Juliana Spector

I have been struggling to find the right words that encapsulate what my experience on the Migrant Health Service-Learning Trip was. Prior to attending this trip, I had very limited knowledge about what we were going to experience; and I feel thankful that this was the case. However, I did know this. I knew that I had a special place in my heart for public health work related to migrants/asylum seekers. My mom was born in Mexico and immigrated here with my grandmother when she was still a baby. While her experience was very different than the ones, I knew we were going to encounter, I felt a pull and almost a duty to my culture to go on this trip and assist and learn as much as I can. At first, I was a little nervous that I missed out on the class portion of this experience. The people going on this trip all knew each other and potentially bonded during the class, where I was pretty much meeting everyone for the first time (to have a real conversation) when we arrived at the airport. I was not nervous that I was not going to get along with the people on the trip, I was nervous that they might have more knowledge in this area because they all had the experience of the class. While I do think the class would have been beneficial beforehand, I felt extremely lucky that the people on this trip were open to sharing what they learned and welcoming me with open arms.

As I think back to the first day we arrived in Arizona, I wanted to share a piece of writing I journaled before the first day volunteering at Casa Alitas, “I think you just have to go into tomorrow with an open mind, heart, and spirit to learn from others and surrender yourself to being uncomfortable. Try to find the peace, try to find the good, just try”. Despite writing that at the beginning of the experience, I think these words summarize a lot of what we were to experience each day in Arizona.

I spent the majority of my time at Casa Alitas volunteering at the Drexel location. I do not think I will ever forget us sitting in the break room on the first day when we just arrived and seeing the border patrol bus drop off migrants in what looked like a prison van for criminals. It’s feels terrifying to imagine the other spots along the border that do not have an organization like Casa Alitas. I think the biggest thing I felt when working the Tienda and food service areas was the lack of autonomy it felt like the people we were serving had. Almost all their choices were dictated by the rules we were to follow to help as many people as we can, the best we can, given the circumstances. It is an uncomfortable feeling to know only a sliver of what these people are going through yet having the privilege and power to be one making the majority of their choices. Even the aspect of wearing the mask for health precautions, it felt odd to hide part of our face when we see the vulnerability of the people we are looking at. However, in these situations, the best thing you can do, and I felt like the group did a good job of, was working our best to do it with a smile, a sense of compassion, and give it our all. Understanding our positionality is often talked about in the public health space. It is important to understand where we come from and where we sit in our space, before trying to insert ourselves in others space. The experience at Casa Alitas felt like a living example of this mentality.

