Slide References :

[NCDHHS] North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. (2022, Feb. 28). Vaccinations. North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://covid19.ncdhhs.gov/dashboard/vaccinationsTippett, R. (2021, August 12). First look at 2020 Census for North Carolina. Carolina Demography. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://www.ncdemography.org/2021/08/12/first-look-at-2020-census-for-north-carolina/

Vasudevan, L., Walter, E., & Swamy, G. (2021). Vaccine Hesitancy in North Carolina: The Elephant in the Room? North Carolina Medical Journal, 82(2), 130–137. https://doi.org/10.18043/ncm.82.2.130

Script:

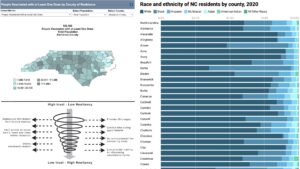

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a puzzling trend across the North Carolina has been the relatively low amount of black people getting vaccinated. I associate being vaccinated with Democrats, and know black people vote overwhelmingly Democratic, so I thought “what gives?” For my research, asked the question of: Why is there a racial vaccination disparity in North Carolina? To solve the issue, I will argue that we need to invest in black communities with properly funded clinics, while hiring black medical professionals to create representation for those who feel forgotten in the white-dominated healthcare system.

The “elephant in the room” for vaccine hesitancy is the Tuskegee study, where doctors in the 1900s unethically avoided treated black men with syphilis. Sociologists argue this issue is overemphasized in explanations of vaccine hesitancy and marginalizes other problems of the healthcare system. Tuskegee has become a symbol of helplessness, implying we can no longer fix the issue of black vaccine hesitancy. If we want to fix the disparity, we must acknowledge Tuskegee but avoid the idea that nothing can be done.

More than 55% of doctors nationwide are white and 5% are black, meaning many black people must settle for a white doctor. This may seem insignificant, but research shows that Black people will wait months longer to be served by a black doctor. A solution to this problem is to train and hire more black medical professionals. If more resources can be put into diversity at vaccination clinics throughout North Carolina, more vaccinations will occur.

Largely black counties have relatively less medical resources than white communities, and this is often unaccounted for in studies. Vaccination meta-analyses show that researchers often incorrectly assumed that vaccines arrived at the same time for each county, and vaccine clinics are equally accessible. Further, some people may fear they are immunocompromised, but cannot get testing. It is clear that in poor North Carolina counties, becoming vaccinated is more complex than walking into a CVS.

Counties like Northampton are some of the poorest in North Carolina. This creates ambiguity if majority-black counties truly are refusing the vaccine at higher rates, or if other factors are in play. Research shows that vaccine hesitancy correlates with low socioeconomic status, creating an alternative hypothesis. This implies that the cause of vaccine hesitancy could be better correlated with a socioeconomic factor in unvaccinated counties. The reason true behind vaccination could be an opportunity for further research.

In the long run, investing in black communities to encourage more black physicians is another possibility. North Carolina is a diverse state with countless backgrounds, ethnicities, and identities, and we must reflect that in medicine. One shorter-term solution is more investment in underserved communities, creating high-quality clinics and healthcare facilities. Research suggests that the disparity in resources between counties could lead to the differences in vaccination status, not just race. Overall, if we invest in black communities, the racial gap in vaccinations will decrease throughout North Carolina and the entire United States.

Explication of research

Since the COVID-19 vaccine began distribution to the general public during the spring of 2021, North Carolina has scrambled to get enough citizens vaccinated. One puzzling trend across the state has been the lack of black people getting vaccinated compared to other races (Bajaj & Stanford, p. 1). Census data shows that most of the most unvaccinated counties in the state, for example Currituck and Northampton (NCDHHS, 2022, para. 3), have some of the highest proportions of black people in the state (Tippet, 2021, para. 15). I began my research by asking the question: Why is there a racial vaccination disparity in North Carolina? My argument is that to solve this issue, we need invest in black communities with properly funded hospitals and clinics in the short term. In the long term, we need to invest in education to train more black doctors and medical professionals, all while learning from the healthcare industry’s previous mistakes.

When asked about the reasoning behind the racial disparity in vaccinations, most pundits mention the well-known Tuskegee Syphilis study in the early 1930s (Schumaker 2021, para 1). In this study, white doctors allowed black men with syphilis to go untreated to study the effects of the disease. Although the ethics behind the study are appalling, the doctors of today are far different than those during the 1930s and are likely eager to right the wrongs of past medical injustices. The medical community needs to reframe the events as a signal to be better instead of doing nothing. Entirely blaming vaccination disparities on Tuskegee trivializes the issue, and sways discussion from tangible solutions to the vaccination problem. Sociologists have argued that this portrayal creates a monolithic identity for black people and marginalizes other racial issues within the healthcare system (Bajaj & Stanford, p. 1). Black people have distrust in the medical system for many different reasons, which should indicate that the social capital investment into medicine for black communities should increase. This history is important, but instead of being a call of helplessness, it should provide a call of action for medical officials to rebuild trust with the black community.

