nature of medical research funding, and elevating one-time fundraisers to annual events through through outlined methods are the ways we can go about this advocacy.

The NIEHS–a sub-organization of the NIH (National Institutes of Health) located in the Research Triangle region of North Carolina–believes in a nuanced interplay between genetics and environmental exposure in their pursuit to determine the cause of ALS. While countless studies and research groups create a question that oversimplifies ALS pathology, testing for either genetics or environmental factors–quite frankly since they are more likely to find a correlation that is straightforward and therefore more desirable by the general public–the integrity and holistic approach of this North Carolina based organization is admirable. This is the type of research that is far more likely to provide the critical information that may not make headlines to the layman immediately but will undoubtedly be useful as a part of the bigger picture on the quest for a cure. Unfortunately, the ideas-ready-to-be-tested to funding-available ratio for this organization is high , and instead of being able to focus solely on the aforementioned research, principal investigators must instead spend a great deal of their time and energy navigating the NIH system for funds, and it’s likely that many great ideas never come to fruition for that reason. (Chad et al., 2013, p. 62-66).

The need for public health scholars and politicians to be educated on the cause and key forces in the battle against ALS is due to the fact that ALS is an illness for which many of its patients and their family members are unable to be advocates, for reasons specific to the timeline and course of the illness. For example, in the time period after diagnosis, while a patient’s motor skills are still present and functioning, the mental toll of coping with the diagnosis makes it nearly impossible to engage deeply in advocacy. The family, anticipating disease-associated loss in the near future, is in the same predicament. As the disease quickly progresses, the patient’s motor skills diminish, putting the emphasis on just dealing with day to day life. In the end of life stage, the patient experiences a near complete loss of communication skills while the family, during this stage and in the next stage of coping with disease-related loss, are often too physically and psychologically exhausted to be vigorous advocates for ALS (Grisold et al., 2019, p. 9).

In an ideal world, ALS has an event that provides it with a dependable stream of annual funds. Unfortunately, despite all the press it got during its period of fame, the Ice Bucket Challenge was short lived and did not change the long term outlook. Yes, it did bring in donations at that time which can never be taken away, so it did have a net positive impact on the field of ALS research. That being said, looking at the before and after statistics, we can see that it did not stimulate any public interest in ALS still felt to this day–the Wikipedia page on ALS started at 3,000 views a day before the Ice Bucket Challenge, then went all the way up to a peak of 450,000 views in a single day during its peak, only to return right back to normal. Why the ALS community needs a flagship annual fundraiser is since without it, ALS is much more dependent on federal funds than other illnesses that have the non-government provided funds to fall back on as the government NIH funds fluctuate each year. As I begin to address the second half of the research question, I circle back to this and propose some methods on how we should go about establishing an annual event like this (Wicks, 2014, p. 479-480).

Brian Wallach had a story, which was enough to secure a significant chunk of funding for ALS research–100 million to be exact. Yes, the 100 million dollar ACT for ALS Act was made possible in large part due to advocacy, to taking the initiative to share stories. Here’s the amazing part: it wasn’t Brian’s story alone. In fact, this was the result of many ALS patients sharing excruciatingly similar stories: stories of physical deterioration, stories of a sense of helplessness from the time they were diagnosed to the soon thereafter realization that they don’t have very much time left with their loved ones. This was not to seek pity from congressmen and women as that is not an objective of any ALS patient or caretaker. Rather, the purpose was to paint a brutally objective and picture of the life of an ALS patient. Wallach was a former lawyer who knew how Washington worked. What he also knew was you didn’t have to be someone who knew the ins and outs of Washington to be able to have an impact on getting this bill passed–you just needed to have a story, yours or someone else’s, to be able to further humanize the situation for those in positions of political power. This is why he not only shared his own story, working as a White House Counsel during Obama’s presidency, but gathered a group of ALS patients to share their stories, and in doing so created a rally (Strom, 2022, para. 22). This quote from Wallach himself sums it up best:

“‘I will not see my daughters grow up,’ he said. His pace was methodical, owed to the practice sessions he’d done. There was only a slight strain in his voice. ‘There is no cure. Not because ALS can’t be cured but because we have underfunded the fight against ALS year after year after year. I know this committee doesn’t often hear from people with ALS. You don’t because ALS is a relentless churn. We diagnose. We die, quickly. We don’t have time to advocate.’”

