« À la prochaine » is a French colloquialism meaning “until the next time” or “till we meet again.” I intentionally used this phrase when saying goodbye to my family members, work colleagues, and fellow hostel guests because it felt like putting a semi-colon instead of a period to the end of my mission.

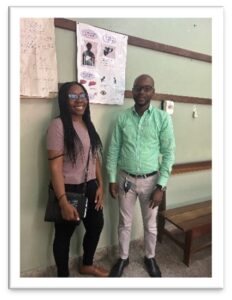

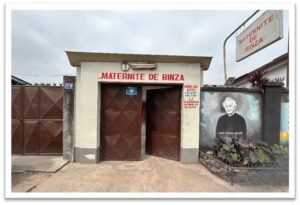

I was reluctant to give a conclusive goodbye because I knew I would find myself in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) once again. I hope to hold the aging hands of my precious grandparents once more, fill my plate with my aunt’s incomparable sweet plantains, and venture to other regions of the country including the magnificent waterfalls of Zongo Falls. I also hope to continue serving the DRC by supporting and leading efforts to strengthen public health capacity. Spending 5 weeks working alongside a hard-working team dedicated to minimizing infectious disease transmission, and consequently improving the nation’s public health, I have a more realistic perception of what a career in Global Health may look like for me.

This trip reaffirmed that I have a strong interest in improving inequities in health outcomes. I want to carry out this work by partnering with communities most impacted by public health inequities while cultivating and equipping leaders who are well-acquainted with the needs of their communities.

Not surprisingly, on the plane home, I found myself rewatching the 2018 Marvel film starring the late Chadwick Boseman, Black Panther. This film depicted the fictional African nation of Wakanda, which evaded the detrimental effects of colonialism and exploitation, allowing Wakandans to preserve their rich resources and thrive with technological innovations unbeknownst to the rest of the world. I didn’t realize how much satisfaction it brought me to see an African nation unhindered by a colonialist past, prospering from its abundant resources and ruled by a just leadership. I questioned why we accept inadequate healthcare and education access, violent conflict, poor governance, and pervasive poverty as an indefinite norm for any nation, and what would propel change.

This reflection fueled my desire to learn from and walk alongside people challenging the status quo, such as Dr. Chérie Rivers Ndaliko, a UNC professor who carries out work in eastern DRC within high-conflict zones to empower Congolese students to tell their own stories and advocate for change through artistic expression. Similarly, conversations with my brilliant colleague inspired me, who dreamed of opening his own business in the DRC but faced funding limitations and was discouraged by the lack of Congolese-produced goods. I gained hope from a new acquaintance from Burkina Faso who spent many years working with a local organization supporting peacebuilding efforts in the eastern DRC and is pursuing a degree in strategic peacebuilding and conflict transformation, refusing to accept what has become the norm and believing in the possibility for change. This hope extends to the young football players in front of my grandma’s house kicking up sand in an intense match among neighbors, perhaps a few may ascend to the world stage.

As I enter the final year of my master’s program, I am motivated to continue embracing discomfort and confronting complex challenges to redefine what’s considered normal. À la prochaine, DRC.

Nefer