The Riot Grrrl movement started small. The feminist punk rock movement started in Olympia Washington in the early 1990s as a starting point of creating space for women in punk music. Throughout the 90s the group grew into a large punk subculture across the US with notable artists such as Bikini Kill, Heavens to Betsy, and Bratmobile[3,4]. The three r’s in the word Grrrl evoke a guttural growl and replace the gentleness associated with the word “girl”[4]. The movement sought to overturn what they saw as patriarchal norms and empower women and the definition of Riot Grrrl quickly expanded beyond just music. Riot Grrrl groups published zines (small batch magazines), organized protests, and raised awareness about topics such as sexism, sexual violence, women’s identity, and abortion rights [4]. The culture faded in the early 2000s but has seen a recent resurgence in the late 2010s with the tightening of abortion restrictions and the reversal of Roe vs Wade [3].

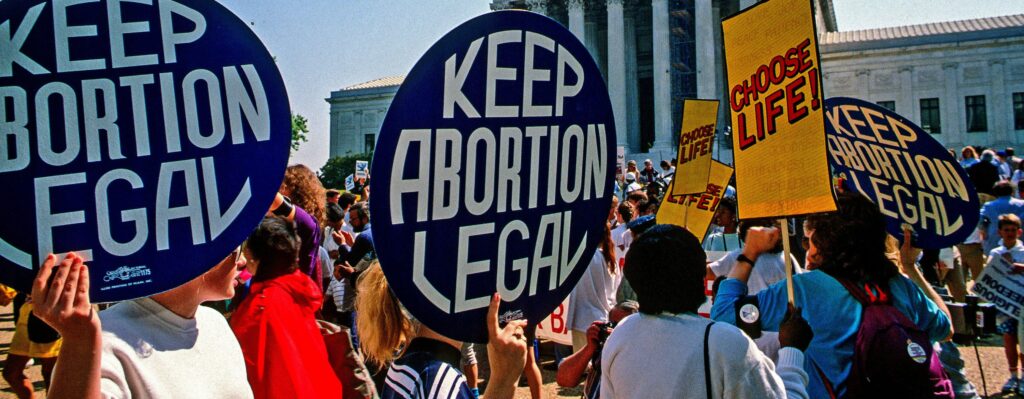

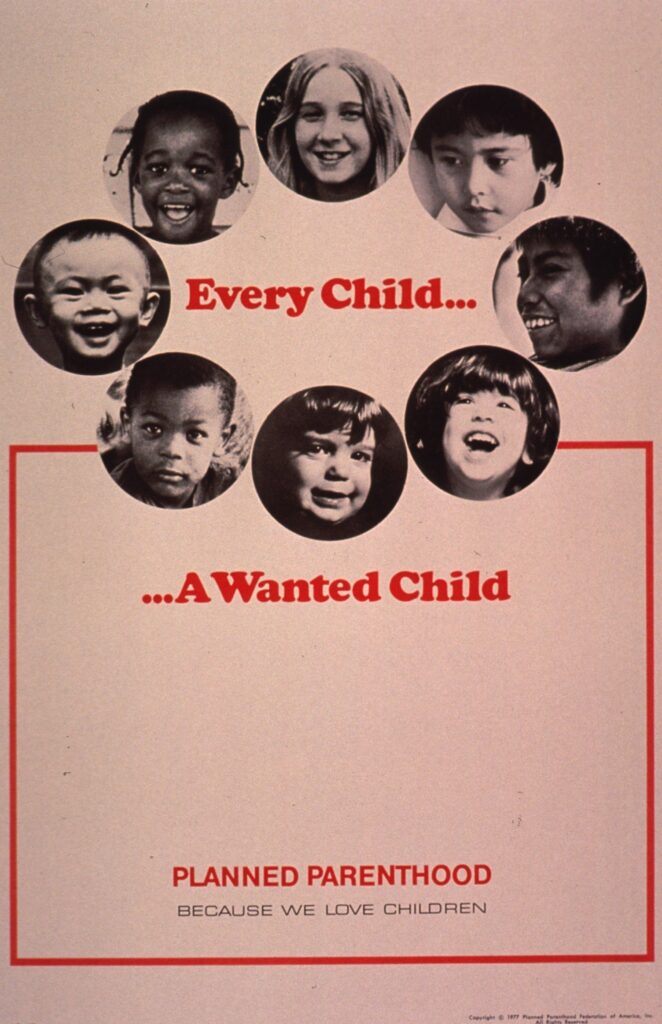

The creation of Riot Grrrl culture coincided with the tightening of abortion restrictions in the US. In the 1992 Planned Parenthood of Pennsylvania vs Casey was a victory for abortion rights in Pennsylvania but set the precedent of “undue burden”. If a state’s restriction on abortion did not cause unnecessary obstacles to a person seeking an abortion before the fetus was viable, the restriction was legal[6]. Afterwards, several states passed laws restricting abortion access including parental notification laws and waiting periods. The presidency of George H.W. Bush from 1989-1993 encouraged abortion restriction and Bush sought to take down Roe vs Wade[1]. The Riot Grrrl response to threats on abortion rights and Roe vs Wade are found in the pro-choice protests they organized and attended, lyrics they wrote and zines the distributed.