There are reports of special interests in Washington in favor of decreasing national research funding but not with the intention of cutting research funding outright, as this is almost sure to be received with near unanimous public disapproval, but rather to give themselves the flexibility to choose what is deserving and not deserving of funding. Essentially, instead of leaving a designated amount to be divided up by experts in healthcare and public health, these congressional politicians would like to cut this baseline support to all causes so they can then allot the remaining balance of funds towards hot button health issues to get more votes. This would undoubtedly lead to misallocation of funds and therefore, a loss of human lives. In efforts to reach out to local congressmen and women, whether it’s a phone call, a letter, or even a brief email, expressing your thoughts on the ethical concerns of such a move would have a significant impact in deterring anyone from taking such an action since at the end of the day, the dragging of healthcare research into the field of politics would be done only with the sole purpose of political gain. If there are any signs of the move potentially backfiring and causing a controversy of any magnitude in the public eye, it will have a great impact in deterring such politicians. While we are currently looking at this from a prospective perspective, it is fair to speculate whether the occurrence of this on a smaller scale behind the scenes throughout history has in part led to the current situation of ALS being a grossly underfunded terminal illness. Regardless, writing to politicians to express your concern about leveraging an issue this serious to fulfill ulterior motives can only have a net positive impact on the outlook of this situation (Epstein, 2011, p. 1).

As referenced previously, the Ice Bucket Challenge was an amazing event and did make an impact but unfortunately, didn’t create any sustainable, long term change with regards to ALS funding. However, that doesn’t mean that it can’t. In fact, there is precedent for a movement very similar to this one being sustained for a different health issue: ‘Movember’, the growing of mustaches in November to raise awareness for men’s health issues. This too began as a one time event, but has since been elevated to an annual event that positively contributes to annual prostate cancer funding. How so? There is no one singular reason but there are a few lessons we can takeaway and apply to either the Ice Bucket Challenge or to an entirely new ALS fundraiser event. First, there is an established time period of the year associated with this event, which gives way to it being an annual event. Additionally, a month is not too long of a time period to dilute the focus but at the same time long enough to gather the requisite attention. Secondly, the action of the fundraiser ties in (to a greater degree) to the cause they are raising funds for, which is key to the action being memorable enough to warrant annual replicability in the minds of those who do not have strong ties to the illness (Wicks, 2014, p. 1).

The reasons why additional advocacy in ALS is needed, rooted in ALS being an underfunded illness, have been laid out. No action is required on the arguments, simply deciding whether or not you agree with the logic presented. In response to the second half of the research question, however, within the explanation of methods to be an advocate and close this gap is embedded a call to action. For those who happen to know or knew someone who had ALS, simply writing a letter to a local congressman and sharing that person’s story, no matter how in-depth or surface level you know it, would go a long way towards supporting the cause. The more names and faces those in charge can associate with this illness, the higher the likelihood for a just level of funding being allocated. As for elevating one-time fundraisers to annual events, truly anyone can reach out to their local ALS Association with ideas on how to create momentum with building annual fundraisers, perhaps even better if your perspective is as someone who has no ties to the illness. What would an event need to have for you to be willing to donate year in, year out? No extensive time commitment is necessary but by simply sharing your input and spreading the word, anyone can use their voice to be an advocate for ALS funding.

Abbreviated Script:

The funding needed versus the funding currently being allocated to Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, also known as ALS, is a widely debated topic in the medical research community. There is a gap in the literature in explaining why ALS is an underfunded terminal illness and how to go about changing that. Luckily, there are multiple pieces of evidence that show how and why ALS is underfunded, and potential steps we can take to alleviate this issue. The relevance of medical research funding as a whole to the state of North Carolina is referenced here in this visual aid. It is a big part of our identity as a state.