Although an uncommon occurrence for white Americans, being treated by a doctor of the same race as the patient has a large impact on a patient’s willingness to receive healthcare. Thus, an important step for fixing the racial vaccination disparity throughout North Carolina is creating visibility with black doctors and healthcare professionals. Research has consistently shown that black people will go out of their way for treatment by black medical providers (Bajaj & Stanford, 2021, p. 1). More than 55% of all doctors nationwide are white and only 5% are black, meaning there is often a disparity of black people with access to a medical professional of the same skin color (AAMC. 2019, para. 1). It is imperative that the state of North Carolina hires more black doctors, while also publicizing the news to black people the opportunity to be treated by a provider of the same race. If more diversity is present at clinics across North Carolina, more vaccinations are likely to occur.

Underserved, predominantly black counties like Currituck and Northampton have been found to have fewer medical resources, but this is hard to portray in census data and other reports. Current studies often assume that vaccine supply has arrived at the same time for each county, and vaccine clinics are equally accessible, when this clearly is not the case. (Vasudevan et al., 2021, p. 134). This builds the importance of accessibility in the vaccination process, as it shows that the issues with vaccine disparity are not solely based in marketing. Data portrayal needs to become more nuanced to truly illustrate the vaccination status of North Carolina. The solution to solving the racial disparity is not a singular change. Results of research need to become more nuanced and complex to truly account for accessibility of vaccines.

Sociologists have also criticized the way data is acquired, as the current norm assumes that not getting the vaccine is “hesitancy”. A meta-analysis North Carolina’s vaccine hesitancy has shown that most research qualifies anyone without a vaccine, regardless of their ability to acquire one, as “vaccine hesitant” (Vasudevan et al., 2021, p. 134). An implication is that people who fear they are immunocompromised but cannot afford a test are counted as “hesitant”, when this clearly is not the case. In some counties, getting a vaccine is much harder than simply walking into a CVS.

Majority-black, counties with low vaccination rates like Northampton also are some of the poorest in North Carolina (NC Policy Watch, 2012, para. 4). This could create issues in seeing if black communities truly are refusing the vaccine, or if the hesitancy is due to another factor, such as socioeconomic status. Sociologists have observed strong correlations between vaccine hesitancy and low socioeconomic status, but the racial narrative is pushed harder throughout the media (Donadio et al., 2021, p. 7). An implication of this is that studies could correlate race with vaccination status when an alternative hypothesis, a low socioeconomic status, may be the true cause. Comparing the strength of correlations between race and vaccine hesitancy against socioeconomic status and vaccine hesitancy could be a topic for future research.

The racial vaccination problem is complex and needs multiple short-term and long-term solutions to be solved. One shorter-term solution is for North Carolina’s legislature to invest in underserved counties, creating high-quality clinics and healthcare facilities on par with those in rich counties like Wake. The difficulty in getting a vaccination is different across the state, and officials must be cognizant of that obstacle moving forward. In the long run, more investment into education for black communities to encourage more black physicians is a strong choice to close the vaccination gap. North Carolina is a diverse state with countless backgrounds, ethnicities, and identities, and we must reflect that in medical providers. Investing in education will create more diversity in medicine, more vaccinations across the state, and finally begin to right the injustices of Tuskegee and numerous other medical atrocities in US history.

Works cited

[AAMC] American Association of Medical Colleges. (2019, July 1). Percentage of all Active Physicians by Race and Ethnicity. American Association of Medical Colleges Retrieved March 7, 2022, from https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/figure-18-percentage-all-active-physicians-race/ethnicity-2018Bajaj, S. S., & Stanford, F. C. (2021, February). Beyond Tuskegee — Vaccine Distrust and Everyday Racism. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(5), 1-2. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmpv2035827

Donadio, G., Choudhary, M., Lindemer, E., Pawlowski, C., & Soundararajan, V. (2021 July). Counties with Lower Insurance Coverage and Housing Problems Are Associated with Both Slower Vaccine Rollout and Higher COVID-19 Incidence. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 9(9), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9090973

[NCDHHS] North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. (2022, Feb. 28). Vaccinations. North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://covid19.ncdhhs.gov/dashboard/vaccinationsNorth Carolina Policy Watch. (2012, Feb. 28). Report: 10 NC counties with High Poverty Rates for Three Decades. NC Policy Watch. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://ncpolicywatch.com/2012/01/25/report-10-nc-counties-with-high-poverty-rates-for-three-decades/

Schumaker, E. (2021, May 8). Vaccination rates lag in communities of color, but it’s not only due to hesitancy, experts say. ABCNews.com. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://abcnews.go.com/Health/vaccination-rates-lag-communities-color-due-hesitancy-experts/story?id=77272753

Tippett, R. (2021, August 12). First look at 2020 Census for North Carolina. Carolina Demography. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://www.ncdemography.org/2021/08/12/first-look-at-2020-census-for-north-carolina/

Vasudevan, L., Walter, E., & Swamy, G. (2021). Vaccine Hesitancy in North Carolina: The Elephant in the Room? North Carolina Medical Journal, 82(2), 130–137. https://doi.org/10.18043/ncm.82.2.130

Featured Image Sources :

[NCDHHS] North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. (2022, Feb. 28). Vaccinations. North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://covid19.ncdhhs.gov/dashboard/vaccinationsTippett, R. (2021, August 12). First look at 2020 Census for North Carolina. Carolina Demography. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://www.ncdemography.org/2021/08/12/first-look-at-2020-census-for-north-carolina/

Vasudevan, L., Walter, E., & Swamy, G. (2021). Vaccine Hesitancy in North Carolina: The Elephant in the Room? North Carolina Medical Journal, 82(2), 130–137. https://doi.org/10.18043/ncm.82.2.130