The Riot Grrrl movement started small. The feminist punk rock movement started in Olympia Washington in the early 1990s as a starting point of creating space for women in punk music. Throughout the 90s the group grew into a large punk subculture across the US with notable artists such as Bikini Kill, Heavens to Betsy, and Bratmobile[3,4]. The three r’s in the word Grrrl evoke a guttural growl and replace the gentleness associated with the word “girl”[4]. The movement sought to overturn what they saw as patriarchal norms and empower women and the definition of Riot Grrrl quickly expanded beyond just music. Riot Grrrl groups published zines (small batch magazines), organized protests, and raised awareness about topics such as sexism, sexual violence, women’s identity, and abortion rights [4]. The culture faded in the early 2000s but has seen a recent resurgence in the late 2010s with the tightening of abortion restrictions and the reversal of Roe vs Wade [3].

The creation of Riot Grrrl culture coincided with the tightening of abortion restrictions in the US. In the 1992 Planned Parenthood of Pennsylvania vs Casey was a victory for abortion rights in Pennsylvania but set the precedent of “undue burden”. If a state’s restriction on abortion did not cause unnecessary obstacles to a person seeking an abortion before the fetus was viable, the restriction was legal[6]. Afterwards, several states passed laws restricting abortion access including parental notification laws and waiting periods. The presidency of George H.W. Bush from 1989-1993 encouraged abortion restriction and Bush sought to take down Roe vs Wade[1]. The Riot Grrrl response to threats on abortion rights and Roe vs Wade are found in the pro-choice protests they organized and attended, lyrics they wrote and zines the distributed.

One of the earliest Riot Grrrl abortion responses came in the song “Baby’s Gone” by Heavens to Betsy. The song is written from the perspective of a teenage girl who has died from an illegal abortion and highlights several aspects of the pro-choice position[5]. Most prominently, the song represents the position that restrictions on abortions only prevent safe abortions, and that abortion will still happen no matter the legality of it. The girl in the song “died on a knitting needle”[5] because she felt that she couldn’t seek help from her parents. This connects to another theme in the song which is shame around abortions and female sexuality. The Riot Grrrl movement sought to embrace female sexuality and dispel feelings of guilt that many felt with embracing their sexuality [3]. The first stanza of the song has the lines “I grew up with your rules and I know sex is what I shouldn’t do I know what I can’t tell you”[5]. The teenager has shame around sex because that’s what she’s been socialized to feel, and she also feels shame around telling her parents about getting an abortion. Abortion was a taboo subject in the 80s and 90s, not discussed freely in academic settings and the news as it is in today’s social climate. Riot Grrrl groups like Heavens to Betsy broke this taboo to advocate for women’s right to choose. The purpose of songs like “Baby’s Gone” was to express anger over the restrictions on abortion rights but also to start conversations about abortion and women’s rights[3]. The song also presents an alternate victim to the normal view of who abortion harms. Abortion restrictions are put in place to protect unborn babies, but the title of the song subverts this. The same restrictions and societal shame that were created to protect unborn babies have killed this family’s teenage daughter, their “baby”. The teenager says she’ll “be a little girl forever”[5] because this experience has deprived her of her opportunity to grow up.

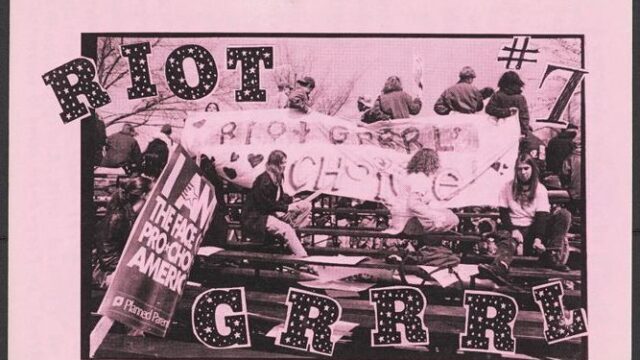

Riot Grrrl abortion activism also involved attending protests and publishing literature, often in zines. The band Bratmobile published a zine called “Riot Grrrl” that focused on promoting Riot Grrrl events and spreading feminist activism [2]. The 7th edition of the zine was published in 1992 after a pro-choice march in Washington on April 5th. The cover of the zine featured the banner that the Riot Grrrl group made that reads “Riot Grrrls © Choice!”[2]. The issue contains information about the march and what Riot Grrrl did at the march as well as personal stories, artwork, and a piece titled “I Won’t Go Back” written by a girl who was raised anti-abortion but changed her views as she grew up. The focus of the piece is on the girl’s shift from a pro-life to a pro-choice view, but the underlying theme of a need for bodily autonomy is what drove her shift in perspective[2]. She talks about a time after a sexual assault where she felt that “the rights to govern my own body”[2] were taken from her. She compares the restriction of abortion access to her own assault because by her rationale, both are a man exercising control over a woman’s body and taking away her autonomy [2]. Riot Grrrl gave women spaces to have control and be informed in their own decisions, and the publishing of this article connects the overarching view of Riot Grrrl culture on freedom and autonomy as one of the main motivations for their support of abortion rights.

