Very little is simple, straightforward, and not nuanced about the abortion debate in America. Even the most straightforward aspects have a complicated story. Based on the debate happening today, one most likely expects that the debate was always centered on abortion. However, when Roe v. Wade was decided on January 22, 1973 in favor of Jane Roe, privacy of citizens was the central concern of the justices. Justice Harry A. Blackmun wrote the majority decision on Roe representing the opinions of Warren Earl Burger, William Orville Douglas, William Joseph Brennan, Jr., Potter Stewart, Thurgood Marshall, and Lewis Franklin Powell, Jr. [1] The opinion relied on previous judicial decisions to determine a fundamental right to privacy, but also determined that this right was not absolute.

Nothing stands on its own, especially Supreme Court decisions. As background for further discussion the opinion examined laws and views concerning abortion in Roman, English, and Early American law as well as the history of abortions. The reason for observing this history is so the court can have the background when addressing the appellant’s claim that Texas’s statutes violate their right to personal liberty. [1] The opinion says this right is “embodied in the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause; or in … the Bill of Rights or its penumbras …; or among those rights reserved to the people by the Ninth Amendment.” [1, p.129] The right to personal liberty supposedly specified in these areas of the Constitution became the focus of the debate and the opinion in Roe v. Wade. The opinion introduces this constitutional right to privacy saying it is found within the preceding areas of the Constitution and uses the earlier decisions of Union Pacific R. Co. v. Botsford, Stanley v. Georgia, Terry v. Ohio, Katz v. United States, Boyd v. United States, Griswold v. Connecticut, Meyer v. Nebraska, and Palko v. Connecticut as justification. [1, p.152] Importantly Blackmun noted, “This right of privacy … is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.” [1, p.153] Subsequently the opinion lists several ways in which denying a woman the choice to have an abortion would cause harm, and even calls this harm “apparent.” However, the court did not agree with the appellant’s claim that the woman’s right is absolute. They noted that, “a State may properly assert important interests in safeguarding health, in maintaining medical standards, and in protecting potential life.” [1, p.154]

The appellee argued that a fetus is a person and therefore their rights must be protected as well. However, they also noted that no case could be cited that supports this view. Since every use of the word “person” in the Constitution only is applicable postnatally, the court concluded a fetus is not a person. However, they held that the state does have an interest at a certain point in development. In the discussion of what point state interest becomes important, the court considers many outside perspectives on when life begins. Important to the current abortion debate, the court even acknowledged the Catholic ensoulment theory that holds that life begins at conception. Even still, the law had never viewed the unborn as a whole person and so the court rejected that Texas could override a woman’s rights. [1, p.162] Since neither a woman’s right to privacy and abortion nor the State’s right to impose itself are absolute, a balance between the two must be reached. This compromise came in the form of a trimester approach to rights and legislation. The opinion states that during the first trimester all decisions must be left to the mother and her physician. During the second trimester the State may regulate abortion related to the health of the mother. And finally, during the third trimester the State may regulate or ban abortion, unless the health of the mother is in jeopardy. This trimester framework served to balance the rights and interests of all those involved. The Texas law at question in Roe was in contradiction with this new framework and so the court ruled it unconstitutional and sided with Roe.

