The memory of Roe v. Wade can be explored through its relation to anti-abortion and pro-life movements and organizations both before and in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 1973 decision to legalize abortion. The tactics and methods used by those opposed to abortion in the US, leading up to and after Roe v. Wade, can be understood largely as the connection of other sites of memory, often associated with cruelty and the violation of the sacrosanct, to the practice of abortion. In this manner, the use of other memories as vehicles of emotion, understanding, and ideas can be viewed as a means through which the religious right and anti-abortion activists constructed abortion as a moral wrong and contributed to how Roe v. Wade is widely imagined and remembered.

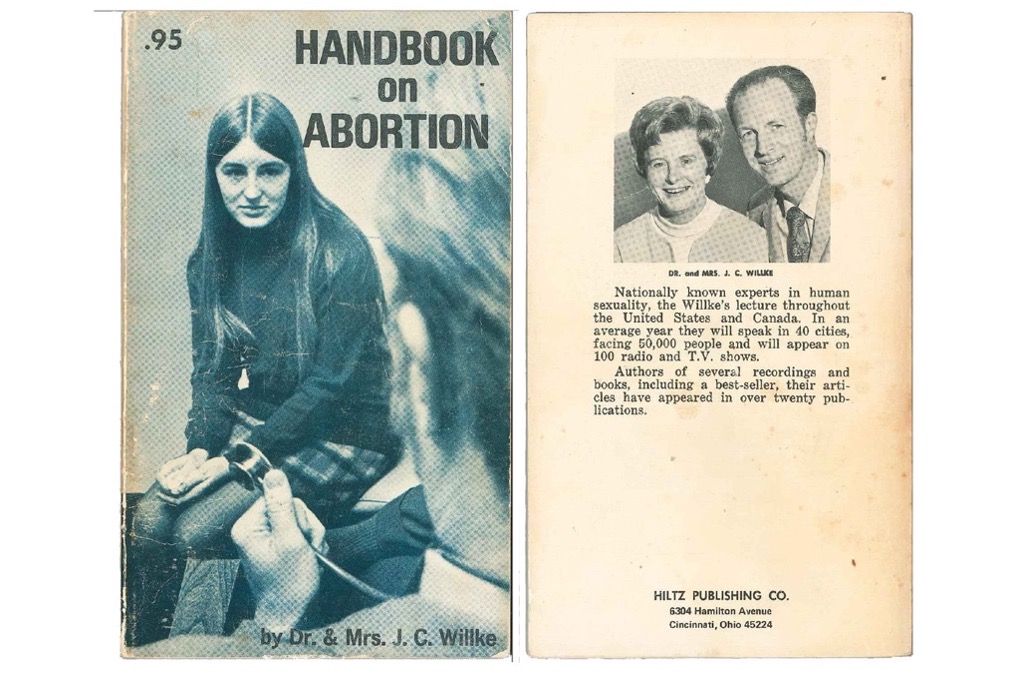

Before the Roe v. Wade decision was rendered by the Supreme Court in 1973, anti-abortion activists used the partial nature of collective memory to construct and emphasize abortion as infanticide to promote their cause. Jennifer Holland argues that before the Roe v. Wade decision was rendered, the anti-abortion movement did not have much of an explicit religious tone, as evidenced by the extreme popularity of the Handbook on Abortion, written by Catholic husband and wife John and Barbara Willke, in the pro-life movement at the time [1]. The Handbook contained graphic pictures of abortions and fetuses [1]. These depictions helped form the understanding of the “fetus, legally and culturally, as a baby” among many Americans [1]. In this manner, the partial nature of the collective memory of abortion, as communicated by these fetal representations, can be seen in the inclusion of images only amplifying the narrative of the “baby” at risk of being “murdered” rather than promoting discussions concerning the viability of the fetus. The idea of the not-yet-born baby as a victim of murder as well as representations of developing fetuses as babies, then, were likely employed by pro-life activists and groups in an attempt to craft the official hegemonic memory of abortion as an act of violence against the innocent.

More Images of Inside the Handbook (Graphic): https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2022/06/fetal-photos-jack-barbara-willke-handbook-on-abortion.html

