Hello, my name is Dylan Georges and the title of my presentation is “How Doctors use “Science” to Mistreat Black Patients”. While the recent pandemic has brought to light much of the injustice in the healthcare system, many problems remain in the dark. Awareness regarding racial minorities’ access to healthcare has grown; however, the general public must still be made aware that medical professionals have adopted racist misconceptions that have led to the mistreatment of black patients. We will determine if these disparities in pain management exist in North Carolina, as well as the historical origins for said disparities. The effects of racism carry over into almost every aspect of society, and this presentation seeks to expose the healthcare industry as one of them.

First, we will look at the potential origins of this racism that we see in the medical field today. Author John Hoberman released a revolutionary book in 2012 called Black and Blue: The Origins and Consequences of Medical Racism. The book is an in-depth analysis of racism in the medical field dating back to the post-slavery era. Hoberman makes a very important point that medical professionals are often guilty of formulating pseudoscientific ideologies based off the popular societal beliefs at the time. During the early 1900s, it was post-emancipation white guilt that drove common racist misconceptions such as the idea that black people had less sensitive nerves and were less prone to injury when compared to white people. Hoberman quotes an early 1900s psychiatrist as saying “[the black child] laughs easily, dances, sings, plays, and that usually in rags and wretchedness,” forcing the perspective that black people were unaffected by the segregation they faced (Hoberman, 2012, p. 64). This idea grew among all aspects of society. During the 1960s, many football trainers believed their black players to be “virtually indestructible and thus immune to injury”, Hoberman says (Hoberman, 2012, p. 74). As mentioned, doctors, nurses, and medical professionals of all kinds adopted these same ideas, resulting in mistreatment of pain for black people. 2012’s Black and Blue is one of the first and only representations of this issue, despite its prevalence for over a century. This further exaggerates the need to expand the discourse surrounding biological racism.

A more statistical example of this pseudoscience was published in 2016 by the University of Virginia in which about 50% of medical students supported false ideologies such as “black people have thicker skin” or “black people have less sensitive nerve endings” (Hoffman, Trawalter, Axt, & Oliver, 2016). Evidence of this kind brings attention to the frighteningly high amounts of misinformation within the medical field regarding race and pain. A re-evaluation of the training given to future professionals is a necessity to ensure that these falsehoods do not lead to more medical malpractice.

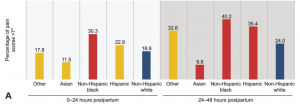

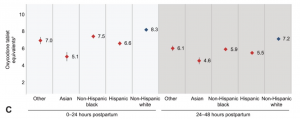

Now that we have seen the potential historical context surrounding this issue, we must analyze some present-day data. Let us look at the disparities in pain management within North Carolina. One 2019 study carried out by Obstetrics & Gynecology in Chapel Hill observed 1,701 women who had undergone cesarean birth at the NC Women’s Hospital. Post-partum, the women are given regular pain assessments and necessary pain medication corresponding to their self-reported scores. Results were measured in intervals of 0-24 hours and 25-48 hours post-partum. Scores above 7 were regarded as severe pain, requiring analgesic opiate medication, while scores above 4 were considered moderate pain, requiring non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. The study found that black women had the largest percentage of scores above 7 for both time intervals (Johnson, Asiodu, McKenzie, Tucker, Tully, Bryant, Verbiest, & Stuebe, 2019).

(Johnson et. al, 2019)

(Johnson et. al, 2019)

Black women received fewer pain assessments during both intervals when compared to white women. Regarding the medication prescribed, black women received fewer prescriptions for both analgesic and non-steroidal pain medication than white women despite having much higher levels of self-reported pain.

(Johnson et. al, 2019)

(Johnson et. al, 2019)

This evidence, although significant, is not totally concrete however, and comes with some potential sources of error. The methods of the study did not account for factors such as individual patient requests, family presence, or staff attentiveness (Johnson et. al, 2019). Be that what it may, it is still cause for alarm that black women had the highest pain scores yet received fewer pain assessments and less medication.

North Carolina is not the only state that suffers from racism in healthcare. A national meta-analysis carried out by the Journal of Pain Research found that black patients who had undergone bone fractures were less likely to receive analgesic medication for pain and more likely to receive no medication at all when compared to white people. Black patients in primary care were also less likely to receive any screenings for pain (Ghoshal, Shapiro, Knox, & Schatman, 2020). Data from the Oregon Emergency Medical Services showed similar results to that of the NC study. Researchers Jamie Kennel, Elizabeth Withers, Nate Parsons, and Hyeyoung Woo produced results showing that over a two-year period, black victims of injury had 38% higher average self-reported pain scores when compared to whites, however, were 32% less likely to receive any pain medication (Kennel, Withers, Parsons, & Woo, 2019).

In recent months, the state of North Carolina has taken this issue seriously. The NC Healthcare Association (NCHA) issued a statement in November of 2020, declaring racism a public health crisis. As part of their approach towards solving this issue, the NCHA is pushing anti-bias educational training as well as additional data collection in order to identify more possible disparities in healthcare treatment. This development is very encouraging, however it is up to the citizens to raise the standard and hold this association accountable.

Results on a state and federal level seem to indicate that black people receive inadequate pain treatment and that racist ideologies persist in the minds of medical professionals. Unfortunately, the research carried out in North Carolina is rather limited to perinatal pain management, however the results that have been produced should be cause to search for further evidence on the subject. Nevertheless, this issue is foreign to many and must be brought to the forefront of the medical discourse. Moving forward, implicit bias training should continue to be implemented and more research must be carried out to bring attention to the matter. Black families and individuals are entitled to equal treatment for their pain and without first recognizing this issue, we cannot work to ensure they are provided that. Thank you.

References

Ghoshal, M., Shapiro, H., Knox, T., & Schatman, M. E. (2020). Chronic noncancer pain management and systemic racism: Time to move toward equal care standards. Journal of Pain Research, 13, 2825-2836. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S287314

Hoberman, J. (2012). Black and blue: The origins and consequences of medical racism. ProQuest Ebook Central https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu

Hoffman, K., Trawalter, S., Axt, J., & Oliver, M. (2016). Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(16), 4296-4301. Retrieved March 4, 2021, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/26469319

Johnson, J. D. , Asiodu, I. V. , McKenzie, C. P. , Tucker, C. , Tully, K. P. , Bryant, K. , Verbiest, S. & Stuebe, A. M. (2019). Racial and Ethnic Inequities in Postpartum Pain Evaluation and Management. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 134(6), 1155–1162. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003505.

Kennel, Jamie, Withers, Elizabeth, Parsons, Nate & Woo, Hyeyoung. (2019). Racial/Ethnic disparities in pain treatment: Evidence from Oregon emergency medical services agencies. Medical Care, 57, 924-929. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000001208

North Carolina Healthcare Association Issues Statement on Racism as a Public Health Crisis. NCHA, 2020.

Featured Image Source:

Google Images, Creative Commons license