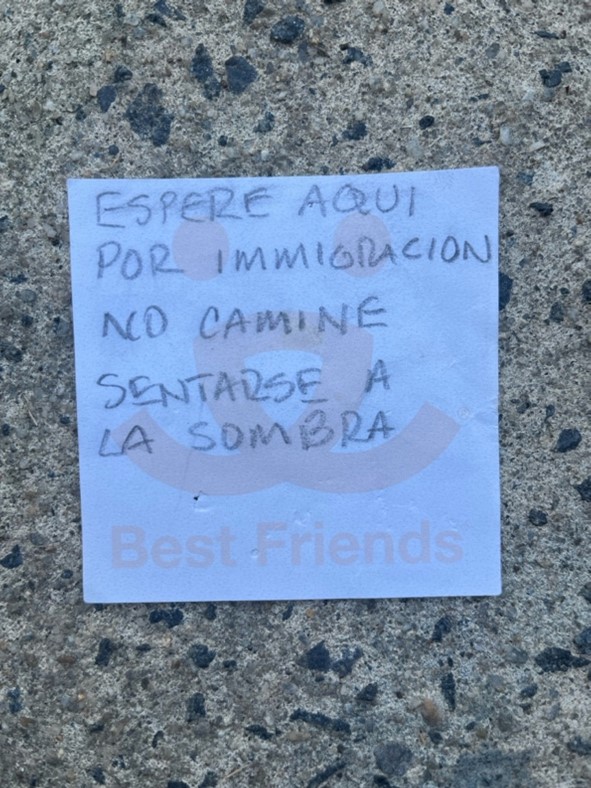

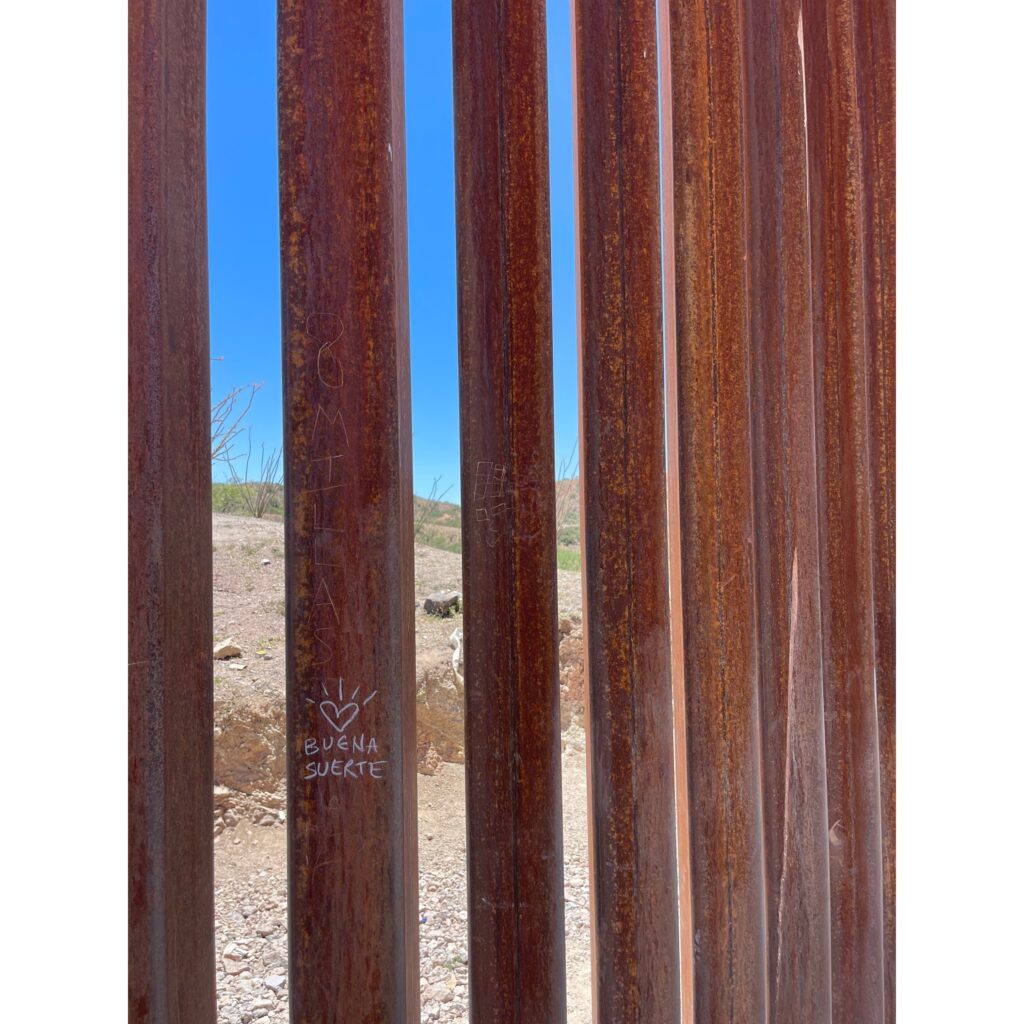

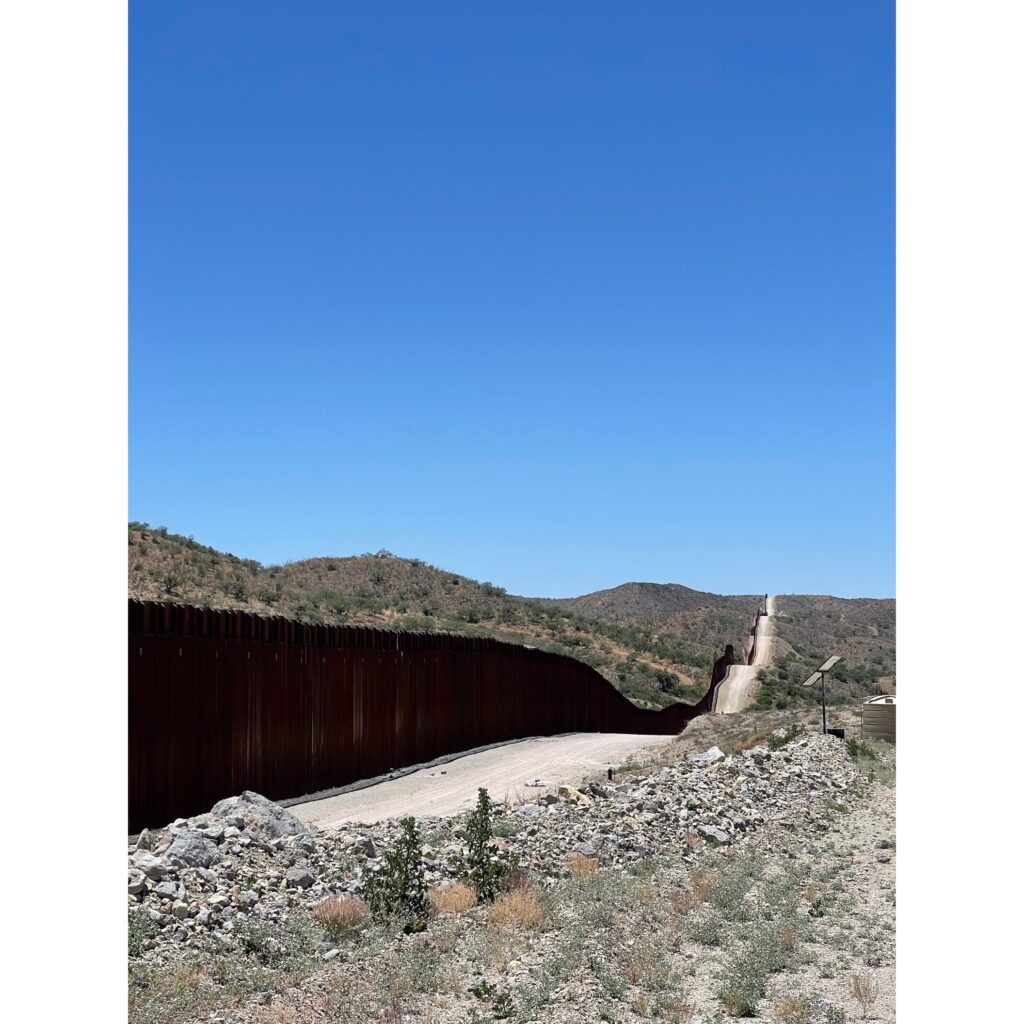

The day that impacted me the most though, was our experience at the Wall. While I already had the belief that this day would be the most impactful, I was not prepared to feel the way I felt when seeing it with my own eyes for the first time. I believe my first reaction was just shaking my head, trying to wrap my brain around and process what I was really looking at. The emotions that followed were a mix of anger, confusion, a little bit of humor from disbelief, and overwhelming sadness that this what our country is responsible for. Whether it was the extremely rough terrain we went through just to get to the town of Sasabe, to the almost mentally insane “road” we drove on along the wall, to the dangerous temperatures of the desert, everything about this Wall made no sense to me. The part that upsets me the most though is that no one really knows what happens at the border, unless you are there yourself. The idea that the media only portrays what they want to you think when you talk about migration. The overwhelming characterization towards all migrants being drug dealers, stealing jobs, or just illegal and unwanted. A pure hatred towards people they don’t even know, just because they are on the other side of the wall and come from a background different than people born in America.

I have been thinking a lot of what the word safe means. America built a wall to keep us safe; to protect us from the evils that might be brought into our country. However, the evil already exists, it’s among us. I know this because I felt it. After building the shelter, myself, Laura, and Jenny walked up along the wall away from the camp and towards the dead end. It was soon going to approach 2pm, the time border patrol is scheduled to drive over and pick up migrants. As we walked around, I slowly found myself being more anxious of the time. I could feel the uneasiness of thinking that the cartel was on the other side of the wall watching us. I thought, border patrol is coming, and my identification is back at camp, should I go back? I was embarrassed by my own fear. If this is what I was feeling as an American citizen, I cannot even fathom what the migrants crossing are feeling. How is the Wall keeping anyone safe? It isn’t. With the highest form of prevention through deterrence, all the Wall symbolizes is a form of power and dehumanization. It is a stunt mechanism to gain political favoritism rather than addressing the true needs of our country from individuals of governmental power. And the more you look at the Wall, the more you realize that landscape that surrounds it really is quite beautiful and peaceful. It represents another pure form of land that is destroyed by humans.