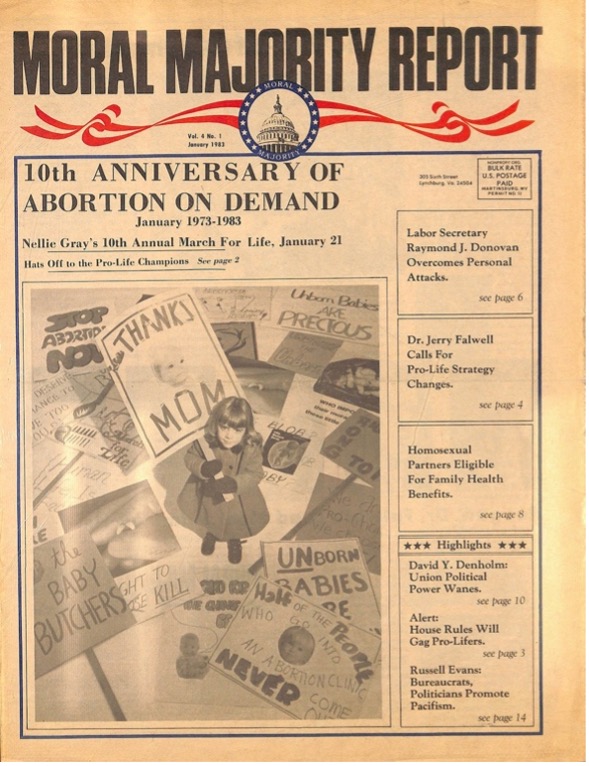

Moreover, after the Roe v. Wade decision was handed down by the Supreme Court, Roe and abortion itself in the US became a site of memory based on past memories of atrocities and suffering intertwined with ideas of family informed by conservative Christian ideology. Seth Dowland describes that Jerry Falwell, a Baptist preacher and the creator of the Moral Majority, a Christian activist group, declared the elimination of access to abortion as key in protecting and maintaining the American family [2]. The religious right also saw the family organization and gender roles they valued, informed by the Bible, as possible casualties of continued access to abortion [2]. This rhetoric likely reflects the mobilization of the particular and universal nature of collective memory to advance religiously motivated anti-abortion sentiment. Specifically, the idea of the family invoked by Falwell and the Christian right likely stirred up fear and anger among those concerned about the decay of the American family and, by extension, their own family through legal access to abortion. This may have helped create personal sites of abortion memory in families, furthering the anti-abortion cause. In addition, flyers printed and distributed by the Moral Majority described abortion as a “holocaust” and claimed similarities between Roe and the Dred Scott v. Sandford decision that reinforced the legality of slavery [2]. The use of the memory of the WWII Holocaust and American slavery by pro-life organizations illuminates the unpredictable nature of collective memory. Specifically, it shows how disparate historical events can be linked through their strong emotional power to contemporary issues like abortion in order to produce certain opinions and responses. The memories of human-caused tragedies and personal family decay, then, likely served as the frameworks through which the religious right sought Roe and abortion to be perceived in order to achieve the outlaw of abortion.

More Moral Majority Reports: https://daily.jstor.org/the-moral-majority-collection/

Furthermore, the religious right also manipulated the memory of contemporary and historical moments to shape how abortion and Roe v. Wade was understood and constructed in the American imagination. For example, Jerry Falwell specifically blamed the Roe decision handed down by the Supreme Court as the reason why abortion was taking place in the United States in the first place because he viewed the Supreme Court as a negative agent of liberal change [3]. This attribution by Falwell highlights the usable nature of collective memory. Particularly, since the practice of abortion was blamed on the Supreme Court’s Roe decision, the conservative right may have strategically used the collective memory of the decision to create a clear target for their political action and religious anxieties. Additionally, in 1980, a Christian rally called Washington For Jesus (WFJ), which promoted anti-abortion sentiment among other conservative ideas, was planned to be held on the date of the anniversary of the landing of English colonists at Jamestown [4]. This, again, illuminates the usable nature of collective memory. The conflation of anti-abortion sentiment with what many may consider the “birth” of the US fictitiously roots anti-abortion activism and ideas in the foundation of the US, giving pro-life and anti-abortion movements the perception of being legitimate and traditional. Therefore, the usable nature of collective memories, like the memory of the impacts of Roe, real or not, and the “birth” of the US, was likely key in forming the US perception of Roe v. Wade and abortion.

Anti-abortion activists and the religious right emphasized specific aspects of the collective memory of abortion to craft desired understandings and perceptions of Roe v. Wade and abortion itself. This practice highlights the significant influential power of connecting past and contemporary memories to issues like access to reproductive care in order to promote particular narratives and histories. Additionally, an examination of the ideas and memories evoked by anti-abortion activists both before and after Roe v. Wade was rendered in 1973 provides insight into the continuity that existed and the changes that took place in the promotion of the pro-life cause.

Emma Powell

Sources for Post

[1] Holland, Jennifer. “Abolishing Abortion: The History of the pro-Life Movement in America.” The American Historian. Organization of American Historians. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://www.oah.org/tah/issues/2016/november/abolishing-abortion-the-history-of-the-pro-life-movement-in-america/#fn8.

[2] Dowland, Seth. “‘Family Values’ and the Formation of a Christian Right Agenda.” Church History 78, no. 3 (2009): 606–31. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0009640709990448.

[3] Williams, Daniel K. “Jerry Falwell’s Sunbelt Politics: The Regional Origins of the Moral Majority.” Journal of Policy History 22, no. 2 (2010): 125–47. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0898030610000011.

[4] Williams, Daniel K. God’s Own Party: The Making of the Christian Right. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. https://books.google.je/books?id=lqf3KBaqgI8C&printsec=copyright#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Sources for Photos

[5] Wallenbrock, Emma. “The Photos That Jump-Started the pro-Life Movement.” Slate Magazine. Slate, June 8, 2022. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2022/06/fetal-photos-jack-barbara-willke-handbook-on-abortion.html.

[6] “The Moral Majority: Collection of Primary Sources .” Open Community Collections. JSTOR, July 1, 2022. https://daily.jstor.org/the-moral-majority-collection/.