Many patients and family members are unable to be their own advocates, due to the specific nature of the illness. The mental toll for patients and families immediately post-diagnosis, followed by the patient’s loss of ability to communicate, followed by physical and psychological exhaustion from the caregivers after the patient’s death makes for disease timeline not conducive for advocacy by any member at any point.

To the potential counterpoint of the immediate success of the Ice Bucket Challenge in spreading awareness, it should be noted that the Ice Bucket Challenge did not change the long term outlook of ALS awareness and annual funding. The Wikipedia page on ALS started at 3,000 views a day before the Ice Bucket Challenge, and while it did go all the way up to a peak of 450,000 views in a day, it returned right back to normal.

While the Ice Bucket Challenge did not go on to become ALS’s flagship annual fundraising event, that does not mean that ALS can not have one. To create an event of that mold, it is important that there is an established time period of the year associated with this event. Furthermore, the action of said fundraiser must to a greater degree tie in to the cause and the patients it is representing. With those two steps, it will be possible for ALS to have a flagship annual fundraiser like other illnesses to make it less dependent on federal funding.

Lastly, we must not politicize medical research funding. Allow public health professionals to fully handle the divvying up of research funds and to advise politicians on determining the net total of research funding, within reason. This, along with increased advocacy, should correct the problem over time.

I have tremendous hope that with the right intentions and requisite knowledge as a society, we can find a way to generate more funds for ALS research to be able to tackle this illness and one day find a cure.

References:

Chad, D. A., Bidichandani, S., Bruijn, L., Capra, J. D., Dickie, B., et al. (2013). Funding agencies and disease organizations: Resources and recommendations to facilitate ALS clinical research. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Degeneration, 14(sup1), 62–66. https://doi.org/10.3109/21678421.2013.778588.

Epstein, J. A. (2011). Politicizing NIH funding: a bridge to nowhere. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 121(9), 3362–3363.https://doi.org/10.1172/jci60182.

Grisold , W., Struhal, W., & Grisold, T. (2019). Advocacy in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. In Advocacy in Neurology. In Google Books. Oxford University Press. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=7BqJDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT271&dq=amyotrophic+lateral+sclerosis+advocacy&ots=sLB0SnTyzL&sig=JRX__RqAyUG40L1KCLtH1Fqg0i4#v=onepage&q=amyotrophic%20lateral%20sclerosis%20advocacy&f=false.

Haskins , B. (2019). Triangle leads nation in NIH per-capita funding. North Carolina Biotechnology Center. Retrieved February 26, 2022, from https://www.ncbiotech.org/news/triangle-leads-nation-nih-capita-funding.

Stein, S. (2022). He was given 6 months to live. Then he changed D.C. POLITICO. Retrieved March 17, 2022, from https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/01/14/brian-wallach-als-advocacy-527094.

Strom, R. (2022). Big law associate fights ALS from “death sentence” to “dream.” Bloomberg Law. Retrieved February 26, 2022, from https://news.bloomberglaw.com/business-and-practice/big-law-associate-fights-als-from-death-sentence-to-dream.

Wicks, P. (2014). The ALS Ice Bucket Challenge – Can a splash of water reinvigorate a field? Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Degeneration, 15(7-8), 479–480. https://doi.org/10.3109/21678421.2014.984725.

Reference [for Presentation Slide]:

Triangle leads nation in NIH per-capita funding. Duke | Translation & Commercialization. (2019). Retrieved March 19, 2022, from https://otc.duke.edu/news/triangle-leads-nation-in-nih-per-capita-funding/.

Featured Image Source:

Stein, S. (2022). He was given 6 months to live. Then he changed D.C. POLITICO. Retrieved March 17, 2022, from https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/01/14/brian-wallach-als-advocacy-527094.