Citations

- National Archives and Records Administration. (n.d.). National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved April 20, 2023, from https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/infocus/achievement/chap15.html

2. Neuman, M., & Wolfe, A. (1992, April). Riot Grrrl, (7). Retrieved April 19, 2023, from https://digdc.dclibrary.org/islandora/object/dcplislandora%3A38110?solr_nav%5Bid%5D=a801cbb8dd3516a32bad&solr_nav%5Bpage%5D=1&solr_nav%5Boffset%5D=0#page/3/mode/1up

3. Perry, L. (2015). I can sell my body if I wanna: Riot grrrl body writing and performing shameless feminist resistance. Lateral, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.25158/l4.1.3

4. Rosenberg, J., & Garofalo, G. (1998). Riot grrrl: Revolutions from within. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 23(3), 809–841. https://doi.org/10.1086/495289

5. Sawyer, T., & Tucker, C. (1992) Baby’s Gone. [Recorded by Heavens to Betsy]. On Heavens to Betsy. K Records

6. Shivaram, D. (2022, May 6). Roe established abortion rights. 20 years later, Casey paved the way for restrictions. NPR. Retrieved April 25, 2023, from https://www.npr.org/2022/05/06/1096885897/roe-established-abortion-rights-20-years-later-casey-paved-the-way-for-restricti

I enjoyed your thoughtful research surrounding Riot Grrrl. Centering your site of memory around one particular song was an effective way to communicate how the memory of abortion access is preserved in cultural media. However, I would be interested in further research not just on what Riot Grrrl presented but HOW it was received/perceived. Particularly, do you think it is a uniquely American freedom of speech that would allow counter-cultural voices to be heard in this way? And how was the general population actually influenced by their message?

I didn’t know how big of an impact zine culture had on the pro-choice movement within the punk genre of the 90’s. I’d love to see some of those zines, if they still exist somewhere! Regardless, I think music is one of the perfect vessels for the spread of this movement, especially for story telling purposes that catch an audiences’ attention. Even if one isn’t paying attention to the lyrics, which is hard to do when listening to punk music, those messages are surely subliminally available in the listener’s mind somewhere. The memory of the story told through this song seems to be an emergent form of memory, a new and never seen before version of the story of women who die trying to get an abortion under unsafe circumstances. This is what makes it so novel and attractive to those listeners in both the subculture and the general populous who hear the song on the offhand. There’s also this notion of a material memory through the punk zines that were made in pursuits of a different form of education. All of these different forms of memory come together in the punk movement to form a very unique and interesting combination of memory that forces the people to remember these stories and perspectives. The graphic and forcefulness of the punk subculture is one of the most ideal places for a very controversial topic like this to grow and take up roots in memory, I think.

I really liked your discussion about the song “Baby’s Gone” by Heavens to Betsy. I feel like the memory of the teenage girl dying from a botched abortion serves as a vernacular memory challenging the official hegemonic memory of abortion which places the fetus or “baby” as the ultimate victim. I wonder if the memory of the teenage girl as a victim worth protecting and advocating for could tap into the processual nature of collective memory, allowing for more and more people to remember and perceive abortion restrictions as not simply a matter of “saving lives” as more narratives of the impacts of botched and restricted abortions are emphasized. Furthermore, I feel like the memory of the teenage girl dying from a botched abortion may help change individuals’ perceptions of those getting abortions. This may be accomplished by highlighting how women and girls getting abortions are often vulnerable and/or young rather than callous “baby murderers” who refuse to face the consequences of their sexual “indiscretions.”

I really enjoyed your article! I had no previous knowledge of the Riot Grrrl movement, but the group is very intriguing. I think that the way you centered the paper around the song “Baby’s Gone” was an excellent way to highlight the memory aspect of the article. The songs from this movement, and music in general, can become a form of living memory and it seems this was the case with their music. The Riot Grrrl movement is intriguing from a memory perspective because, between the Zines and music created by many people, the movement has created its own collective memory. I would be curious to know how this resurgence in the movement differs from the original version.

I really enjoyed the article you wrote. When we look back on historical moments and movements I think we often overlook art like this as a valuable tool. I think it is great that you provided us with context for the movement by detailing what “Baby’s Gone” meant to the movement. I would be fascinated to know how this movement has impacted other subcultures we see in the modern world. The image you included ties in perfectly as you discuss the meaning behind the inclusion of the three R’s in the world girl. I think it would have been beneficial as well to include an image of a page of one of the zines that you mention to demonstrate the material memory that seems to be so important to the movement. I imagine that movements like the Riot Grrl movement have influenced everything from feminist literature and theory to the continued push for acceptance of Female artists in male-dominated genres.

This is such a powerful exmaple of how abortion debates extend beyond politcs and court cases and have a real impact of cultural memory. The anger and fear young women feel at having their rights attacked, as well as the reinforcement of partiarchal inequalities is expressed in this “punk rock” response. It seems likely that a similar cultural response, or a different form of retaliation carrying the same sentiment will begin to grow following the Dobbs decision.

YES! Thanks for deciding to do this topic–you found a specific niche in collective memory and brought it to light beautifully. By walking the reader through some of the song lyrics and the scope of Riot Grrls’ actions, you help us understand the importance of Riot Girls to collective memory.

There are many interesting facets of this article but the one relating to “Baby’s Gone” is the one I find most interesting. I did not know that there was a band named Heaven’s to Betsy. I also did not ever think that such a southern vernacularism would show up in Washington. Perhaps using southern slang was a way to poke fun at the historically conservative south and their views on abortion. I also did some research and many zines are being replicated today and there are some original ones for sale as well. I find primary sources like that to be interesting.