It is easy to be cynical and write a whole essay on the various disheartening things we experienced from the medical examiner to the water drops, to more time at Casa Alitas, but it would be a disservice to not mention the beautiful community that we witnessed from the non-profit organizations in Tucson. With the majority of them being retired, it was inspiring to see a glimpse of the humanitarian work they do in their local community to support and limit the amount of migrant related deaths. It helped restore a bit of faith in humanity that there are good people out there in the world that not just want to help others for the sake of helping, but welcome, accept, and connect with other humans.

Lastly, I want to highlight what I observed from the migrants we were serving. The most important detail we fail to hear about is the resiliency of the migrants that cross everyday. Whole families, families that were separated, young children, developing adolescents, the elderly, the disabled, pregnant women, single men, the list goes on for the types of individuals that exhibit the upmost strength to leave their homes behind and embark on the migration journey. Where we may not know their background, but we hope to guide them in their future, the humans we connected with illustrated the upmost gratitude, compassion, and sometimes even humor with us. It was one of the purest forms of humanity I have witnessed.

The more I think about this experience, the more gratitude I feel for being able to have it. It truly has changed my life and the way I view public health. It was the ultimate display of local being global and global being local, the power of connecting with a community in a culturally humble way and surrendering yourself to learning from the people around you to build trust. With new migration policies emerging as soon as we returned, I also feel gratitude towards the amazing group of people I spent time on this trip with. It is rare to find such passionate individuals that have such similar work ethic and mindsets towards approaching everyday with our all, despite being overwhelmed with thoughts, emotions, and tiredness from the days before. To our group leaders, it was inspiring to see our UNC faculty and professionals work alongside the students and connect with us in a way that also can feel rare when working with professors. Since returning, I already have bought many books on migrant related issues and hope to continue the ongoing learning process that is public health. However, if one thing has been learned, it definitely is that I feel a calling towards the humanitarian space and this experience solidified my passion for humanitarian work. I will take this trip with me for the rest of my life both inside and out of my career and I hope to share what I learned for many people to come.

Juliana