One of the earliest Riot Grrrl abortion responses came in the song “Baby’s Gone” by Heavens to Betsy. The song is written from the perspective of a teenage girl who has died from an illegal abortion and highlights several aspects of the pro-choice position[5]. Most prominently, the song represents the position that restrictions on abortions only prevent safe abortions, and that abortion will still happen no matter the legality of it. The girl in the song “died on a knitting needle”[5] because she felt that she couldn’t seek help from her parents. This connects to another theme in the song which is shame around abortions and female sexuality. The Riot Grrrl movement sought to embrace female sexuality and dispel feelings of guilt that many felt with embracing their sexuality [3]. The first stanza of the song has the lines “I grew up with your rules and I know sex is what I shouldn’t do I know what I can’t tell you”[5]. The teenager has shame around sex because that’s what she’s been socialized to feel, and she also feels shame around telling her parents about getting an abortion. Abortion was a taboo subject in the 80s and 90s, not discussed freely in academic settings and the news as it is in today’s social climate. Riot Grrrl groups like Heavens to Betsy broke this taboo to advocate for women’s right to choose. The purpose of songs like “Baby’s Gone” was to express anger over the restrictions on abortion rights but also to start conversations about abortion and women’s rights[3]. The song also presents an alternate victim to the normal view of who abortion harms. Abortion restrictions are put in place to protect unborn babies, but the title of the song subverts this. The same restrictions and societal shame that were created to protect unborn babies have killed this family’s teenage daughter, their “baby”. The teenager says she’ll “be a little girl forever”[5] because this experience has deprived her of her opportunity to grow up.

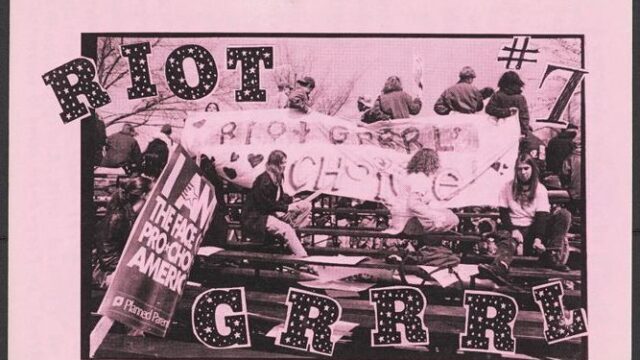

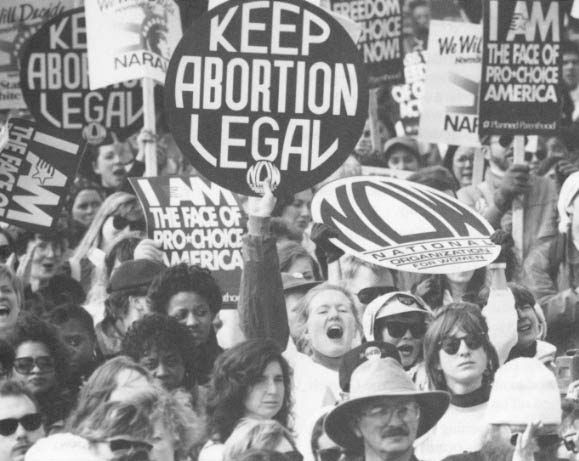

Riot Grrrl abortion activism also involved attending protests and publishing literature, often in zines. The band Bratmobile published a zine called “Riot Grrrl” that focused on promoting Riot Grrrl events and spreading feminist activism [2]. The 7th edition of the zine was published in 1992 after a pro-choice march in Washington on April 5th. The cover of the zine featured the banner that the Riot Grrrl group made that reads “Riot Grrrls © Choice!”[2]. The issue contains information about the march and what Riot Grrrl did at the march as well as personal stories, artwork, and a piece titled “I Won’t Go Back” written by a girl who was raised anti-abortion but changed her views as she grew up. The focus of the piece is on the girl’s shift from a pro-life to a pro-choice view, but the underlying theme of a need for bodily autonomy is what drove her shift in perspective[2]. She talks about a time after a sexual assault where she felt that “the rights to govern my own body”[2] were taken from her. She compares the restriction of abortion access to her own assault because by her rationale, both are a man exercising control over a woman’s body and taking away her autonomy [2]. Riot Grrrl gave women spaces to have control and be informed in their own decisions, and the publishing of this article connects the overarching view of Riot Grrrl culture on freedom and autonomy as one of the main motivations for their support of abortion rights.

Citations

- National Archives and Records Administration. (n.d.). National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved April 20, 2023, from https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/infocus/achievement/chap15.html

2. Neuman, M., & Wolfe, A. (1992, April). Riot Grrrl, (7). Retrieved April 19, 2023, from https://digdc.dclibrary.org/islandora/object/dcplislandora%3A38110?solr_nav%5Bid%5D=a801cbb8dd3516a32bad&solr_nav%5Bpage%5D=1&solr_nav%5Boffset%5D=0#page/3/mode/1up

3. Perry, L. (2015). I can sell my body if I wanna: Riot grrrl body writing and performing shameless feminist resistance. Lateral, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.25158/l4.1.3

4. Rosenberg, J., & Garofalo, G. (1998). Riot grrrl: Revolutions from within. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 23(3), 809–841. https://doi.org/10.1086/495289

5. Sawyer, T., & Tucker, C. (1992) Baby’s Gone. [Recorded by Heavens to Betsy]. On Heavens to Betsy. K Records

6. Shivaram, D. (2022, May 6). Roe established abortion rights. 20 years later, Casey paved the way for restrictions. NPR. Retrieved April 25, 2023, from https://www.npr.org/2022/05/06/1096885897/roe-established-abortion-rights-20-years-later-casey-paved-the-way-for-restricti