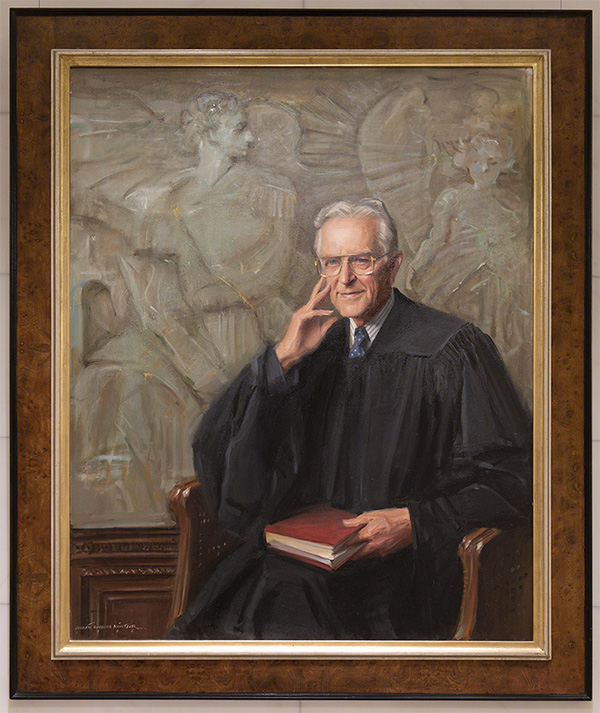

Several years after the decision of Row v. Wade, Justice Blackmun sat down for an interview with Bill Moyers and reflected on his time in the court and Roe. Blackmun had been appointed to the Supreme Court unanimously as a supposed conservative justice. In the interview, Blackmun rejected that he was a conservative justice saying, “the round peg doesn’t fit into the square hole.” [4] On several occasions, including Roe, he decided against the conservative ideology while on the court. Blackmun said, “I’m not so sure that I have a judicial, constitutional ideology, at all. To me, every case involves people. … If we forget the humanity of the litigants before us that we’re in trouble … No matter how great our supposed legal philosophy can be.” [4] This is certainly reflected in his opinion on Roe v. Wade. One thing that is hardly mentioned in his majority opinion are political views. Instead, he wrote about, and based his decision on, the wording in the Constitution, prior judicial decisions, and most importantly the effect of certain outcomes on those at interest. This more impartial approach made his decision stand up to scrutiny more resiliently, and defended him, a bit, from attacks on his character. Of course, he was still attacked. On such a controversial case no result would have made everyone happy. By removing himself from political turmoil and focusing on citizen’s humanity, he gave himself more of a leg to stand on when constructing this opinion.

The way in which we remember Blackmun’s opinion will continuously change. At the time of the decision, it did not widely register as a monumental decision. One pro-Roe woman said, “I did not really register how impactful Roe was [at the time],” and an anti-abortion woman mentioned, “It was just a nonissue for me.” [2] However even by the time Blackmun had his interview with Moyers, debate and controversy around Roe had grown to the point that Moyers asked Blackmun if he thought Roe would be overturned. Blackmun responded, “I think any case up here always stands a chance of being overturned. … That will depend primarily on the personnel of the Court. … But it has stood for fourteen years, now. I think it is a landmark decision along the road that we must take toward the emancipation of women.” [4] Of course, now it has been overruled by a 5-4 decision in Dobbs v. Jackson. The current impact of Roe is solely its cultural memory since it has been overturned. Yet despite that fact, 50 years later it feels that we discuss the opinion more now than we ever did when it was decided. So long as abortion is a dividing issue in America, Blackmun’s words will be important, debated, and remembered by Americans.

-Will Scurria

Works Cited

[1] Blackmun, Harry A, and Supreme Court Of The United States. U.S. Reports: Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113. 1972. Periodical. https://www.loc.gov/item/usrep410113/.

[2] Branigin, Anne. “Coming of Age during Roe v. Wade: Women Tell Us How They Saw the Moment Then and Now.” The Washington Post. WP Company, May 3, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/2022/01/21/womens-memories-roe-decision-1973/.

[3] Justice-Blackmun-Harry-A-1970-1994. Photograph. Supreme Court Historical Society. Washington, D.C. SUPREME COURT HISTORICAL SOCIETY. Accessed April 13, 2023. https://supremecourthistory.org/associate-justices/harry-a-blackmun-1970-1994/.

[4] Moyers, Bill, and Harry A. Blackmun. Mr. Justice Blackmun. Other. Moyers. Doctoroff Media Group LLC, March 30, 2015. https://billmoyers.com/content/mr-justice-blackmun-supreme-court/. Conducted 16 April 1987