Doctor, Lawyer, or Engineer – choose one (or more)

Growing up in a Habesha (Ethiopian) household, my family instructed me to take my studies seriously and rested their hopes to be financially free in this country they immigrated to on me. Even my Grandmother would hold me as a baby, saying, “Abiye, you are going to be a great doctor!” But happiness comes from being true to oneself – discovering who God wants me to be in life led me to explore advocacy, government, energy, marine biology, naval sciences, etc. I still gave medicine a shot by volunteering in the ED of Sentara (local hospital), but even as a pre-med first-year, I wasn’t set on medicine until this series of Operating Room Observations.

I learned a lot, and this is the day-by-day breakdown. Spoiler alert: This is naturally non-comprehensive as I was constantly learning and came from a place with little experience/understanding of operating rooms.

Monday

Included in my other article titled “NIH & CNH First Impressions”

Tuesday

Zooming on I-95, I listen to classic Black Gospel songs while heading to my 6:30 am class with the residents. When I get to DC the roads are a maze, but I still find the parking spot I’d discovered on Monday. With my scrubs in my backpack, I leave to enter CNH and find their classroom – only one issue: I don’t know where it is! The directions in my email were to get to the OR, so I wander the halls, and a nurse I ask directs me to the Anesthesiology fellow’s office (I had no clear image of what a fellow was). There, I meet Jacob Adams, the CNH anesthesiology fellow; he leads me to the small conference room filled with eight learners adorned with scrubs, their attention on…

Phones? The teacher who quickly acknowledged my addition at the table was giving the weary-eyed residents (I later found out half are anesthesiology assistants (AA)) a lecture about writing a meaningful personal statement that addresses why the residency they apply to interests them. This Black woman (the only other Black person) at the end of the table is the only other note-taker, and the rest are at various stages of attention. He ends the lecture with a few notes on how to quickly assess a patient with cardiac conditions and systemic and pulmonary ventricle workload and afterloads, and most of the residents/AAs leave, though one warmly asks me who I am. Looking at the time, I realize it’s 7! I realize I should’ve worn my scrubs from the start, then go to the bathroom to change for the OR.

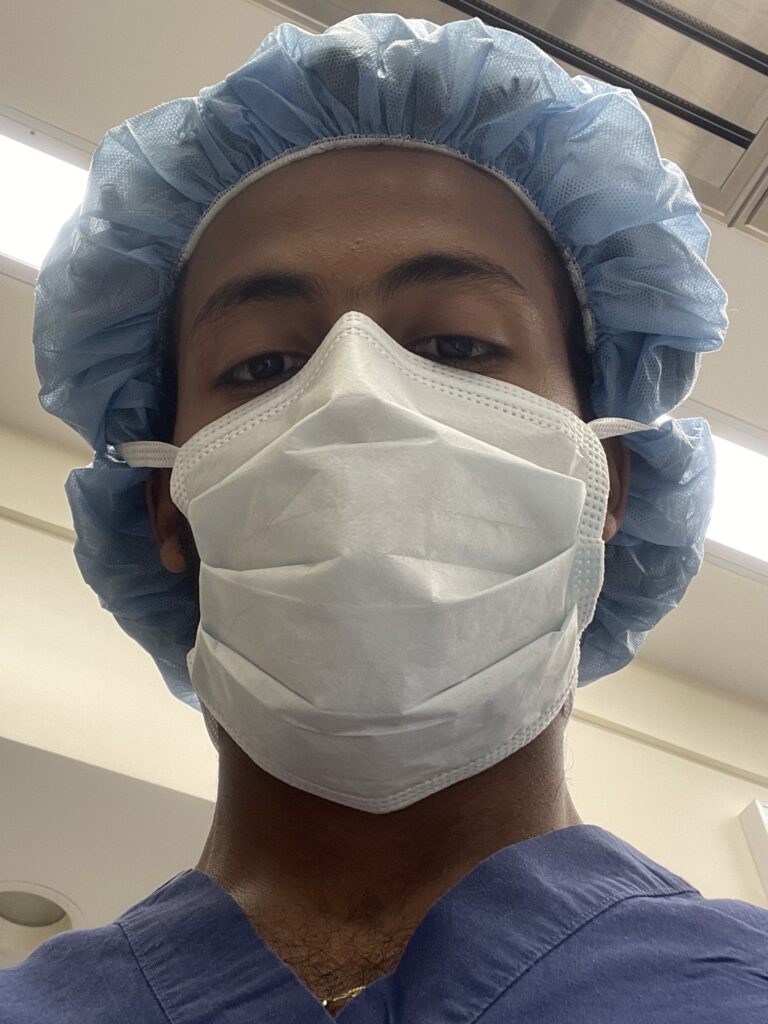

As I entered OR 8 (I left my backpack outside), another person in scrubs who was also entering stopped me and showed me how to properly put on a surgical mask. I go in asking for Dr. Esra, and the scrub tech, Adrian, tells me that the very same person I walked in was whom I’d be shadowing! With the whole room prepared, she immediately tells me to tag along to the holding rooms and greet our first patient with her and the OR nurse. I see her interact with this 3-year-old with subclinical seizures (phenotypically invisible), and understand the appeal of pediatrics – as “low-paying” as it might be. She straps the kid in a pink car to the OR, where they take them out crying and give them anesthesia before hooking up IVs and sticking needles in their arms. I go around the OR talking to the unoccupied participants (Dr. Esra was focused) and particularly enjoy talking to Nathan, the scrub/surgery tech who’d been there 11 years by accident. He was very particular about my staying 1 foot away from any surface covered in surgical blue, which is probably why Dr. Oluigbo respected him so much.

The group of neurosurgeons assigned this is uncharacteristically diverse – Nigerian immigrant attending, International Chinese fellow, White American resident – and only came in when everything in the scene was prepared for them. Nathan helps them suit up and fully sanitize the kid’s head in preparation for them to insert 12 wires for magnetic CT scans to locate where her seizures originated. The scene isn’t too bloody, though I get fixated on the way they cover all but her head with surgical linen that they staple along her hairline. I asked Dr. Esra throughout about everything she had done when she couldn’t talk and for more on what the neurosurgeons were doing, which she did enthusiastically, giving me the elementary science behind their actions. I stay for about an hour and a half, but Dr. Esra recommends I go to some other ORs as this procedure had yet an hour of “long, boring stuff.”

I bid her adieu and went on my rounds. Stopping by OR 7, I stay surprisingly long while talking to anesthesiology resident Dr. Geesman about how he balances his studies nearing the end of his residency with his increased independence in the OR. Though a resident, he is the primary anesthesiologist (monitored by Dr. Teefs) for the 6-year-old from Latin America who came in with abdominal pain a week ago, got a CAT scan, and was revealed to have a mucousy liver. I watch the liver imaging (healthy liver is a consistent grey, the kid’s had black holes) as the IR (Interventional Radiology) doctor does a “minimally invasive” core biopsy to send to the pathologist. Off-hand, they predict that the kid has a kind of liver cancer that tends to be benign, a silver lining.

After that, I stop by a few other ORs and witness the first few minutes of an umbilical hernia process, but have to go back to OR 8 as they’d already cleaned up. I walk in as Dr. Esra’s second patient is set to come in. Same as the first, we go straight to holding to pick he rup and Dr. Esra explains the situation as we walk: this would be a nueropace implantation procedure – a full-fledged neurosurgery! However, my time is almost up – I go to the CAT scan with the team but must leave as Dr. Oluigo and his crew suit up again. My heart sinks but is immediately picked up when I recall just how much I learned – I knew a lot about the operating room and medical path, but I can’t even begin to explain how little I truly understood until I was there in person.

Uplifted, I go home to see Mom (right). Thrilled to see me dressed in scrubs like hers, she and all our house guests (she was hosting brunch for her church friends) call me “Dr. Ebey,” as expected.

Though it was once an irritating title that I felt limited my potential, I, for the first time, confidently think the same.

Mini- Reflection

I’m so excited that you’ve chosen to read my mission-affirming accounts in the OR! I realize now just how long this series will be – if anyone would like to see the other accounts, leave me a comment, and I’ll get on it.

My conclusions will still be released this Saturday. (My final judgments will be split between this section and “Developing a Congent, Linear Roadmap for Pursuing Medicine” – coming soon)